Ultrasound imaging of liver and renal transplantation

Images

Dr. Piyasena is a 4th-year Radiology Resident and Dr. Allison is the Director of the Radiology Residency Program and the Director of Ultrasound, Department of Radiology, Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC.

Prolonged graft survival as a result of improvements in surgical techniques and immunosuppressive drugs has led to an increased number of organ transplantation surgeries. Data from the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network shows that 16,481 kidney and 6443 liver transplants were performed in the United States in 2006 alone.1 Given this development, there is an increased need for accurate methods of evaluating suspected postoperative complications. Several of the major complications after liver and renal transplantation can rapidly lead to graft loss or further patient morbidity or mortality.

Most complications can be detected by ultrasound imaging, thus often making ultrasound the first-line method of diagnosis. Ultrasound is often the modality of choice for primary evaluation, as it is noninvasive, relatively inexpensive, does not require intravenous contrast, can be obtained at the bedside, and can often rapidly and accurately depict many common complications, most notably those of vascular etiology. Computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and angiography are often reserved for cases in which ultrasound is inconclusive or the extent of a finding cannot be fully appreciated by ultrasound alone. It is essential that the radiologist is able to recognize these complications so that proper management, including further diagnostic workup or surgical/radiologic intervention, can ensue.

In this article, the basic postsurgical anatomy of liver and renal transplants is presented, as well as the sonographic appearance of several of the complications that can often be detected by ultrasound, with emphasis on vascular complications.

Liver transplant

Anatomy

Various surgical techniques have been developed to increase the number of available organs for transplantation, including the use of living donor transplants or split cadaveric organ transplants. Liver splitting involves the division of a donor cadaveric liver in order to transplant the left lateral segment into a small child and the extended right segment into a larger child or adult.2,3 The sonographer must know the type of procedure that was performed in order to correctly identify and assess the involved vasculature, particularly when variant or suboptimal anatomy is identified or when a premorbid condition necessitates alteration of the routine transplant procedure, as in the case of an interposition graft.

Basic whole-liver transplantation involves 1 biliary and 4 vascular anastomoses and routine cholecystectomy. The preferred biliary anastomosis is end-to-end from the donor common bile duct to the recipient common hepatic duct. However, if the recipient common hepatic duct is diseased, too short, or otherwise inadequate for anastomosis, a choledochojejunostomy or hepaticojejunostomy with a Roux-en-Y limb is constructed.

The hepatic arterial anastomosis is typically an end-to-end fish-mouth anastomosis where the donor common hepatic artery and splenic artery branch point or the origin of the celiac artery with an aortic Carrel patch (small portion of the adjacent aorta surrounding the celiac artery origin) is connected to the recipient right and left hepatic artery bifurcation or the proper hepatic– gastroduodenal artery bifurcation. If the recipient has a dual blood supply to the native liver (for example, a replaced right hepatic artery from the superior mesenteric artery), then the larger of the arterial inflow vessels is used in the anastomosis. When the donor liver has a replaced right hepatic artery, the donor celiac artery with the Carrel patch is harvested and an anastomosis is created between the re-placed right hepatic artery and the proximal stump of the donor splenic artery, thus essentially recreating a single origin for the hepatic arterial inflow.4 At times, it may be necessary to use a donor iliac artery interposition graft attached directly to the supraceliac or infrarenal aorta to ensure adequate arterial inflow as in the case of stenosis or small caliber of the more distal native artery.5

The portal vein anastomosis is also an end-to-end anastomosis. In the case of portal vein thrombosis or previous portal vein surgery, a donor iliac vein jump graft may be interposed between the recipient superior mesenteric vein or splenic vein and the donor portal vein.6

The donor inferior vena cava (IVC) is typically transected immediately above and below the intrahepatic portions and the supra- and infra-hepatic anastomoses are performed in an end-to-end fashion (Figure 1A). A variation of this procedure involves an end-to-side (piggyback technique) or side-to-side anastomosis, thereby leaving the recipient IVC intact (Figure 1B).7

Liver transplant complications

Complications after liver transplantation can be subdivided into vascular and nonvascular. For the purpose of this article, emphasis will be placed on vascular complications.

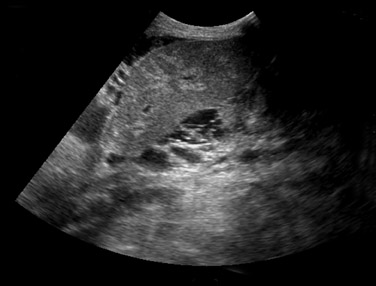

Nonvascular complications–– Small perihepatic fluid collections are common immediately after surgery and typically represent small hematomas or seromas. These collections should resolve within a few days or weeks after surgery. Although ultrasound is sensitive to the presence of perihepatic fluid, the specificity is very low. Many of the common fluid collections, including blood, pus, ascites, bile, or lymph, can all have a similar appearance (Figure 2). The differential diagnosis will depend on the specific appearance and timing of its development related to surgery. The significance of a perihepatic fluid collection often depends on the size of the collection (whether or not there is resultant mass effect) and the clinical setting.

Posttransplant liver parenchymal abnormalities may be focal or diffuse. Focal lesions may represent pre-existing donor disease (such as a hepatic cyst or hemangioma), infarct, abscess, biloma, or metastatic disease. Particular attention should be paid to the hepatic artery when a liver abscess or infarct is suspected, as they may be the result of hepatic arterial thrombosis or stenosis. Evaluation of the liver parenchyma may reveal recurrent hepatic disease, as has been well documented in cases of viral hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and malignancy, such as hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. Other diffuse parenchymal abnormalities include rejection, ischemia, hepatitis, or cholangitis, but these may show only nonspecific heterogeneity of the liver parenchyma. The hepatic artery resistive index has been shown to be unreliable in the assessment of transplant rejection.7-9

Posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) complicates 2% to 8.4% of adult liver transplants.10 This disease process can involve the lymph nodes, lungs, bowel, and abdominal organs. Extrahepatic disease appears as a poorly defined hypoechoic hilar mass, while intrahepatic disease may appear as a focal solid hypoechoic mass or a diffuse infiltrative parenchymal process11 (Figure 3).

Biliary complications are common and are seen in up to 25% of transplants.12 The vast majority of these complications are made up of biliary leaks. Bile leaks may occur at the T-tube insertion site after its removal several months after surgery, and at the anastomosis. Anastomotic strictures may result from scarring secondary to surgical manipulation and can result in intrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation. The native duct will often be normal in caliber. Nonanastomotic leaks and strictures are often the result of ischemia secondary to hepatic artery compromise.13 Intra- or extrahepatic bilomas can collect as a result of a bile leak, which can then become infected.14

Less common biliary complications include biliary sludge and stones. Generalized bile duct abnormalities in the absence of obstruction or leakage can be seen in cases of rejection, ischemia, or cholangitis.

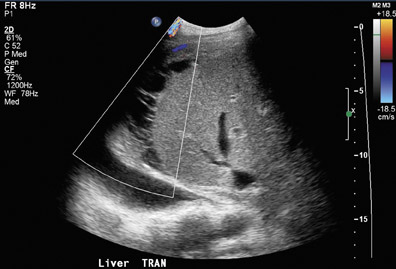

Hepatic vasculature—Vascular complications from liver transplantation can result in significant compromise to the graft, often in the early postoperative period.11 Gray-scale, color, and spectral Doppler is performed on all of the major vessels in order to exclude thrombosis or stenosis. The authors must emphasize the importance of knowing the exact postsurgical anatomy, as it is essential that all vascular anastomoses are evaluated. The majority of vascular complications occur at or adjacent to an anastomosis.

Hepatic artery thrombosis is the most common and most devastating vascular complication, accounting for 60% of all vascular complications and occurring in 4% to 12% of adult transplants.15,16 Hepatic artery thrombosis is the second leading cause of graft failure in the early postoperative period after acute rejection.7 Patients with hepatic arterial thrombosis may present with fulminant liver necrosis, bile leak due to bile duct necrosis, or relapsing bacteremia.17

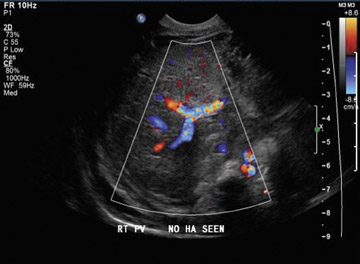

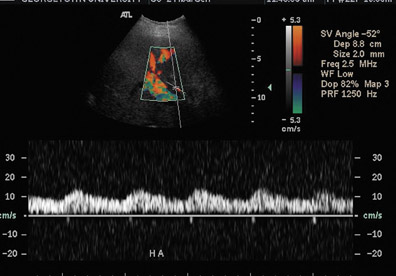

Ultrasound correctly identifies 92% of thrombosed hepatic arteries.18 Spectral Doppler evaluation of a thrombosed hepatic artery shows absent extra- and intrahepatic arterial flow (Figure 4). False-positive findings of hepatic artery thrombosis are often attributed to technical factors such as large patient size or marked ascites. Occasionally, the arterial flow may be below the level of detection for the ultrasound probe because of hepatic edema, systemic hypotension or proximal stenosis.5,19 In the acute postoperative period, impending thrombosis may present with a typical pattern of progression on serial Doppler examinations (Figure 4). Sonograms show normal hepatic arterial flow on day 1, then a progressive decrease of diastolic flow, followed by a dampening of systolic flow, and finally the total loss of the hepatic arterial waveform.7

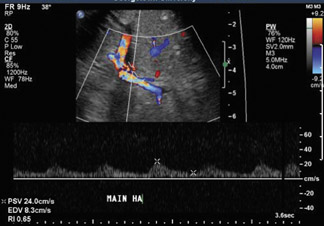

Hepatic artery stenosis has been reported to occur in 11% of orthotopic liver transplant patients, most often at the anastomotic site.19,20 Contributory factors may include faulty surgical technique, clamp injury, vessel ischemia due to disrupted vasa vasorum, or rejection. Doppler ultrasound of the hepatic artery in the region of the stenosis will show a focal increase in velocity greater than 2 to 3 m/sec with associated turbulence and spectral broadening distally (Figure 5A). Distal to the stenosis, a tardus-parvus waveform may be seen, consisting of a prolonged systolic acceleration time (>0.08 seconds) and a resistive index <0.5 (normal 0.5 to 0.7) (Figure 5B). If technical factors do not allow direct visualization of the hepatic artery anastomosis, a tardus-parvus pattern alone in the more distal hepatic artery is approximately 75% sensitive and specific for hepatic arterial stenosis.19

Less commonly, liver transplantation may be complicated by a pseudoaneurysm, most often mycotic and occurring at the anastomosis. An intrahepatic pseudoaneurysm may result from a focal infection or a percutaneous procedure. On ultrasound, the pseudoaneurysm typically appears as an intrahepatic or periportal cystic structure with disorganized turbulent flow along the course of the hepatic artery.7

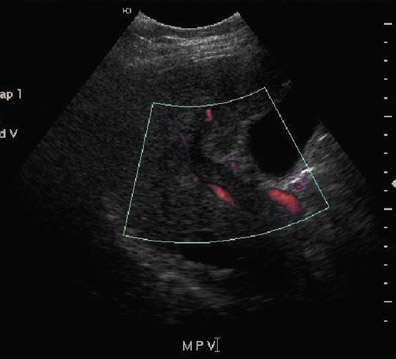

Portal vein thrombosis or stenosis is a less common complication, occurring in 1% to 2% of patients.15,20 Possible risk factors include faulty surgical technique, hypercoagulable states, vessel size discrepancies that lead to increased turbulence, excessive vessel length or previous portal vein surgery. Ultrasound of portal vein thrombosis may show an echogenic or hypoechoic intraluminal thrombus (Figure 6A) and an absence of Doppler flow (Figure 6B). A focal area of narrowing at the portal venous anastomosis may be normal, particularly in cases of size discrepancy between donor and recipient; however, a greater than 3- to 4-fold increase in velocity at the stenosis relative to the prestenotic segment is compatible with a significant stenosis.

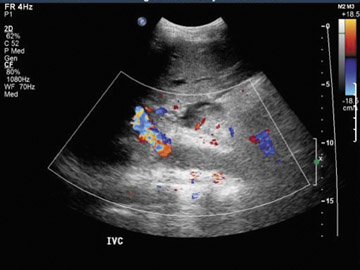

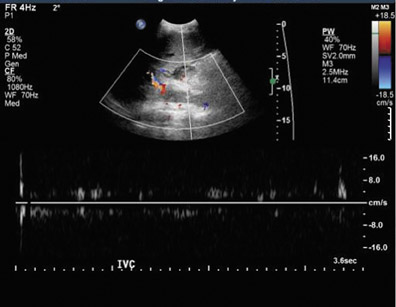

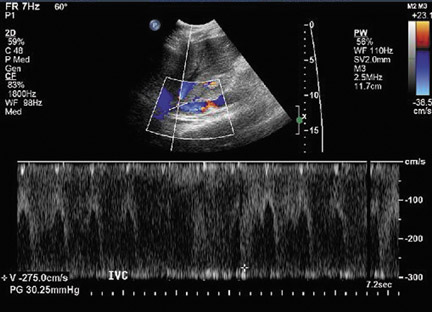

Inferior vena cava thrombosis and stenosis are the least common vascular complications (found in <1% of transplant cases)15,20 and more frequently involve the anastomosis.5 With gray-scale ultrasound, IVC thrombus appears as an intraluminal echogenic structure (Figure 7A). Absence of flow can be confirmed with color and spectral Doppler imaging (Figure 7B). Inferior vena cava stenosis may show a focal narrowing of the IVC with color aliasing on Doppler imaging (Figure 8A) that should be differentiated from potential donor-recipient size discrepancy. A greater than 3- or 4-fold velocity increase at the stenosis relative to the prestenotic IVC is considered significant (Figure 8B and C). With IVC thrombosis or severe stenosis, there may be a reversal of flow of the hepatic veins and a loss of the normal phasicity of the venous waveforms of the hepatic veins and IVC proximal to the thrombosis/stenosis7 (Figure 8D).

Renal transplant

Anatomy

The transplanted kidney is usually placed in an extraperitoneal location in the right or left iliac fossa. Kidney transplants are identified by the source of the donor organ, including a cadaveric renal transplant (CRT) (with the donor organ from a cadaver), a “living” renal transplant (LRT) (with the donor organ from a living relative) or a living nonrelative renal transplant (LNRT) (with the donor organ from a living nonrelated person). With CRT, a Carrel patch (a small portion of surrounding aorta) is acquired and anastomosed to the recipient external iliac artery in an end-to-side fashion. Both LRT and LNRT procedures often involve an end-to-side anastomosis of the donor renal artery to the recipient external iliac artery or an end-to-end anastomosis of the donor renal artery to the recipient internal iliac artery. Variant anatomy with multiple renal arteries can be anastomosed separately to the external iliac artery or with a Carrel patch that encompasses all of the origins. Alternatively, the individual arteries can be anastomosed to the largest so that there is essentially a single donor vessel supplying the entire graft. The renal vein is attached in an end-to-side anastomosis to the external iliac vein. Ureteral drainage is restored, preferably by means of ureteroneocystostomy. Another procedure sometimes performed for kidneys obtained from donors <5 years of age involves the transplantation of both kidneys into a single recipient and using the donor aorta and vena cava for vascular anastomosis (an “en bloc” pediatric transplant). As with liver transplants, knowledge of the exact renal transplant procedure performed is essential for accurate interpretation of both normal and abnormal findings.

Renal transplant complications

Complications after renal transplantation can also be subdivided into vascular and nonvascular complications.

Nonvascular complications—Perinephric fluid collections are a common occurrence, found in up to 50% of renal transplants.21 These include urinomas, hematomas, seromas, lymphoceles, and abscesses. Although ultrasound is sensitive for their detection, the sonographic appearance of collections can overlap. The clinical relevance of a fluid collection depends on its composition, size, location, and whether or not it is getting larger or exerting significant mass effect.

The differential diagnosis can be narrowed based on the time of presentation. Urinomas and hematomas often present in the immediate postoperative period (up to 2 weeks after surgery), with hematomas evolving in appearance over time. Lymphoceles are usually delayed, occurring 4 to 8 weeks after surgery. Unless infected or mixed with blood, urinomas appear as well-defined anechoic collections without septations. Perinephric abscesses are uncommon but can occur in the early postoperative period and are caused by pyelonephritis or bacterial seeding of a urinoma, hematoma, or lymphocele. The clinical presentation plays a significant role in establishing the diagnosis.

Renal parenchymal abnormalities can be divided into focal or diffuse processes. A focal area of increased or decreased echogenicity may represent focal pyelonephritis, infarct, or rejection (Figure 9).

Posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder complicates approximately 1% of renal transplant patients, with a spectrum of disease ranging from mild diffuse polyclonal lymphadenopathy to malignant monoclonal lymphoma.22 The following can be involved in PTLD: any of the solid organs; hollow viscera; abdominal, retroperitoneal, and iliac lymph nodes; retroperitoneal musculature; or peritoneum of the abdomen, with the extranodal disease predominating. Involvement of the transplant kidney appears as single or multiple hypo- or mixed echogenic masses.

The sonographic appearances of many diffuse renal parenchymal abnormalities are nonspecific. Diffuse renal enlargement, cortical thickening, increased or decreased cortical echogenicity, loss of corticomedullary differentiation, prominent pyramids, and thickening of the collecting system can all be seen in the setting of diminished renal function. Although elevated resistive index obtained at the arcuate arteries was previously described as an accurate method of detecting acute rejection,23 it has been subsequently shown that increases in the resistive index can be seen in various other conditions, including acute tubular necrosis, renal vein thrombosis, graft infection, compressive perinephric fluid collections, and obstructive hydronephrosis.24 An elevated resistive index (>0.8) is now used as a nonspecific parameter of renal dysfunction (Figure 10). Ultimate differentiation between acute tubular necrosis (acute vasogenic nephropathy), acute or chronic rejection, or drug nephrotoxicity requires a biopsy.

Urologic complications occur in 4% to 8% of patients, including urine leak/ urinoma, urinary obstruction, and urinary calculi.25 Urine leaks and urinomas often occur in the early postoperative period; the patient usually presents with pain and swelling at the surgical site and drainage from the wound. Urinomas appear as nonspecific, well-defined anechoic collections without septations.

Urinary tract obstruction occurs in approximately 2% of renal transplants, most often during the first 6 postoperative months. More than 90% occur at the distal third of the ureter, most commonly at the ureterovesicle junction.26 Causes of obstruction include edema at the anastomosis, ischemia or rejection leading to fibrosis and stenosis, technical error during the ureteroneocystostomy, and kinking of the ureter. Other, less common causes include calculi, papillary necrosis, fungus ball, hematoma, and extrinsic compression by perinephric fluid.

The patient with urinary obstruction may not complain of typical renal colic, as the transplant kidney is denervated. Additionally, this denervation prevents the transplanted kidney from maintaining any intrinsic tone, often resulting in a persistent appearance of mild dilatation. It should also be noted that edema and fibrosis associated with rejection may prevent the normal dilatation seen with hydronephrosis.27 Thus, the clinical setting and the use of further imaging (eg, diuretic renography) may be necessary to determine the functional significance of the appearance of a dilated collecting system. Secondary infection or pyonephrosis should be suspected when complex-appearing urine is detected in a dilated collecting system (Figure 11).

Renal transplant recipients are at increased risk for developing renal calculi.28 Renal stones typically appear as echogenic, strongly shadowing structures in the collecting system. Fungus balls should be suspected when a highly echogenic mass in the transplanted collecting system exhibits weak shadowing.

Renal vasculature—Vascular complications occur in 1% to 10% of patients.25,29 Renal artery thrombosis is a devastating complication and often leads to graft loss. Doppler ultrasound shows absent intrarenal arterial or venous flow. It should be noted that markedly diminished blood flow can be seen in severe rejection and may not be detected on color Doppler.30

Renal vein thrombosis is an early complication that can be secondary to surgical technique, compression of the renal vein by a fluid collection, or hypovolemia. The kidney may appear enlarged and hypoechoic with a lack of Doppler signal in the renal vein. The renal artery shows increased resistance, often with reversed, plateauing diastolic flow31 (Figure 12). Reversal of diastolic flow can also be seen in the setting of severe rejection or acute tubular necrosis, but the additional finding of absent venous flow is essentially diagnostic for renal vein thrombosis.

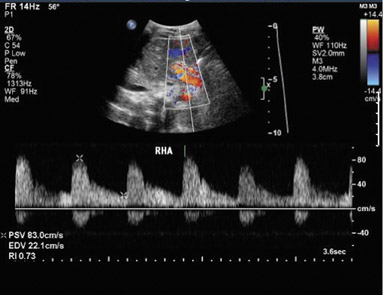

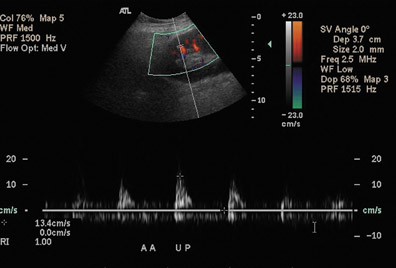

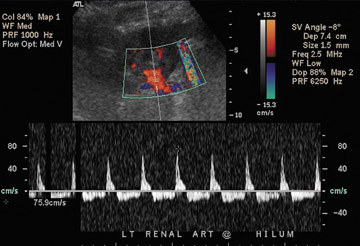

Renal artery stenosis usually occurs during the first year after surgery and is the most common vascular complication of renal transplantation. Approximately half of stenoses occur at the anastomosis due to perfusion cannula injury, faulty suture technique, or reaction to suture material, with end-to-end anastomoses having a higher risk of stenosis. Stenosis can occur proximal to the anastomosis (often due to atherosclerotic disease) or distal to the anastomosis, secondary to rejection or turbulent flow. Doppler ultrasound will show a focal area of color aliasing with velocities >2 m/sec, a velocity gradient between the stenotic and prestenotic segment of more than 2:1, and poststenotic spectral broadening (Figure 13A). A tardus-parvus waveform may be observed in the renal parenchyma32 (Figure 13B).

Renal vein stenosis is less common and usually results from extrinsic compression by fluid collections or perivascular fibrosis. A focal aliasing with a 3- to 4-fold increase in velocity on color Doppler imaging indicates a significant stenosis.33

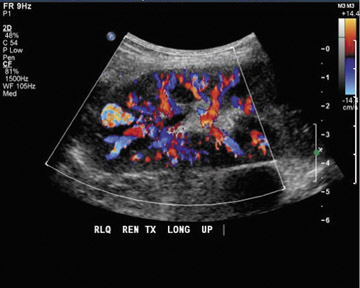

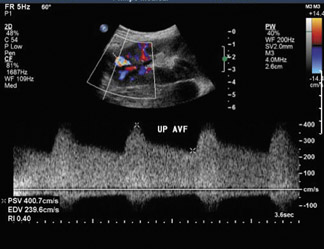

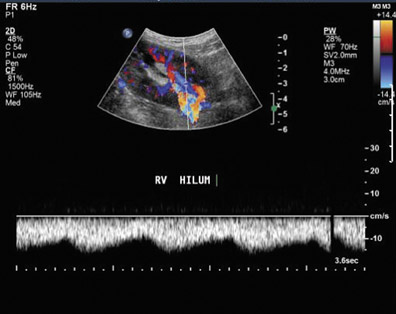

Arteriovenous fistulas and pseudoaneurysms may result from percutaneous biopsy of the transplant kidney. Most of these lesions are small and clinically insignificant; however, large shunts may lead to renal ischemia, and rupture of large arteriovenous fistulas and pseudoaneurysms can cause hematuria or perigraft hemorrhage. Gray-scale ultrasound may show findings similar to simple or complex renal cysts, but with color Doppler, intense, disorganized flow is identified (Figure 14A). Larger arteriovenous fistulas may show a focal flurry of disorganized color flow thought to be caused by vibration of the tissue surrounding the fistula. The feeding artery will show a high-velocity, low-resistance waveform, and the draining vein may show pulsatile, arterialized flow34 (Figure 14). Pseudoaneurysms with a narrow neck show a “to-and-fro” waveform (forward and reverse flow in the neck). Pseudo-aneurysms can occur at vascular anastomoses or in association with infection.

Conclusion

Ultrasound is a useful tool in imaging both renal and hepatic transplants. Knowledge of the surgical anatomy and normal and abnormal appearances of the transplanted organ permits prompt recognition of complications.

REFERENCES

- United Network for Organ Sharing and Scientific Registry data. Data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Available at: http://www. unos.org. Accessed January 2007.

- Broelsch CE, Whitington PF, Emond JC, et al. Liver transplantation in children from living related donors. Surgical techniques and results. Ann Surg. 1991;214:428-437; discussion 437-439.

- Berrocal T, Parrón M, Alvarez-Luque A, et al. Pediatric liver transplantation: A pictorial essay of early and late complications. RadioGraphics. 2006;26: 1187-1209.

- Ishigami K, Zhang Y, Rayhill S, Katz D, Stolpen A. Does variant hepatic artery anatomy in a liver transplant recipient increase the risk of hepatic artery complications after? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1577-1584.

- Nghiem HV, Tran K, Winter TC III, et al. Imaging of complications in liver transplantation. RadioGraphics. 1996;16:825-840.

- Shaked A, Busuttil RW. Liver transplantation in patients with portal vein thrombosis and central portacaval shunts. Ann Surg. 1991;214:696-702.

- Crossin J, Muradali D, Wilson SR. US of liver transplants: Normal and abnormal. RadioGraphics. 2003;23:1093-1114.

- Stell D, Downey D, Marotta P, et al. Prospective evaluation of the role of quantitative Doppler ultrasound surveillance in liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:1183-1188.

- Marder DM, DeMarino GB, Sumkin JH, Sheahan DG. Liver transplant rejection: Value of the resistive index in Doppler US of hepatic arteries. Radiology. 1989;173:127-129.

- Strouse PJ, Platt JF, Francis IR, Bree RL. Tumorous intrahepatic lymphoproliferative disorder in transplanted livers. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167: 1159-1162.

- Wu L, Rappaport DC, Hanbidge A, et al. Lympho-proliferative disorders after liver transplantation: Imaging features. Abdom Imaging. 2001;26:200-206.

- Letourneau JG, Castañeda-Zuñiga WR. The role of radiology in the diagnosis and treatment of biliary complications after liver transplantation. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1990;13:278-282.

- Zajko AB, Campbell WL, Logsdon GA, et al. Cholangiographic findings in hepatic artery occlusion after liver transplantation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:485-489.

- Almusa O, Federle MP. Abdominal imaging and intervention in liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:184-193.

- Langnas AN, Marujo W, Stratta RJ. Vascular complications after orthotopic liver transplantation. Am J Surg. 1991;161:76-82.

- Nghiem HV. Imaging of hepatic transplantation. Radiol Clin North Am. 1998;36:429-443.

- Tzakis AG, Gordon RD, Shaw, Jr. BW, et al. Clinical presentation of hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation in the cyclosporine era. Transplantation. 1985;40:667-671.

- Flint EW, Sumkin JH, Zajko AB, Bowen A. Duplex sonography of hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;151: 481-483.

- Dodd GD III, Memel DS, Zajko AB, et al. Hepatic artery stenosis and thrombosis in transplant recipients: Doppler diagnosis with resistive index and systolic acceleration time. Radiology. 1994;192:657-661.

- Wozney P, Zajko A, Bron KM, et al. Vascular complications after liver transplantation: A 5-year experience. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;147:657-663.

- Silver TM, Campbell D, Wicks JD, et al. Peritransplant fluid collections. Ultrasound evaluation and clinical significance. Radiology. 1981;138:145-151.

- Vrachliotis TG, Vaswani KK, Davies EA, et al. CT findings in posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder of renal transplants. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:183-188.

- Rifkin MD, Needleman L, Pasto ME, et al. Evaluation of renal transplant rejection by duplex Doppler examination: Value of the resistive index. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148:759-762.

- Finlay DE, Letourneau JG, Longley DG. Assessment of vascular complications of renal, hepatic, and pancreatic transplantation. RadioGraphics. 1992;12: 981-996.

- Kocak T, Nane I, Ander H, et al. Urological and surgical complications in 362 consecutive living related donor kidney transplantations. Urol Int. 2004;72:252-256.

- Bennett LN, Voegeli DR, Crummy AB, et al. Urologic complications following renal transplantation: Role of interventional radiologic procedures. Radiology. 1986;160:531-536.

- Akbar SA, Jafri SZ, Amendola MA, et al. Complications of renal transplantation. RadioGraphics. 2005;25:1335-1356.

- Cho DK, Zackson DA, Cheigh J, et al. Urinary calculi in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1988;45:899-902.

- Jordan ML, Cook GT, Cardella CJ. Ten years of experience with vascular complications in renal transplantation. J Urol. 1982;128:689-692.

- Grenier N, Douws C, Morel D, et al. Detection of vascular complications in renal allografts with color Doppler flow imaging. Radiology. 1991;178:217-223.

- Kaveggia LP, Perrella RR, Grant EG, et al. Duplex Doppler sonography in renal allografts: The significance of reversed flow in diastole. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;155:295-298.

- Dodd GD III, Tublin ME, Shah A, Zajko AB. Imaging of vascular complications associated with renal transplantation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157: 449-459.

- Tublin ME, Dodd GD III. Sonography of renal transplantation. Radiol Clin North Am. 1995;33:447-459.

- Middleton WD, Kellman GM, Melson GL, Madrazo BL. Postbiopsy renal transplant arteriovenous fistulas: Color Doppler US characteristics. Radiology. 1989;171:253-257.

Related Articles

Citation

Ultrasound imaging of liver and renal transplantation. Appl Radiol.

April 3, 2008