Radiological Case: Intussusception

Images

CASE SUMMARY

A 3-month-old male infant presented initially to the emergency department with a 1-day history of fever, vomiting, cough, nasal congestion, and rapid breathing. He was discharged from the emergency department (ED) with a diagnosis of viral bronchiolitis after clinical improvement following treatment with azithromycin and steroids. A next-day follow-up examination by the child’s pediatrician revealed the patient’s respiratory symptoms had improved, but also revealed bright red blood in stool. The patient also had decreased urine output, refused breastfeeding, and had lost some weight. The patient was admitted with mild to moderate dehydration, and abdominal imaging was performed.

IMAGING FINDINGS

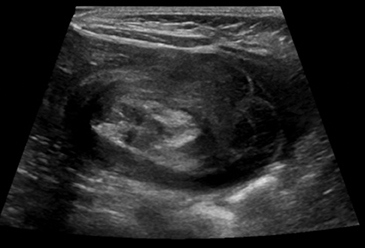

Plain film radiography of the abdomen demonstrated multiple dilated loops of small bowel suggestive of small bowel obstruction. The clinical picture and abdominal films suggestive of bowel obstruction combined to generate a concern for intussusception; therefore, an emergent ultrasound of the abdomen was performed.

The ultrasound revealed a targetoid appearance (Figure 1) in the bowel and a pseudokidney sign (Figure 2) consistent with intussusception. Immediately following the scan, a therapeutic contrast enema was administered multiple times in an attempt to reduce the intussusception but was unsuccessful. At this point, the patient was referred to a tertiary care center.

DIAGNOSIS

Intussusception

DISCUSSION

Intussusception describes the process by which one portion of bowel telescopes inside an adjacent portion of bowel, leading to intestinal obstruction and ultimately causing bowel necrosis due to vascular compromise.1,2 The most common location for this to occur is near the ileocecal junction.1,2 Intussusception most commonly occurs in children aged 6 to 36 months, with a slightly increased male-to-female ratio.1 There is also a strong association with adenovirus infection causing lymphadenopathy of the Peyer’s patches, which can cause a lead point for intussusception.3 A lead point is any abnormality of intestine that is relatively immovable and gets pushed by peristalsis into the lumen of adjacent intestine.1,2

Intussusception classically presents as sudden, intermittent, crampy abdominal pain that increases in frequency with time.1,2 Between periods of pain, the child is relatively pain free. A child will classically flex his hips when in pain.1,2 It often presents with gross or occult blood and/or mucous in the stool and possible vomiting.1,2 These symptoms are often confused with gastroenteritis.1,2 The differential diagnosis for intussusception includes gastritis, appendicitis, hernia, testicular torsion, and volvulus.1,2 In some cases, the patient may simply present with lethargy from profound dehydration; therefore, intussusception should always be in the differential for pediatric lethargy.1,2

The imaging workup for suspected intussusception includes plain film radiography, ultrasound, and contrast enema. Plain film abdominal radiographs have a sensitivity of 45% for detecting intussusception,4 but may be the initial study obtained during the workup. Lack of air in the cecum or a “meniscus sign” may be present on abdominal plain film, indicating intussusception (Figure 3).4 Because of its greater accuracy for detection of intussusception (sensitivity of 97.9% and specificity of 97.8%),5 lack of ionizing radiation, and its ability to rule out other potential pathologies on the differential, ultrasound is the current first-line modality for evaluating suspected intussusception.5 Contrast enema confirming an intussusception may also show a meniscus sign.6

Hydrostatic contrast or pneumatic enemas are very successful, non-operative options, and are the treatments of choice for reducing intussusception in stable patients by exerting pressure on the apical point of the intussusception.6 A complication of enema reduction is bowel perforation from excess pressure on damaged or gangrenous bowel. Keeping the enema bag height at or below 3.5 feet from the patient’s table reduces the chances for perforation.6 For pneumatic enemas, the risk is higher, in general due to fluctuating pressures throughout the colon associated with this procedure versus the relatively constant pressure of hydrostatic enemas. For this reason, pneumatic enema pressure is measured via manometer and kept at or below 120 mmHg to avoid perforation.6

CONCLUSION

The initial imaging of children with suspected intussusception should be performed with abdominal ultrasound.

REFERENCES

- Marinis A, Yiallourou A, Samanides L, et al. Intussusception of the bowel in adults: A review. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:407-411.

- Slovis T L. Caffey’s Pediatric Diagnostic Imaging. Mosby Elsevier. 2008;2: 2177-2186.

- Bines JE, Liem NT, Justice FA, et al. Risk factors for intussusception in infants in Vietnam and Australia: Adenovirus implicated, but not rotavirus. 2006;149:452-460.

- Ko HS, Schenk JP, Troger J, Rohrschneider WK. Current radiological management of intussusception in children. Eur Radiol. 2007;17(9):2411-21. Epub 2007 Feb 17.

- Bines JE, Liem NT, Justice F, et al. Validation of US as a first-line diagnostic test for assessment of pediatric ileocolic intussusception. Ped Radiol. 2009;39(10):1075-1079.

- Del-Pozo G, , Albillos J, Tejedor D, et al. Intussusception in children: Current concepts in diagnosis and enema reduction. Radiographics. 1999;19(2):299-319.

Citation

Radiological Case: Intussusception. Appl Radiol.

September 5, 2014