Septic pelvic thrombophlebitis

Images

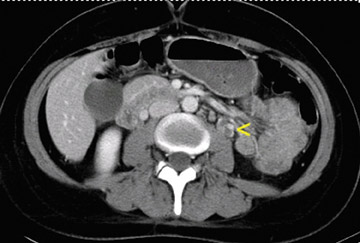

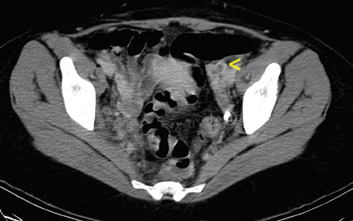

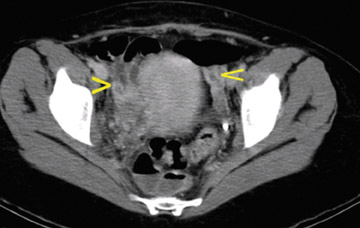

Axial computed tomography (CT) scans of the abdomen (Figure 1) and pelvis (Figure 2) were obtained following the administration of intravenous contrast. CT revealed a left ovarian vein filling defect, which extended into the pelvis with multiple filling defects in the left and right ovarian veins. The veins were edematous and tortuous as well as enlarged. No enhancing fluid collections were seen. The rest of the abdomen and the lung bases were unremarkable.

Discussion

Septic pelvic thrombophlebits is a rare complication of normal vaginal delivery.1 The incidence of septic pelvic thrombophlebitis has been reported to be between 1 in 600 to 1 in 2000 deliveries.2 There is a markedly higher incidence after Cesarean section than after vaginal delivery.3 In the face of endometritis after delivery, rates as high as 2% have been reported.3 The most common presenting symptoms include fever and abdominal pain. The abdominal pain is variable in presentation and may also involve the flank or back. Approximately half of cases also present with an abdominal mass.3 Any postpartum or postoperative patient who continues to spike a fever despite antimicrobial therapy should raise suspicion for this condition.3

This entity usually becomes apparent in the first week after delivery. Predisposing factors for pelvic thrombosis include venous stasis after childbirth, increased circulation of clotting factors during pregnancy, and vascular damage.4 Even in the absence of surgery, the pregnant patient is at increased risk for thrombosis. Thrombosis of the right ovarian vein is more common. This is believed to be, in part, caused by the dextrotorsion of the enlarging uterus that commonly occurs during pregnancy. This causes compression of the right ovarian vein and right ureter as they cross the pelvic rim. The right ovarian vein is also longer than the left ovarian vein and has many valves within its length. These valves may act as a nidus for thrombosis formation.

If left untreated, ovarian vein thrombophlebitis may extend into the renal veins or the inferior vena cava and can result in a pulmonary embolism.2 The diagnosis is most commonly made with contrast-enhanced CT, but CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are equally sensitive for detecting this disorder, and both are more sensitive than ultrasound.4 Treatment with antibiotics alone may lead to a spiking fever, which is often refractory to antibiotic therapy.2 Failure to recognize this condition may lead to surgical intervention and, even then, the condition may not be recognized.2 The diagnosis of ovarian vein thrombosis is often made only by exclusion.

With unenhanced CT imaging, an ovarian or iliac thrombosis appears as a hyperdense mass or isodense thrombus in the lumen of an enlarged vessel. With the infusion of intravenous contrast, a hypodense filling defect is seen within an enlarged vein, and there may be a variable amount of venous wall enhancement.4 There is often perivascular edema and venous tortuosity. On MRI, the venous thrombus may appear as a hyperintense filling defect on T1-weighted images and may appear isointense to hypointense to the surrounding blood on T2-weighted images. The lack of filling of a large, tortuous puerperal ovarian vein can be seen on 2- or 3-dimensional time-of-flight MR venography.4

CT has been shown to be comparable to MRI for detection of this entity; ultrasound has the lowest sensitivity rate.1 CT and MRI also better depict the anatomic extent of the thrombus. Overall, a combination of persistent fever with the typical CT or MRI appearance of thrombosis is a reasonable method of confirming the diagnosis.5

Treatment for this disorder is now almost exclusively medical and consists of intravenous heparin in combination with an adequate antibiotic treatment regimen. The dose of heparin is adjusted to achieve adequate anticoagulation with partial thromboplastin times of 1.5 to 2 times the control value.2

Antibiotic therapy in combination with intravenous anticoagulation is usually continued until the patient is afebrile or clinically well for 48 hours. Anticoagulation with heparin is maintained for a total of 5 to 7 days of apyrexia.2 Conversion to oral anticoagulation is not usually recommended unless there are pulmonary emboli or extensions of clot into the iliac veins or the inferior vena cava. Surgical treatment is reserved for patients who do not respond to intravenous anticoagulation or whose condition deteriorates despite heparin therapy.

Conclusion

Septic pelvic thrombophlebitis is a rare complication of puerperal infection. It is a potentially life-threatening emergency. Cross-sectional imaging with CT and MRI provides valuable tools for the diagnosis of this entity.

- Jassal DS, Fjeldsted FH, Smith ER, Sharma S. A diagnostic dilemma of fever and back pain postpartum. Chest. 2001;120:1023-1024.

- Mead PB, Hager DW, Faro S. Protocols for Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Blackwell Publishing, Ltd; 2000:527-532.

- Brown CE, Stettler RW, Twickler DM, Cunningham FG. Puerperal septic pelvic thrombophelbitis: Incidence and response to heparin therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:143-148.

- Twickler DM, Setiawan AT, Evans RS, et al. Imaging of puerperal septic thrombophlebitis: Prospective comparison of MR imaging, CT, and sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:1039-1043. Comment in: AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:1396-1397.

- Jassal DS, Fjeldsted FH, Smith ER, Sharma S. A diagnostic dilemma of fever and back pain postpartum. Chest. 2001;120:1023-1024.