What radiologists need to know about injectable facial fillers

As populations age in affluent economies, the number of women — and even men — having cosmetic injectable facial rejuvenation treatments is skyrocketing. Radiologists need to be knowledgeable of the appearances of fillers to avoid misinterpretation of magnetic resonance (MR) and positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET-CT) examinations. An article in Insights into Imaging provides a detailed, concise, and well-illustrated review.

In 2016, injections of hyaluronic acid (HA) alone in the United States totaled nearly 2.5 million procedures, according to the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ASAPS). ASAPS statistics reveal that use of injectable fillers in the body increased 21% between 2014 and 2015. The most commonly injected sites on the face include the perioral area, pericular region, nasolabial folds, malar fat pad, marionette lines, glabella and lips.

Radiologists at Geneva University Hospital and Sion Hospital in Switzerland advise that it is very important for radiologists to be able to know protocols most appropriate for imaging patients with facial fillers and also to be alert to their appearance in patients who do not report this in their clinical history. Minerva Becker, MD, head of the department for head and neck and maxillo-facial radiology in the Division of Radiology at the Hôpitaux Universitaires de Genève, and co-authors caution that incidentally detected facial fillers can be diagnostically challenging, especially of a patient denies the procedure or does not know the type of filler injected. Their article includes a review of the anatomy of facial fat compartments and a detailed description of the properties and imaging features of commonly used autologous, biological, and synthetic facial fillers. The authors also describe complications, some pitfalls in interpretation, and dermatologic conditions mimicking filler-related complications.

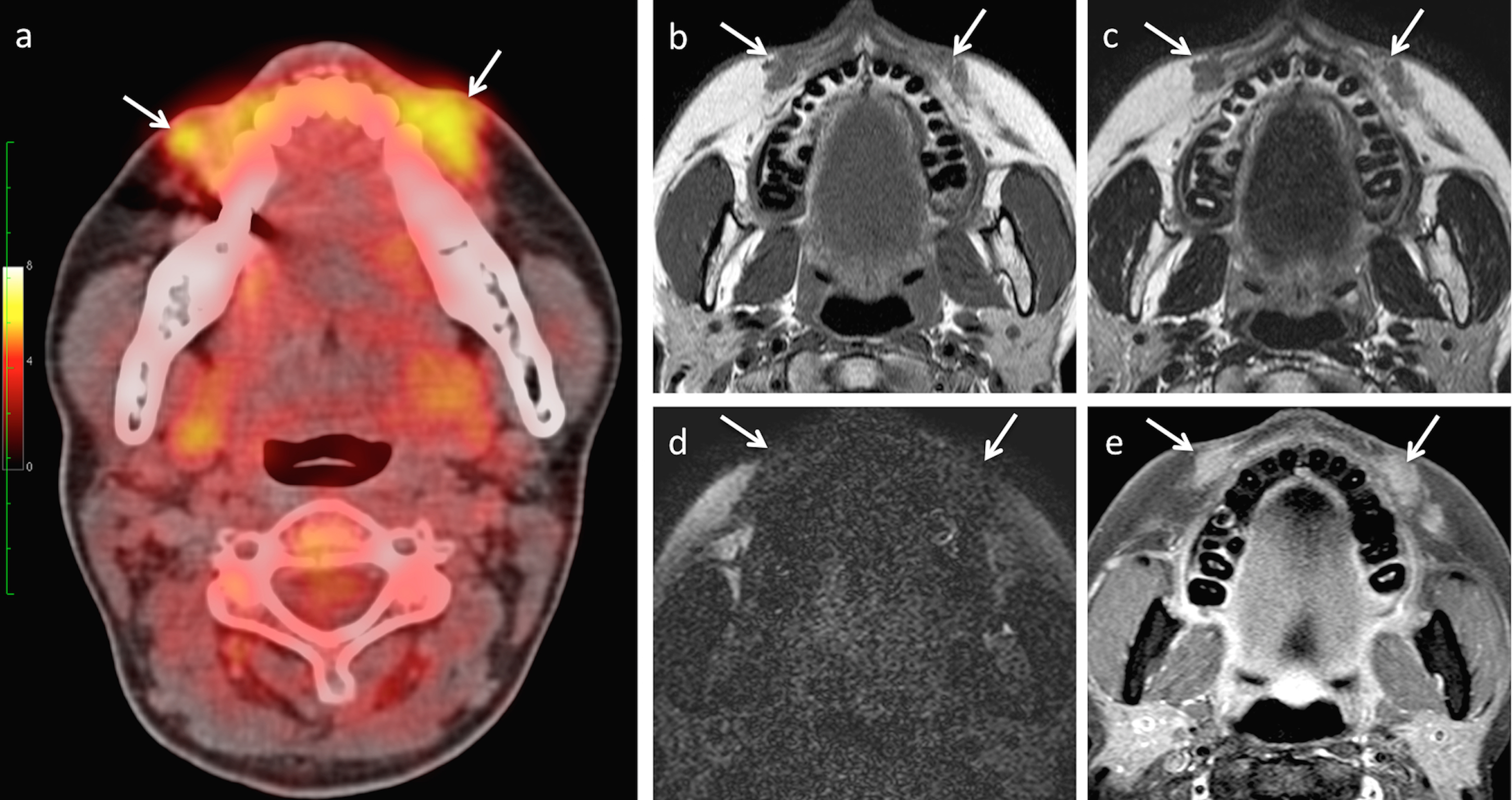

Biopsy-proven foreign body granulomas caused by injection with Poly-l-lactic acid. FDG PET CT (a) performed for lymphoma staging shows two perioral nodular lesions (arrows) with avid FDG uptake (SUVmax = 8; SUVmean = 6). On MRI, the diffusely infiltrating nodules appear hypointense on T1W (b), T2W (c) and on the silicon-only sequence (d), and they show contrast-enhancement on the fat saturated post-gadolinium T1W sequence (e). There was no restricted diffusion on diffusion-weighted imaging (not shown). Imaging findings strongly suggested the diagnosis of foreign body granulomas as a complication of facial filler injection; the diagnosis was confirmed by biopsy

Identifying filler-related complications on imaging

All types of injectable facial fillers can cause short-term and long-term complications. Diagnostic imaging is valuable for identifying the formation of abscesses, noninflammatory nodule and foreign body granulomas, overfilling and migration of fillers, scarring, and lymph node enlargement.

Permanent fillers — typically silicone — tend to migrate through lymphatic or hematogenous routes. They may mimic a malignant pathology of distant organs. Overfilling may appear as a lump or diffuse facial asymmetry. Severe chronic inflammatory thickening can be identified as a thick band-like subcutaneous deposition of silicone associated with diffuse. soft-tissue swelling and post-contrast enhancement.

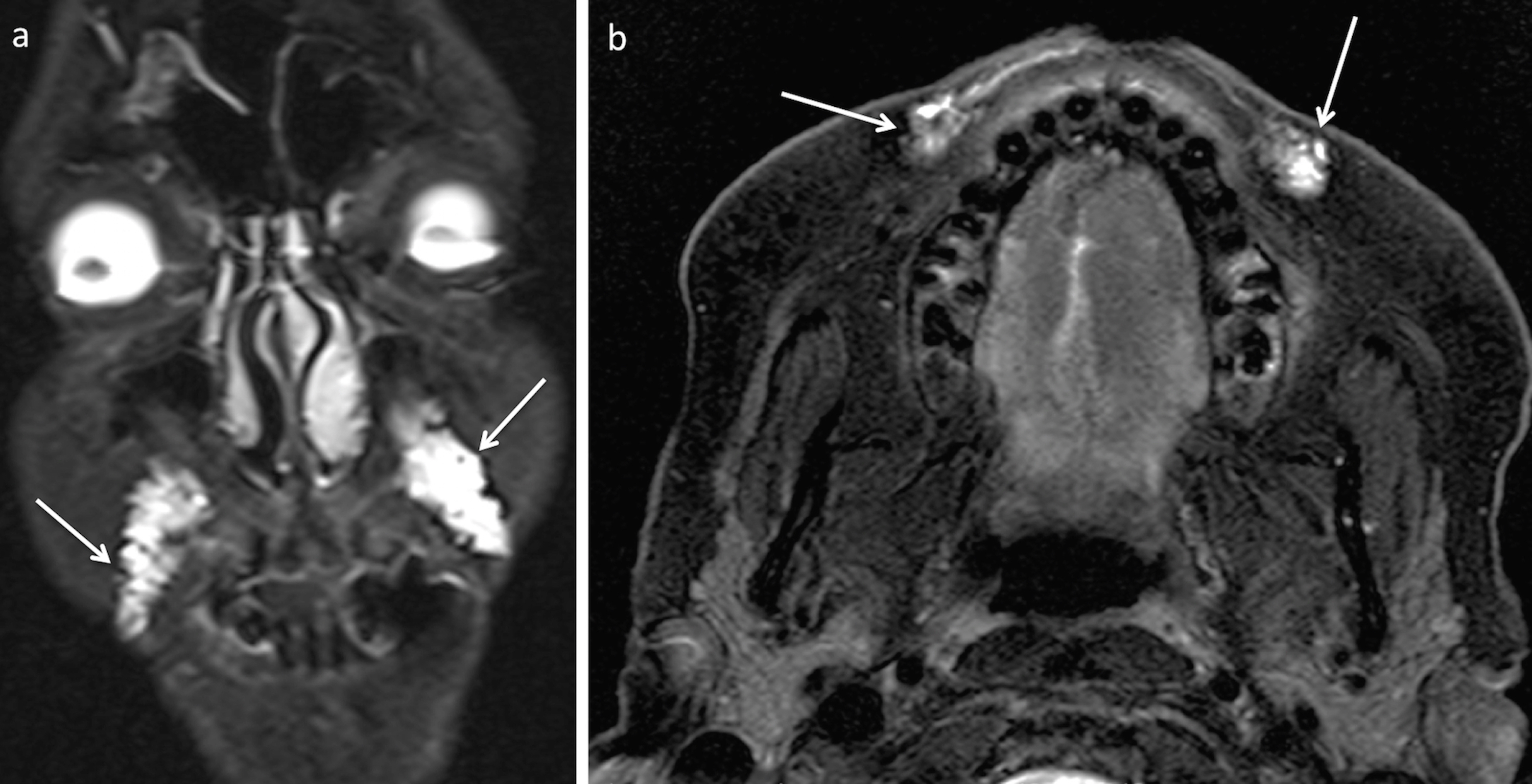

Characteristic aspect of facial filler injection for rejuvenation purposes. High signal intensity areas along the nasolabial folds and perioral areas incidentally detected on fat saturated coronal (a) and axial (b) T2W images. The patient confirmed previous injection of hyaluronic acid.

Filler-related abscess is visualized as a lobulated fluid collection with rim enhancement and adjacent fat stranding on MRI. Restricted diffusion may be visible when diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) is performed,

The authors write that development of non-inflammatory nodules (NIN) and foreign body granulomas (FBGs) differ both on imaging and histopathology and that distinguishing these complications is important because their clinical management of each differs. They explain that NINs are single lumps, which usually appear within 4-8 weeks after filler injection but can subsequently be seen for years. On imaging, they are evenly sized, appear harder and whiter than granulomas, and remain stable over time. FBGs appear on imaging months to years after filler injection. They grow slowly, can be multiple, and can recur after treatment. The authors explain that their appearance on imaging varies considerably, but based on their own experience, FBGs show enhancement on MRI. Computed tomography (CT) scans may show punctuate or eggshell classifications.

Imaging techniques

The authors recommend MRI to assess the location and volume of the injected facial fillers and to evaluate filler-related complications. They prefer MRI over ultrasound because of its excellent soft tissue discrimination capability, large field of view, and ability to provide anatomic, quantitative, and functional information. MRI provides anatomical reference for the localization of dislodged fillers, a capability that ultrasound imaging does not have. However, high frequency ultrasound can detect superficially located filler-related complications. PET-CT is not recommended because the increased18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake associated with injectable fillers may mimic a malignant tumor or an infectious process.

The recommended MRI examination protocol includes high-resolution, thin-slice acquisitions on a 1.5 or 3 Tesla scanner with surface coils and parallel imaging techniques. They acquire axial T1W, T2W ± fat saturation or an axial and coronal STIR sequence, diffusion weighted sequences with axial ADC maps, and post-gadolinium injection T1W with fat saturation. A “silicone only” axial sequence with simultaneous water and fat saturation should also be performed before gadolinium injection if the type of the injected filler is unknown.

REFERENCE

- Mundada P, Kohler R, Boudabbous S, et al. Injectable facial fillers: imaging features, complications, and diagnostic pitfalls at MRI and PET CT. Insights Imaging 2017 8;6:557-572.