Legal considerations in mammography

Mammography is a unique subspecialty within radiology where medical malpractice considerations are guided by both tort common law as well as statute. The Mammography Quality Standards Act (“MQSA”) was passed by the United States (U.S.) Congress in 1992 and requires all certified mammography facilities to meet uniform quality standards.1,2 Among the requirements are the annual certification of mammographic facilities, minimum reading requirements for those practicing mammography and the requirement that patients receive specified communications from the mammographer. These requirements may be intimidating for mammographers concerned about malpractice liability. However, this concern can be reduced if one knows, understands and implements the MQSA and American College of Radiology (ACR) standards for breast imaging into their practices, as a prosecutor representing the plaintiff will certainly know them.

This article aims to help the reader better understand the medicolegal aspects of breast imaging and review steps to help in one’s daily practice of breast imaging to reduce malpractice risk. This “risk management” is better thought of as a vehicle to provide and enhance quality of patient care and provide uniform policies for patients. Ultimately, this should also reduce the likelihood of a medical malpractice liability and increase one’s ability to defend oneself if necessary. These suggestions for reducing one’s liabilities may exceed the standards; however, they are provided to help reduce malpractice liability.

Missed breast cancer — perception and reality

There are numerous misperceptions and misunderstandings of breast imaging liability. In the past, “the allegation that an error in the diagnosis of breast cancer has occurred was one of the more prevalent conditions precipitating medical malpractice lawsuits against all physicians.”3 Approximately 5% to 17% of breast cancers are missed on screening mammography,4,5 while 75% of missed cancers can be found on previous mammogram (retrospective analysis).6 Indeed, 5% to 15% of palpable breast cancers are not revealed on mammography.7 However, the perceived risk of malpractice incidence in 5 years is nearly four times higher than the actual prevalence.8,9

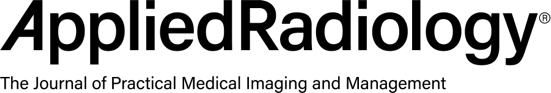

For a number of years, breast cancer was the number one cause of malpractice claims, and it is still among the top 5 errors in radiology claims.10 In the last 10 years, breast cancer case indemnity has significantly increased. There is also an incongruity between prevalence of breast cancer in different age groups and litigation compensation (Table 1). Almost 70% of breast imaging malpractice cases occur in women < 50 years of age, while the prevalence of breast cancer is < 25% in women under 509 and 78% of indemnity paid to women under 50. This is an often poorly understood trend that represents a significant amount of malpractice risk. Factors that contribute to this trend are the decreased sensitivity of mammography as breast density increases, the aggressive nature of breast malignancy in younger patients, and the likelihood that a jury will award a higher dollar amount to a younger female who may have a job and young children. The mammographer must be aware of these relationships.

Mitigating risk and providing high quality mammography

The radiologist must “sufficiently evaluate an abnormal mammographic finding.” One trial lawyer said appropriately, “you physicians practice great medicine, but you do not document this care.” An important consideration when treating patients is to document, document and document in the clinical report the quality of care provided to each patient, specifying what was done and why.

Before the exam

The first step in mammography begins before evaluation of images. One must first review the nonimaging data provided to the radiologist. This consists of 5 steps as illustrated in Table 2. In a malpractice suit, these steps represent areas where errors and ultimately malpractice can occur.

The second step is to obtain previous mammograms. One must make a reasonable effort to obtain prior mammograms, which is very necessary if significant findings are appreciated on the current exam. If unavailable, one should document the attempt to obtain prior mammograms and note, “will provide addendum if made available.” An effective method is to enlist the patient’s help by including the following statement in the patient’s report: “Please have the patient assist in obtaining prior mammograms as our attempts have failed. This may preclude the patient from having additional breast imaging and/or biopsies.” It is best that comparisons be made with previous studies dating back at least 2 years, as subtle findings, such as slower growing cancers and postsurgical breast changes are better appreciated.

The exam

Finally, there is the evaluation of the mammogram. Demand quality images! The radiologist is the one ultimately responsible for the quality of the study. If the images are of poor quality, ask for additional imaging and document this in the report. A suggested comment is: “The current study is inadequate due to [state the technical problem] and additional imaging [state the views] is needed at no expense to the patient.” Imaging a patient properly provides the highest quality care and will reduce one’s risk. Accordingly, mammographic masses and calcifications must be visualized and localized in different views. Reasonable attempts must be made to determine the exact location of a mass/Ca++ on 2 views. Different methods include: exaggerated craniocaudal (“CC”), roll medial or lateral CC, and tangential views.

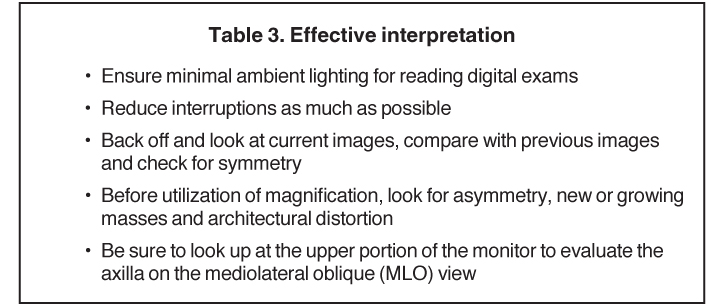

The radiologist must also ensure an adequate viewing environment and search pattern for reviewing mammograms as described in Table 3. It is important that as one accomplishes the steps outlined, one is sure to back off and look at the images. Many findings can be overlooked by not backing off and viewing the entire current and previous mammograms. One should do this prior to using the magnification device.

The report

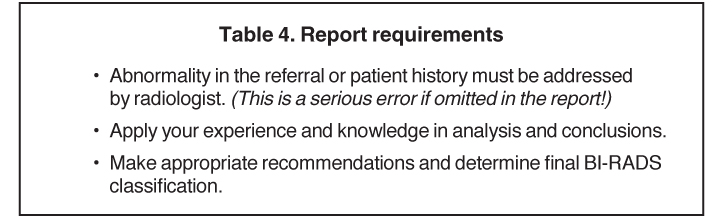

The quality of the exam report is as important as the interpretation of the examination itself, and the radiologist should assure that the report is clear and accurate. Typos and poorly written reports give a less than optimal impression to the clinician, patient, and members of the court. The effect of a sloppy report in court is extremely damaging. It cannot be emphasized enough—proofread your reports. The report should accomplish the 3 items summarized in Table 4. Radiologists are considered the most knowledgeable in mammography and breast imaging by the medical and legal communities. Deferring to “clinical correlation” does not excuse the radiologist from liability for any unreasonable interpretation or inadequate evaluation of an abnormal mammogram.

The screening exam of an asymptomatic patient will most commonly fall under BI-RADS categories 0, 1 or 2, and rarely BI-RADS 4 or 5. One should not utilize BI-RADS 3 for a screening exam, as these cases should be classified as BI-RADS 0, “additional imaging needed.” Of note, BI-RADS 1 or 2 results in the same patient disposition and recommendation for a follow-up screening exam in one year. A BI-RADS 2 (benign) is more easily defended than a BI-RADS 1 (negative) for a finding resulting in a medical malpractice case.

Similarly, the language of a screening exam that is placed in BI-RADS 0 is important for your colleagues who will be reading the follow-up diagnostic imaging. Use of language, such as “possible,” “questionable,” and “possible architectural distortion,” is suggested given the limited diagnostic scope of a screening exam. This allows some “wiggle room” for the mammographer reading the follow-up diagnostic mammogram when the questionable findings are not reproducible or are not real. It is suggested that the use of terms, such as “pleomorphic” or “spiculated,” in a screening exam classified as BI-RADS 0 be used cautiously, if at all. Keeping in mind that a screening exam is limited in sensitivity and specificity, there may be borderline findings. However, the final impression of a mammography report should always avoid ambiguity, which is different from an indeterminate assessment.

Communicating results

A learned judge stated that “the finding of a suspicious lesion raises the standard of care to a level whereby direct communication with the referring physician—beyond the issuing of the report—is required.” Another court has found that “the communication of a diagnosis so that it may be beneficially utilized may be altogether as important as the diagnosis itself.”10 These common law legal precedents inform the radiologist’s duties under the MQSA and ACR standards:

When there are ‘suspicious’ or ‘highly suggestive of malignancy’ results, the facility must also make reasonable attempts to communicate the results to the referring health care provider or a responsible designee as soon as possible.11,12

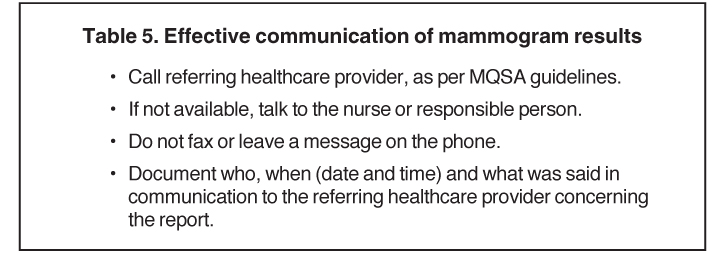

Communications should be high quality and verifiable. Recommendations are summarized in Table 5. Communications that are not effective and have results in settled cases include the generic, “A voice mail message was left for Dr. [Name] the referring physician concerning [Findings] on [date].”13

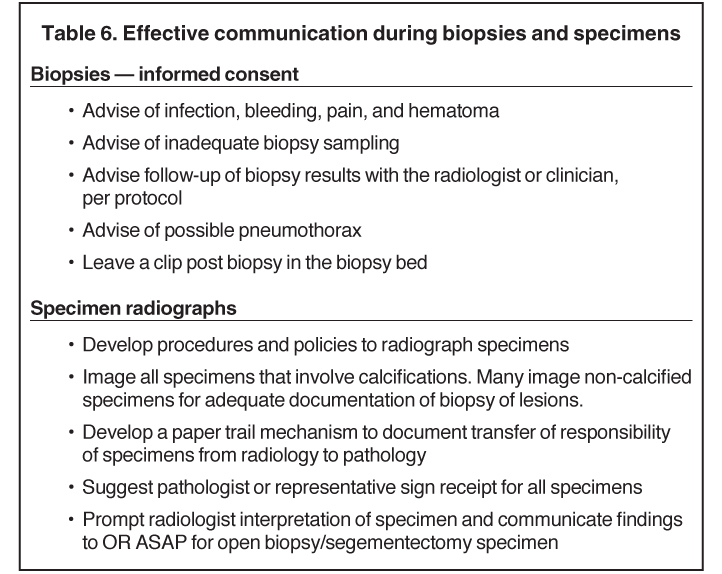

The mammographic results are not only limited to radiologist-referrer communications. On the contrary, they occur along the entire health care system. Some areas that one should also pay close attention to are the handling of and reading of specimen radiographs as well as biopsy procedures. An area of risk that is often overlooked is specimen handling. The loss of a specimen can be catastrophic, and the implementation of an effective chain of custody system is critical to mitigating risk. A document that proves a specimen was received by another department (eg: pathology) will prove critical in court. Additionally, appropriate informed consent is an important communication before any procedure and can be more effective with the use of a standardized form. Table 6 summarizes our recommendations.

Documentation

The complete and accurate role of documentation cannot be overemphasized. Take an extra moment to ensure a complete and accurate report, the communication with the patient and/or referring health care provider and the appropriate recommendations. What is written cannot be changed by another person, and what is not written is open for interpretation, usually different, by an opposing party. The extra minute to document may save years of legal action and a great sum of money.

Conclusion

There are a number of legal considerations in mammography. Beginning with the statistics of malpractice claims, the majority of litigation and claims occur in women younger than 50. This relationship is multifactorial and important for the radiologist to appreciate. Mammography in patients younger than 50 poses heightened malpractice risks, which should be addressed by risk mitigation strategies and high-quality mammography. These risk-mitigation strategies begin from the first patient encounter through the evaluation of past images, interpretation of current images, and effective communication to the patient and clinicians. A number of strategies and practice methods were reviewed to decrease the risk of making errors, becoming the target of malpractice litigation and making errors that appear unfavorable in a trial. There are more areas to explore that are outside the scope and limitations of this article. The topic of peer review and its role in litigation, effectively handling errors, and future modalities within breast imaging and their impact on litigation are additional areas of discussion. Finally, it is important to go above and beyond when documenting your best practices in breast imaging.

References

- Mammography Quality Standards Act Regulations, 42 U.S.C. 263 (b).

- 2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Mammography Quality Standards Act and Program. http://www.fda.gov/radiation-emittingproducts/mammographyqualitystandardsactandprogram. Accessed Nov 19, 2012.

- Practice standards claims survey. Physician Insurers Association of America and American College of Radiology. Rockville, MD: Physician Insurers Association of America, 1997.

- Majid AS, de Paredes ES, Doherty RD, et al. Missed breast carcinoma: Pitfalls and pearls. Radiographics. 2003;23:881-895.

- Buist DS, Porter PL, Lehman C, et al. Factors contributing to mammography failure in women aged 40-49 years. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1432-1440.

- Berlin L. Dot size, lead time, fallibility, and impact on survival: Continuing controversies in mammography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:1123-1130.

- Barlow WE, Lehman CD, Zheng Y, et al. Performance of diagnostic mammography for women with signs or symptoms of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1151-1159.

- Dick JF 3rd, Gallagher TH, Brenner RJ, et al. Predictors of radiologists perceived risk of malpractice lawsuits in breast imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:327-333.

- Howlader N. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2009 (Vintage 2009 Populations), National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09/, based on November 2011 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2012.

- Phillips v Good Samaritan Hospital, 416 NE2d 646 (Ohio App 1979).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Mammography Quality Standards Act of 1992: Policy guidance help system (updated December 1, 2010). http://www.fda.gov/Radiation-EmittingProducts/MammographyQualityStandardsActandProgram/Guidance/PolicyGuidanceHelpSystem/default.htm. Accessed Nov 19, 2012.

- Mammography Quality Standards Act Regulations, 21 CFR Part 900.12(c)(2)(i),(ii).

- Katz HP, Kaltsounis D, Halloran L, Mondor M. Patient safety and telephone medicine: Some lessons from closed claim case review. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:517-522.

- Physician Insurers Association of America and American College of Radiology. Practice standards claims survey. Rockville, MD: Physician Insurers Association of America, 1985-2009.