5-year-old male with right flank pain

Images

Case summary

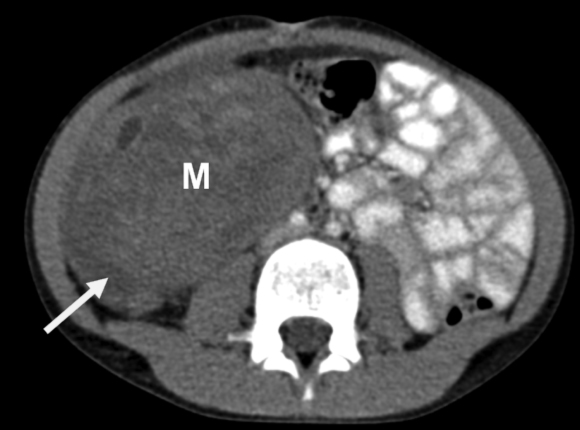

A 5-year-old, previously healthy boy presented to an outside hospital with right-flank pain and emesis after relatively minor blunt trauma to the abdomen. He had marked tenderness and a palpable mass in the right flank. Outside hospital imaging revealed a large right-renal mass with surrounding hematoma. After being transferred to Children’s Hospital, he underwent a biopsy followed by a staging computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis.

Imaging findings

The contrast-enhanced CT study was performed on a Somatom Definition AS 64-slice scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). To minimize dose, images were acquired only in the portal-venous phase 50 sec after the start of the contrast administration and the lowest milliamperge (mA) and kilovoltage (kV) settings based on CARE DOSE 4D (automated mA selection) and CARE kV (automated kV selection) were used. Other scanning parameters were 0.6-mm collimation, pitch of 1 and 0.33-sec gantry rotation. CT dose index (CTDI) volume was 3.58 mGy and dose length product (DLP) was 119 mGy-cm. Using the conversion factor (0.002 mSv-(mGy-cm)1 for abdomen and pelvis examinations at 5 years of age, effective dose (E) was estimated to be 2.38 mSv (119 × 0.02). Axial images were used for tumor detection and determination of regional and distant spread. Coronal and sagittal reformations were used to assess craniocaudal tumor extent.

A 10.3 × 9.3 × 8.8-cm heterogeneously enhancing, exophytic soft-tissue mass was seen arising from the lower pole of right kidney. A ‘claw sign’ (renal parenchyma cupping the mass) was demonstrated confirming the renal origin. There were small areas of necrosis, but no calcifications or fat densities. There was invasion of the perinephric fat. The upper pole of the right kidney and right adrenal gland were spared. Single right renal artery and vein were demonstrated, which were patent and normal in caliber. The inferior vena cava was markedly attenuated, but patent above and below the level of the mass. There was no retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy or liver metastasis. The patient subsequently underwent radical nephrectomy and started chemotherapy.1 for abdomen and pelvis examinations at 5 years of age, effective dose (E) was estimated to be 2.38 mSv (119 x 0.02). Axial images were used for tumor detection and determination of regional and distant spread. Coronal and sagittal reformations were used to assess craniocaudal tumor extent.

A 10.3 x 9.3 x 8.8-cm heterogeneously enhancing, exophytic soft-tissue mass was seen arising from the lower pole of right kidney. A ‘claw sign’ (renal parenchyma cupping the mass) was demonstrated confirming the renal origin. There were small areas of necrosis, but no calcifications or fat densities. There was invasion of the perinephric fat. The upper pole of the right kidney and right adrenal gland were spared. Single right renal artery and vein were demonstrated, which were patent and normal in caliber. The inferior vena cava was markedly attenuated, but patent above and below the level of the mass. There was no retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy or liver metastasis. The patient subsequently underwent radical nephrectomy and started chemotherapy.

Diagnosis

Wilms tumors

Discussion

Wilms tumor (nephroblastoma) is the most common renal malignancy in children.2 Affected children usually present before 5 years of age (mean age is 3 years). The common clinical finding is a palpable abdominal mass. Other findings include abdominal pain, fever, microscopic or gross hematuria, and hypertension.

Occasionally, patients present with Budd-Chiari syndrome secondary to hepatic vein invasion by tumor. Associated abnormalities, such as Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, (hemihypertrophy, omphalocele, macroglossia, and visceromegaly), nonfamilial aniridia, congenital hemihypertrophy, WAGR (Wilms tumor, aniridia, genitourinary malformation, mental retardation) and Denys-Drash (aniridia and ambiguous genitalia), are occasionally promptly evaluated. Approximately, 10% of children have metastatic disease at presentation. Metastases are characteristic to the lungs and less often to the liver.

On gross examination, Wilms tumor is a bulky mass that replaces most of the involved kidney. It arises within the cortex and grows in an exophytic fashion, with the bulk of the tumor protruding from the kidney. The tumor is surrounded by a rim of compressed renal tissue, termed a pseudocapsule, and often contains foci of necrosis or hemorrhage.

The staging of Wilms tumor is based on surgical and pathologic examinations. Treatment of Wilms tumor is radical nephrectomy and chemotherapy.1 The two-year relapse free survival for all stages of disease combined is approximately 90% and the overall survival is 96%.2

The goals of imaging in a patient with Wilms tumor are characterization of the tumor and determination of the extent of regional and distant tumor spread. CT is still the study of choice to confirm the renal origin of the tumor, its margins, and local and distant extension. Wilms tumor characteristically appears as a large, spherical, at least partially intrarenal low-attenuation mass. The tumor may be homogeneous, but more often it is heterogeneous containing focal areas representing necrosis, hemorrhage, or cystic degeneration.3,4

Local spread of tumor may take the form of extension through the capsule into the perinephric space, retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, or renal vein or inferior vena caval thrombosis. Perinephric extension appears as a thickened renal capsule or as infiltration of the perinephric fat. Lymph node involvement appears as enlarged perirenal, paracaval, paraaortic, retroperitoneal or retrocrural lymph nodes.

Tumor thrombus is seen as a low-attenuation intraluminal mass in the renal vein or inferior vena cava. Involvement of the renal vein or inferior vena cava does not adversely affect stage or prognosis if appropriate treatment is given. Tumor thrombus extending to or above the confluence of the hepatic veins may require a thoracoabdominal approach to prevent tumor embolization to the pulmonary arteries. Tumor below the hepatic veins can be removed by an abdominal approach. Bilateral tumors are usually synchronous (occurring simultaneously) rather than metachronous (occurring at different times). The CT findings are a dominant mass with a smaller contralateral tumor or a dominant mass in each kidney.

Conclusion

A soft-tissue intrarenal mass in a young child is most likely to represent Wilms tumor. Low-dose CT with coronal and sagittal reconstructions play a very important role in establishing the diagnosis and staging the tumor.

References

- International Commission on Radiological Protection. 1990 recommendations of the international commission on radiological protection (Report 60). Ann ICRP. 1991;21;1-3.

- Dome JS, Perlman EJ, Ritchey ML, et al. Renal tumors. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, eds. Pediatric Oncology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:905-932.

- Siegel MJ. The Kidney. In: Siegel MJ, ed. Pediatric Body CT. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:282-321.

- Lowe LH, Isuani BH, Heller RM, et al. Pediatric renal masses: Wilms tumor and beyond. RadioGraphics. 2000; 20:1585-1603.