Superior Mesenteric Artery Compression Syndrome

Images

CASE SUMMARY

A 20-year-old male with acute lymphoblastic leukemia presented with fever, nausea and abdominal pain. A review of systems revealed recent weight loss with a further 8-kg weight loss during the current admission.

IMAGING FINDINGS

Initial CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with intravenous contrast demonstrated fluid-filled loops of small bowel suggestive of gastroenteritis. Additional findings included dilation of the first and second portions of the duodenum with narrowing and small caliber of the third portion as it crosses the midline posterior to the superior mesenteric artery (SMA, Figure 1) and decreased aortomesenteric angle (Figure 2).

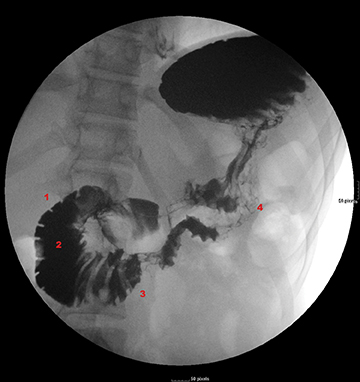

A barium upper gastrointestinal study was ordered to confirm superior mesenteric artery compression syndrome as suggested by the CT findings. If confirmed, this would account for the patient’s nausea and abdominal pain. The upper GI study revealed a dilated first and second portion of the duodenum with abrupt linear vertically oriented cutoff of contrast at the junction of the second and third portions of the duodenum (Figure 3). Upon repositioning, there was subsequent contrast transit to the small-caliber third and fourth portions of the duodenum (Figure 4). Findings were diagnostic of SMA compression syndrome.

DIAGNOSIS

Superior mesenteric artery compression syndrome. The differential diagnosis includes duodenal stricture, intestinal scleroderma, annular pancreas, and median arcuate ligament syndrome.

DISCUSSION

Superior mesenteric artery compression syndrome, also known as Wilkie’s syndrome, duodenal vascular compression syndrome,cast syndrome, or arteriomesenteric duodenal compression syndrome,1,2,3 is clinically manifested as postprandial epigastric pain and/or fullness accompanied by nausea, vomiting and weight loss.1 The epigastric pain is characteristically relieved by repositioning, often in the left lateral decubitus or prone positions. This condition is often seen in patients with rapid or severe weight loss such as patients with prolonged immobilization, severe burns, anorexia nervosa, severe weight loss, or spinal cord injury,2 leading to loss of retroperitoneal fat, which normally cushions the superior mesenteric artery from the posteroinferior third segment of the duodenum.2 The retroperitoneal fat contributes to the aortomesenteric angle, which is considered normal between 28-65 degrees.1,3 Other underlying causes of SMA syndrome include congenital variants like anomalies of the origin of the SMA, visceral ptosis, adherences secondary to malrotation, and accentuated lumbar lordosis.2

Plain abdominal radiographs can show a dilated and distended stomach. Upper GI studies usually demonstrate abrupt vertical or oblique cutoff of contrast at the level of the third segment of the duodenum. Real-time observation will demonstrate antiperistaltic waves proximal to obstruction. Repositioning the patient to the left posterior oblique position during the exam can advance the contrast to the distal duodenum. CT and MRI can demonstrate the relationship of the superior mesenteric artery to the aorta and the underlying duodenum. The caliber of the duodenum can also be assessed. Longitudinal ultrasound images with Doppler can also demonstrate the aortomesenteric angle.4

Treatment is usually conservative and includes nutritional support with proper positioning during feeding.3 Nasogastric feeding is often inadequate as food pools in the stomach and duodenum, proximal to the level of obstruction. Alternatively, total parenteral nutrition is often utilized; however, it is not ideal due to its relatively high expense, need for inpatient stay and potential complications.

Nasojejunal (NJ) feeding, which bypasses the narrowed distal duodenum by positioning a feeding tube tip distal to the region of small bowel compression, is the preferred approach in many institutions to provide nutritional support. An interventional radiologist places the NJ feeding tube under fluoroscopic guidance. The ultimate goal is weight gain and restoration of the retroperitoneal fat. This in turn increases the aortomesenteric angle and relieves the extrinsic compression of the superior mesenteric artery on the underlying duodenum. Normal peristalsis returns, food is propelled distally, and normal GI function is restored.

If conservative management fails, surgical management includes duodenojejunostomy, gastrojejunostomy, or even lysis of the ligament of Treitz with derotation of the bowel (Strong procedure) may be utilized.1,3

CONCLUSION

Superior mesenteric artery compression syndrome should be considered in a patient with rapid weight loss who presents with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. It is an important entity to recognize because it can be readily treated with nutritional support. Failure to recognize the disease can lead to a perpetual cycle of weight loss and vomiting leading to further clinical deterioration.

REFERENCES

- Lamba R, Tanner D, Sekhon S, McGahan J, Corwin M, and Lall C. Multidetector CT of vascular compression syndromes in the abdomen and pelvis. RadioGraphics. 2014;34:1,93-115.

- Neri S, Signorelli SS, Mondati E, et al. Ultrasound imaging in diagnosis of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. J Intern Med. 2005;257(4):346-351.

- Agrawal, GA, Johnson PT, Fishman EK. Multidetector row CT of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:62-65.

- Kothari TH, Machnicki S, Kurtz L. Superior mesentery artery syndrome. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011 25(11):599-600.

Citation

Superior Mesenteric Artery Compression Syndrome. Appl Radiol.

November 5, 2014