17-year-old male not walking well

Images

Summary

A 17-year old Hispanic boy presented with a history of “not walking well” and an inability to run since age 4. He sought medical attention following a recent progression to walking only with the assistance of others. The patient described considerable numbness and weakness in his entire left leg without pain and denied these symptoms in his right leg or his back. He denied any relevant medical history, medications, allergies, or family history of similar symptoms or thyroid or pituitary conditions. The patient measured 5 feet 5 inches tall and weighed 150 pounds (body mass index = 25).

Imaging findings

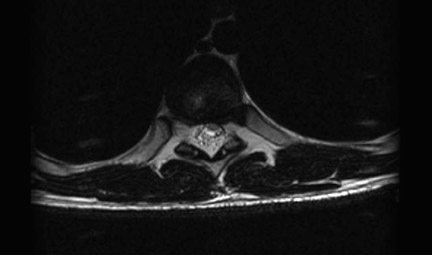

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the thoracic spine was performed in the axial and sagittal planes using T1-weighted (T1W), T2weighted (T2W), and short tau inversion recovery sequences. MRI revealed a prominence of the epidural fat along the posterior aspect of the thecal sac from T5 through T10, greatest at the T8–T9 level, with a sagittal epidural fat thickness of approximately 8 mm at this level. There was also associated ventral displacement of the spinal cord (Figure 1). Axial T1W and T2W images also showed the prominence of the epidural fat with ventral displacement of the spinal cord and narrowing of the spinal canal at the T8 level (Figure 2).

Diagnosis

Spinal epidural lipomatosis (SEL)

Discussion

Spinal epidural lipomatosis is characterized by pathological hypertrophy of adipose tissue located in the spinal epidural space producing thecal sac compression. It was first described by Lee et al1 in 1975 in a patient after renal transplantation. Since then, reports have drawn a distinct correlation between long-term administration of steroid and hypertrophy of adipose in the extradural space, associating this with the general increase in adipose tissue deposition associated with Cushing’s syndrome.2 Spinal epidural lipomatosis has been associated with Cushing’s disease, Cushing’s syndrome, hypothyroidism, pituitary prolactinoma, radiotherapy, obesity, and idiopathic causes.2,3 However, it is most commonly caused by long-term steroid use (most often via oral administration), which is found in approximately 75% of reported cases.4 Its occurrence is unpredictable and does not correspond to the dosage or duration or steroid use.5 It is considered rare, but there have been more reported cases than previously thought. The prevalence of SEL is unknown, but many well-documented cases exist.3 Spinal epidural lipomatosis is found more often in males (75%) than females with a mean age of 43 years, but has been reported in boys as young as 6 years of age who were on high-dose steroid treatment.2

Clinical manifestations most commonly include back pain followed by lower extremity weakness, which is usually slowly progressive but may also include numbness and bladder or bowel dysfunction. Symptoms depend on region of canal compromise. The thoracic region is most commonly involved, which produces myelopathic effects, while lesions in the lumbar region tend to cause radiculopathic effects. On physical examination, lower extremity weakness is the most common finding, although decreased pinprick sensation and altered reflexes have also been found.6-8 Direct compression of the spinal cord and its resulting symptoms require further investigation into differential diagnoses, aside from the imaging modalities that can point to SEL.

The imaging modality of choice for SEL is spinal MRI. On conventional spin-echo MRI, fat shows increased signal intensity on noncontrast T1W images and intermediate signal intensity on T2W images. The MRI findings have typically shown sagittal epidural fat thickness between 7 and 15 mm (normal is 3 to 6 mm) with subsequent thecal sac compression. Spinal epidural lipomatosis is most commonly found at the T6–T8 levels of the thoracic spine and at the L4–L5 levels of the lumbosacral region, with approximately 60% of cases involving the thoracic cord and 40% with lumbar involvement.4,6,7 However, idiopathic SEL has no predominance of either thoracic or lumbar regions.6,9,10 MRI of SEL typically shows the adipose tissue located posterior and posterolateral to the dural sac, compressing the cord anteriorly.11,12 The high contrast between adipose tissue and the thecal sac on T1W MRI permits an accurate evaluation of the extent of pathologic epidural adipose tissue overgrowth in the spinal canal, thus making MRI ideal for diagnosis of this condition.13 According to a study by Quint et al,11 epidural lipomatosis should be considered when:

- A complete posterior block is seen at myelography;

- Computed tomography (CT) or MRI reveals only fat contiguous to a ventrally displaced dural sac;

- There is a history of chronic steroid use;

- There are myelopathic or radicular symptoms referable to the level of the abnormality; or

- There are no other structural lesions that could help explain the symptoms and imaging findings.

CT scanning shows a soft tissue extradural mass with low attenuation. Gross and histological examinations show a normal, diffuse unencapsulated deposit of adipose tissue in SEL, which distinguishes it from a well-defined, focal encapsulated extradural lesion, such as lipoma, infection, cyst, or neoplasm.10,12

The treatment for steroid-induced SEL includes the reduction of glucocorticoid excess and an increase in physical activity. The treatment for SEL associated with obesity is weight loss, but it has been reported that a weight reduction of ≥15 kg is necessary.6

For cases unresolved by the above treatments or cases with severe cord compression and neurological deficits, decompressive laminectomy with excision of epidural fat is recommended. In addition, in patients with compression fracture secondary to steroid-induced osteoporosis, fusion surgery may be necessary to improve spinal stability.5 For patients with SEL who do not respond to conservative methods of treatment, this remains the optimal mode of management for relief of symptoms. Such surgery has an approximately 80% success rate6; however, it also has a 22% postoperative mortality, which is most likely due to the immunocompromised status induced by steroid7,10 Postoperatively, repeat images and close follow-up are necessary.

Conclusion

For a patient who presents with persistent back pain or leg weakness, pain, or paresthesias, SEL should be included in the list of differential diagnoses and investigated via MR imaging. Specific attention should be directed to the appearance of the epidural fat in order to make a prompt diagnosis, so that appropriate treatment may be initiated and complications of cord compression can be avoided.

References

- Lee M, Lekias J, Gubbay SS, Hurst PE. Spinal cord compression by extradural fat after renal transplantation. Med J Aust. 1975;1:201-203.

- Fassett DR, Schmidt MH. Spinal epidural lipomatosis: A review of its causes and recommendations for treatment. Neurosurg Focus. 2004; 16(4):E11.

- Fan CY, Wang ST, Liu CL, et al. Idiopathic spinal epidural lipomatosis. J Chin Med Assoc. 2004;67:258-261.

- Stern JD, Quint DJ, Sweasey TA, Hoff JT. Spinal epidural lipomatosis: Two new idiopathic cases and a review of literature. J Spinal Disord. 1994;7:343-349.

- Chen CC, Lee WY, Cho DY. Spinal epidural lipomatosis. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei).2002;65:86-89.

- Robertson SC, Traynelis VC, Follett KA, Menezes AH. Idiopathic spinal epidural lipomatosis. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:68-74; discussion 74-75.

- Fessler RG, Johnson DL, Brown FD, et al. Epidural lipomatosis in steroid-treated patients. Spine. 1992;17:183-188; comment in: Spine. 1992;17:1268.

- Roy-Camille R, Mazel C, Husson JL, Saillant G. Symptomatic spinal epidural lipomatosis induced by a long-term steroid treatment. Review of the literature and report of two additional cases. Spine. 1991;16:1365-1371.

- Randall BC, Muraki AS, Osborn RE, Brown F. Epidural lipomatosis with lumbar radiculopathy: CT appearance. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1986; 10:1039-1041.

- Kumar K, Nath RK, Nair CP, Tchang SP. Symptomatic epidural lipomatosis secondary to obesity. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:348-350.

- Quint DJ, Boulos RS, Sanders WP, et al. Epidural lipomatosis. Radiology. 1988;169:485-490.

- Greiner FG, Takhtani D. Neuroradiology case of the day. Extradural lipomatosis. RadioGrapics. 1999;19:1397-1400.

- Lee RKT, Chau LF, Yu KS, Lai CW. Idiopathic spinal epidural lipomatosis. A case report. J HK Coll Radiol. 2002;5:105-108.