Cocaine-induced rhabdomyolysis with secondary acute renal failure

Images

Cocaine induced rhabdomyolysis with secondary acute renal failure

Findings

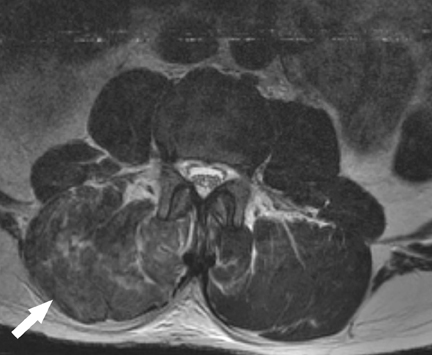

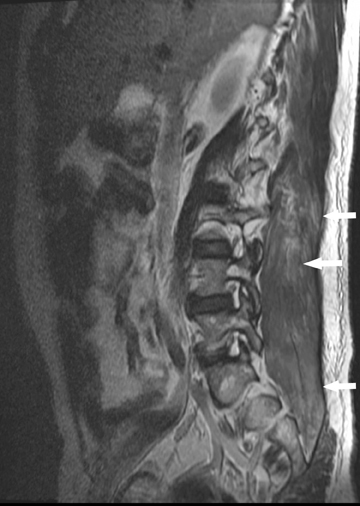

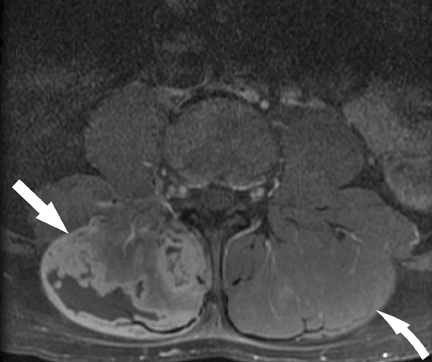

The MRI scan (Figure 1) revealed diffusely abnormal high signal on T2-weighted images with corresponding low signal on the T1-weighted sequences in the perispinal muscles. The muscle architecture was altered, and there was blurring of the margins between muscle bundles and an unsharp appearance to the contents of each muscle bundle. Small areas of confluent necrosis were also appreciated on the right (Figure 1). There was also abnormal enhancement diffusely in these muscles on postcontrast imaging (Figures 1). The other muscles were within normal limits.

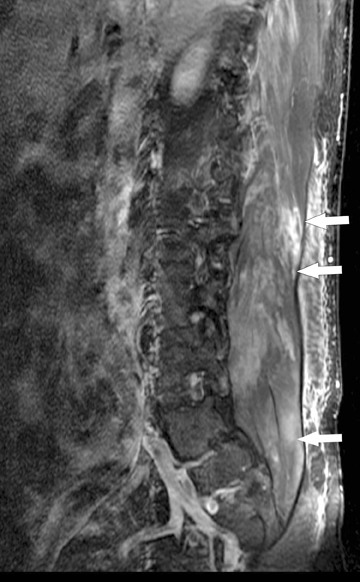

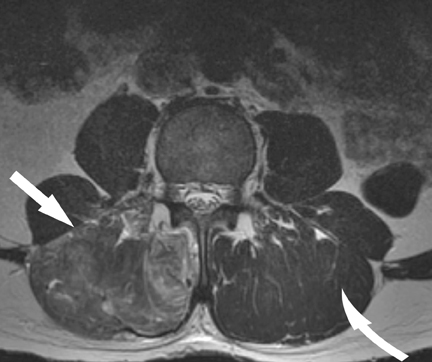

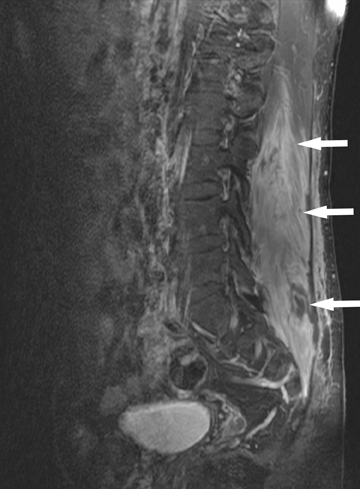

A follow-up MRI obtained one week later showed persistent signal abnormality (Figures 2); however, new areas of curvilinear T1 high signal appeared in the muscle, representing hemorrhage with loss of muscle architecture and more prominent areas of confluent necrosis. Enhancement was again seen and was only slightly decreased in prominence compared to the preceding study and the areas of confluent necrosis were clearly delineated (Figure 2). The abnormal signal in the left muscle complex had slightly improved in the interval.

Discussion

Rhabdomyolysis is an unusual entity induced by various etiologies. Recreational use of cocaine is one of the inciting factors for this condition. The incidence of rhabdomyolysis in patients who use cocaine varies from 5% to 30% in published reports. It is unclear why cocaine causes rhabdomyolysis. Hypotheses include cocaine-induced vasospasm with resultant muscle ischemia, excessive energy demands placed on the sarcolemma, and direct toxic effects on myocytes. Seizures, agitation, trauma, and hyperpyrexia may also play a role. In general, the severity of the rhabdomyolysis parallels the severity of the cocaine intoxication; patients with very high CK levels tend to have the most severe complications from this disease. Intravenous cocaine use may be associated with a higher incidence of rhabdomyolysis-induced acute renal failure (ARF) compared with smoking cocaine.1

Patients with rhabdomyolysis classically present with complaints of muscle weakness, swelling, and pain. The myalgias may be focal or diffuse, depending on the underlying cause of the disease. The patient may also note dark- or tea-colored urine. However, a high clinical suspicion for rhabdomyolysis must be maintained in patients at risk because up to 50% of those with serologically proven rhabdomyolysis do not report myalgias or muscle weakness.1

Rhabdomyolysis can induce ARF, particularly in hypovolemic or acidotic individuals. Myoglobinuric ARF complicates approximately 30% of cases of rhabdomyolysis. Common causes of the latter include traumatic crush injury, acute muscle ischemia, seizures, excessive exercise, heat stroke or malignant hyperthermia, intoxications (eg, alcohol, cocaine), and infectious or metabolic disorders.2-7 Compartment syndromes may be a cause or a complication of rhabdomyolysis.1,2

Early recognition of this condition is necessary for initiation of appropriate therapeutic measures. MRI findings of rhabdomyolysis include early onset of edema-like changes with increased T2- signal intensity. In the later phases, imaging demonstrates evidence of muscle fiber destruction manifested as loss of normal architecture, areas of necrosis and cavitation, abnormally elevated T1 signal representing hemorrhage, and abnormal enhancement. Some of these findings are difficult to differentiate from other causes of myonecrosis, which include sickle cell crisis, crush injuries, diabetic myonecrosis, compartment syndrome, and severe ischemia. Infection with abscess formation also presents with similar features. Some of these conditions have features that can help in differentiating them from rhabdomyolysis, such as involvement of the subcutaneous soft tissue and fat in crush injury, while others may present similar to rhabdomyolysis.8-11 Eliciting a good history usually provides a clue to the underlying etiology. However, as described above, some of these conditions may occur in tandem; for example, sickle cell crises may lead to myonecrosis with subsequent compartment syndrome and rhabdomyolysis. In general, severity of the signal intensity alterations correlates with severity of injury.3

Conclusion

Rhabdomyolysis should be entertained in the sudden onset of muscle pain and/or acute renal failure, especially in the setting of cocaine use, severe exertion, and trauma. MRI findings are helpful in determining the presence of this entity, which can be confirmed by testing the serum for elevated CK levels. It is important to remember that up to 50% of cases may be silent, without accompanying pain or muscle weakness, and the MRI findings may be the only suggestion of rhabdomyolysis.1 Early diagnosis allows the institution to provide appropriate management, given the frequency of acute renal failure in such patients.

- Botempo LJ. Rhabdomyolysis. In: Marx J, Walls R, Hockberger R, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 6th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Mosby Elsevier; 2006:chap 125.

- Brady HR, Brenner BM. Acute renal failure. In: Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Hauser S, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 16th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division; 2006:chap 260.

- Abraham B. Malignant hyperthermia susceptibility: Anaesthetic implications and risk stratification. QJM. 1997;90:13-18.

- Singhal PC, Rubin RB, Peters A, et al. Rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure associated with cocaine abuse. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1990;28:321-330.

- Welch RD, Todd K, Krause GS. Incidence of cocaine-associated rhabdomyolysis. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20:154-157.

- Roth D, Alarcon, FJ, Fernandez JA, et al. Acute rhabdomyolysis associated with cocaine intoxication. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:673-677.

- Counselman FL, McLaughlin, EW, Kardon, EM, Bhambhani-Bhavnani, AS. Creatine phosphokinase elevation in patients presenting to the emergency department with cocaine-related complaints. Am J Emerg Med. 1997;15:221.

- May DA, Disler DG, Jones, EA, et al. Abnormal signal intensity in skeletal muscle at MR imaging: Patterns, pearls, and pitfalls. Radiographics. 2000;20:S295–S315.

- Kakuda W, Naritomi, H, Miyashita, K, Kinugawa, H. Rhabdomyolysis lesions showing magnetic resonance contrast enhancement. J Neuroimaging. 1999;9:182-184.

- Stock KW, Helwig A. MRI of acute exertional rhabdomyolysis--in the paraspinal compartment. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1996;20:834-836.

- Lamminen AE, Hekali, PE, Tiula, E, et al. Acute rhabdomyolysis: evaluation with magnetic resonance imaging compared with computed tomography and ultrasonography. Br J Radiol. 1989;62:326-330.