Bilateral adrenal neuroblastoma

Images

Neuroblastoma. Serum and urine catecholamine levels showed mild elevation of serum homovanillic acid (HVA) and urine vanillylmandelic acid (VMA). Histological study confirmed the diagnosis of neuroblastoma.

Findings

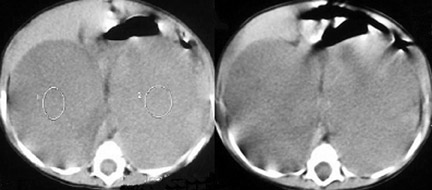

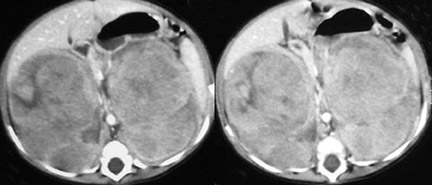

Sonography of the abdomen demonstrated a bilateral, mixed echogenic mass, enveloping the upper poles of the kidneys. These masses flattened and displaced the kidneys inferiorly (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) showed bilateral large masses in the paravertebral region, compressing the upper poles of the kidneys, and crossing the midline, displacing vessels (Figure 2). No calcifications were present in either mass and there was no retroperitoneal adenopathy or hepatic abnormality.

Discussion

Neuroblastoma is a poorly differentiated neoplasm derived from neural crest cells. It is one of the most common malignant tumors of childhood, with 40% arising in the adrenal glands. Bilateral adrenal involvement from synchronous development or metastatic spread of the tumour is seen in less than 10% of children with neuroblastoma. More than one third of cases (36%) are diagnosed in children younger than 1 year. The male-to-female sex ratio is 1.2 to 1. Some patients exhibit a hereditary predisposition for neuroblastoma, such as in cases with apparent familial, bilateral or multifocal disease. In these subsets of patients, the median age at diagnosis is 9 months.1-3

Neuroblastoma has been called "the great mimicker" because of its myriad clinical presentations related to the site of the primary tumour, metastatic disease and its metabolic tumor by-products. Most neuroblastomas produce catecholamines, which result in some of the most interesting presentations observed in children with neuroblastoma. For example, Kerner-Morrison syndrome causes intractable secretory diarrhea, resulting in hypovolemia, hypokalemia, and prostration.1-3

On ultrasonography, an adrenal neuroblastoma appears as a suprarenal heterogeneous echogenic mass. Ultrasonography can show urinary obstruction, vascular displacement and compression, nodal involvement, tumor extent, and liver involvement. However neuroblastomas are often large, and when they spread throughout the abdomen and/or into the chest, ultrasound may not be able to define their precise edges. It has limited ability to detect metastases in retroperitoneal and retrocrural lymph nodes and is usually unable to detect extradural extension oftumors.4-5

On CT, neuroblastoma appears as a lobulated, soft-tissue mass, either homogeneous or heterogeneous, which is caused by hemorrhage,necrosis, and/or calcification. Calcification has been reported on CT in approximately 85% of patients. CT can show prevertebral extension of tumor across the midline as well as encasement of the celiac axis or superior mesenteric artery by the neuroblastoma. It can also show extension of tumor to retroperitoneal lymph nodes, to the liver, around central vessels, and into the vertebral canal. CT is excellent for demonstrating retrocrural and paravertebral tumor extension to the chest, common in abdominal neuroblastoma.4-7

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is excellent for evaluating the location, extent and spread of neuroblastoma and the tumor shows equal or lower signal intensity on T1-weighted images and higher signal intensity on T2-weighted images compared with muscle. The center of the tumor is often heterogeneous, reflecting the presence of hemorrhage, necrosis or calcification. Advantages of MRI over CT and ultrasonography include: multiplanar imaging (useful for assessing invasion of adjacent organs); detection of extradural tumor extension; identification of bone marrow metastases (useful for staging); and, delineation of intra-abdominal vascular displacement or encasement without using intravenous contrast media.5-7

The treatment of neuroblastoma depends on the age of the child and the stage of the tumor. Surgery is indicated for stage 1 and 2 tumors while chemotherapy and radiation are the primary treatment modalities for advanced tumors.

CONCLUSION

The bilateral neuroblastoma is a rare entity. Medical imaging is very helpful in the diagnosis and the staging of this tumor.

- Kramer SA, Bradford WD, Anderson EE. Bilateral adrenal neuroblastoma. Cancer. 1980;45: 2208-2212.

- Cassady C, Winters WD. Bilateral cystic neuroblastoma: Imaging features and differential diagnoses. Pediatr Radiol. 1997;27:758-759.

- Kushner BH, Gilbert F, Helson L. Familial neuroblastoma: Case reports, literature review, and etiologic considerations. Cancer. 1986;57:1887-1893.

- Saks JB, Bryan PJ, Yulish BS, et al. Comparison of computed tomography and ultrasound in the evaluation of abdominal neuroblastoma. J Clin Ultrasound. 1985;13(9):641-645.

- Velaphi SC, Perlman JM. Neonatal adrenal hemorrhage: Clinical and abdominal sonographic findings. Clin Pediatr. 2001;40(10):545-548.

- Swischuk LE. Genitourinary tract and adrenal glands. In: Imaging of the Newborn, Infant, and Young Child. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1997:663-667.

- Siegel MJ. Pediatric applications. In: Lee JKT, Sagel SS, Stanley RJ, Heiken JP, eds. Computed Body Tomography with MRI Correlation. 3rd ed. Phila delphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven;1998:1523-1524.