Klippel-Feil Syndrome Essentials, Part 2: Advanced Imaging Techniques and Diagnostic Strategies

Introduction

In part 1 of our review, we explored the embryological development and genetic foundations of Klippel-Feil syndrome (KFS), providing a critical understanding of its origins. Part 2 focuses on the more clinical aspects of KFS, including its diagnosis, associated conditions, and imaging techniques. We aim to address the challenges posed by the syndrome’s phenotypic variability and highlight the importance of imaging in confirming diagnoses and guiding treatment.

Imaging

Imaging is vital to confirm a suspected case of KFS as the patterns of fusion may aid in future follow-up and potentially screen for those at highest risk for developing spinal cord injury. Though less sophisticated than current KFS classification systems, one could broadly diagnose KFS in anyone with any degree of congenital cervical vertebrae fusion.1 - 3 Congenital fusions are demonstrated by osseous bridging between 2 or more vertebrae.4, 5 This fusion typically goes undetected until later in life when mechanical or neurological signs and symptoms may begin.6, 7 Diagnosis may be complicated owing to the natural ossification progression of the pediatric cervical spine. Ongoing ossification may make cervical synostosis difficult to appreciate on radiographic imaging.6 Pseudosubluxation, which can be normal in children less than 8 years old, particularly involving C2-C4, should not be mistaken for instability.8, 9

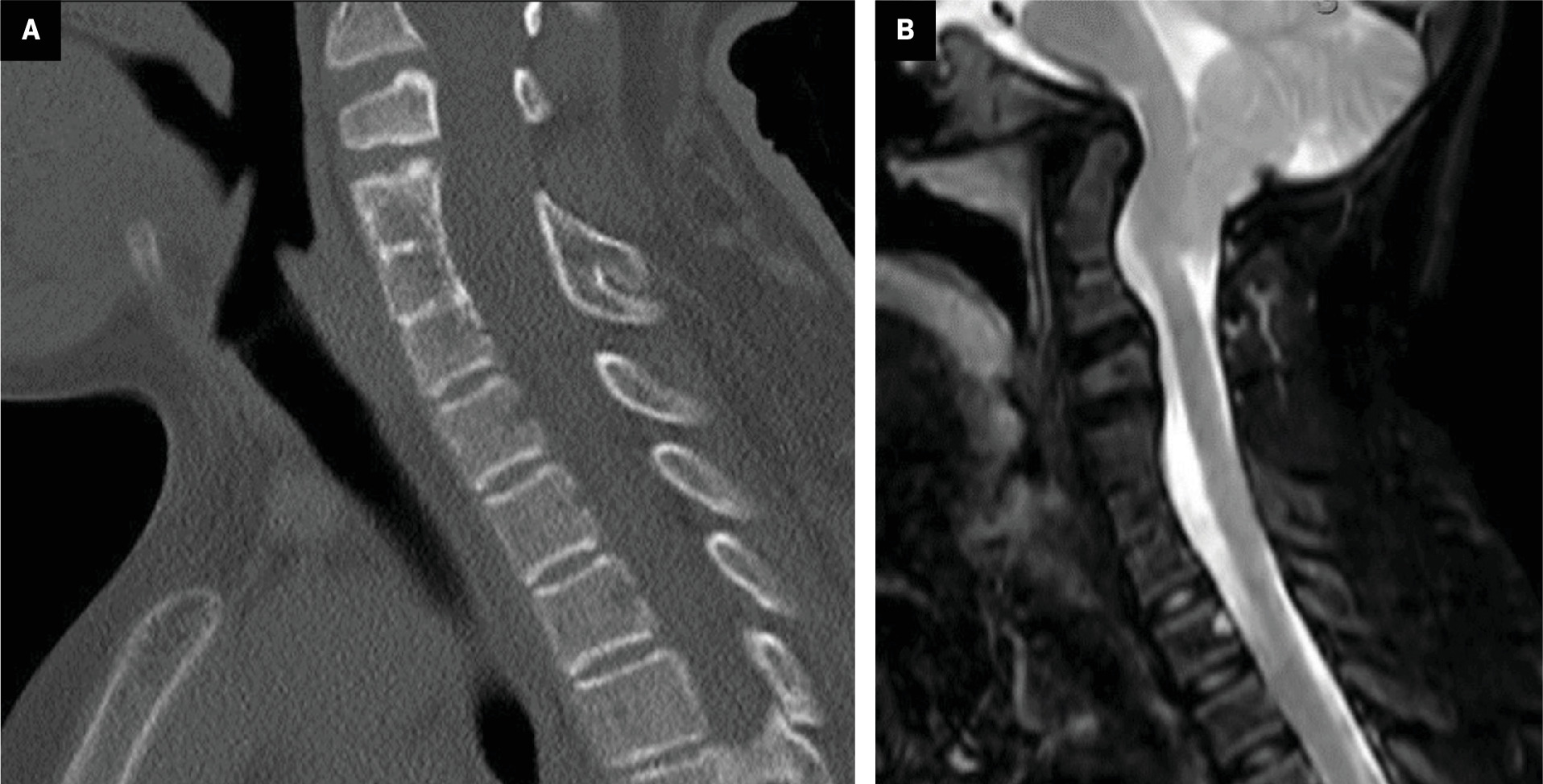

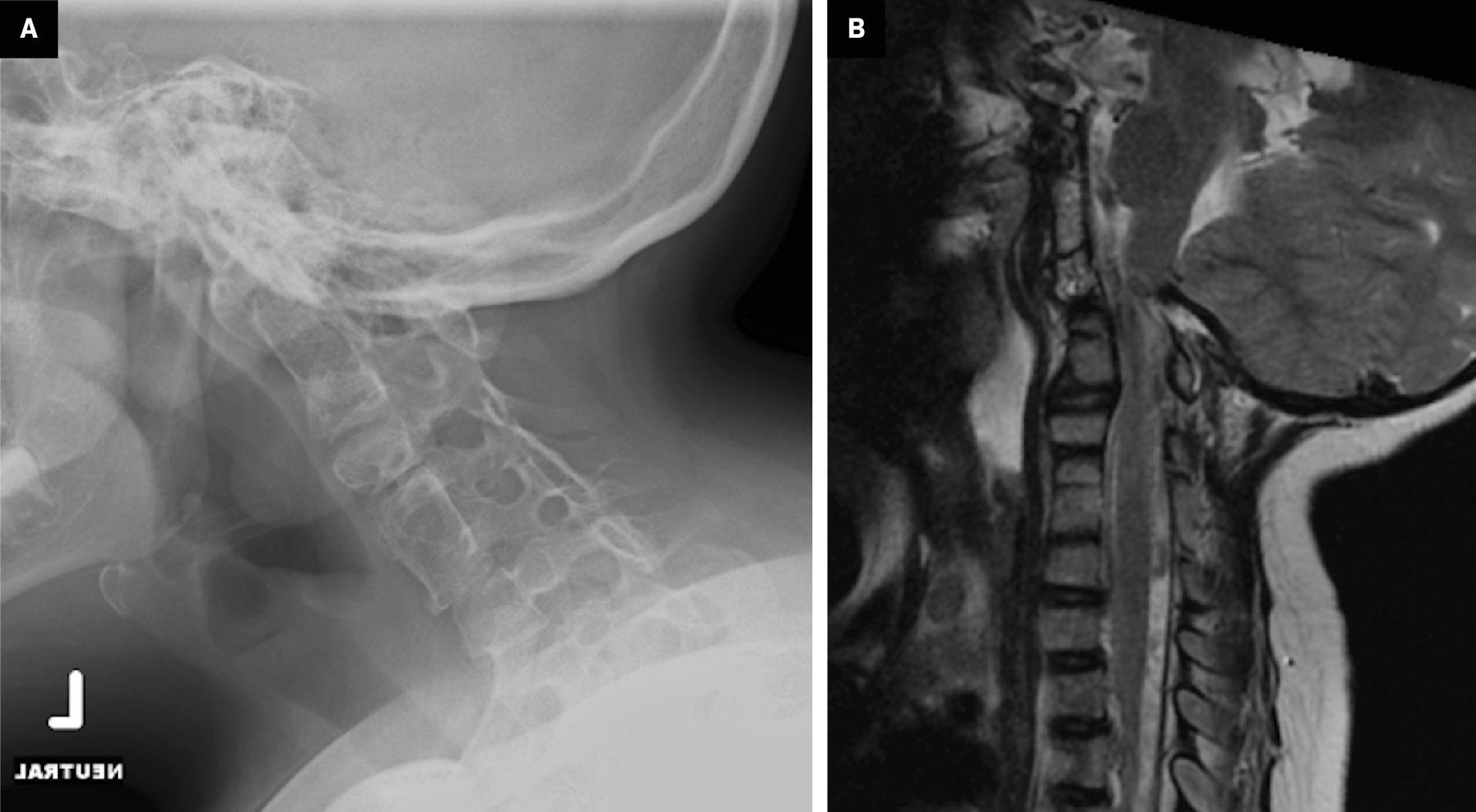

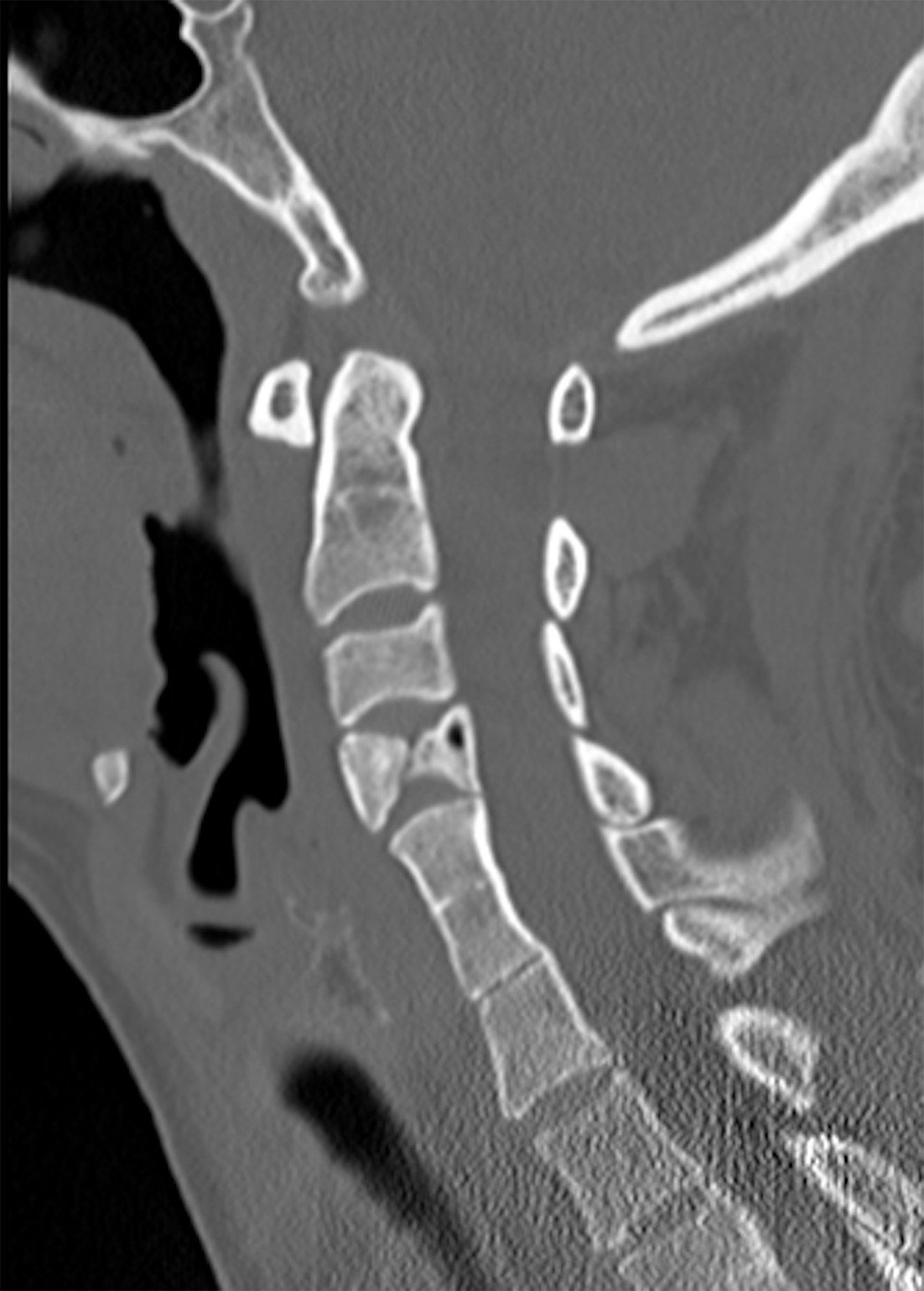

The original and most commonly used classification of KFS is based on the extent of the fusion. Type I involves massive fusion of cervical and upper thoracic vertebrae ( Figure 1 ). Type II is characterized by fusion at only 1 or 2 interspaces, often accompanied by other cervical spine anomalies such as hemivertebrae or atlantooccipital fusion ( Figure 2 ). Type III includes cervical fusions associated with lower thoracic or lumbar fusion ( Figure 3 ). Other classification systems were discussed in Part 1.

Type I Klippel-Feil syndrome (KFS). ( A ) Sagittal CT in bone window and ( B ) fat-saturated sagittal T2-weighted MRI show type I KFS with anterior and posterior fusion of C4-C6 and wedge-shaped C3. MRI also demonstrates the platybasia, cerebellar tonsillar ectopia, and basilar invagination with mass effect on the brainstem and the cervicomedullary junction.

Type II Klippel-Feil syndrome (KFS). ( A ) Lateral radiograph in neutral position and ( B ) sagittal T2-weighted MRI show type II KFS with multilevel anterior and posterior cervical vertebral fusion and atlantooccipital fusion. MRI also demonstrates significant upper cervical spinal canal narrowing.

Type III Klippel-Feil syndrome (KFS). Complete spine T2-weighted sagittal MRI showing type III KFS with fusion at C3-C4, C5-C6, T1-T2, L2-L3, and L4-L5 vertebra. Disc degeneration is observed in the superior C4-C5 junctional level.

A 2006 study by Samartzis et al5 examined the congenital fusion patterns of 28 predominantly pediatric patients with KFS. They classified type I as a single, congenitally fused cervical segment (25% of patients), type II as multiple, noncontinuous fused segments (50% of patients), and type III as multiple contiguous fused segments (25% of patients), with axial neck symptoms common in type I and radiculopathy and myelopathy more common with types II and III. Employing this same classification system, Gruber et al10 found that all 17 patients with KFS in their large retrospective CT review were Samartzis type I. They noted that vertebral levels C2-C3 and C5-C6 were the most commonly fused but that congenital scoliosis, a reportedly common finding in KFS,11, 12 was absent in their patients. Further research is needed to determine the prevalence of individual fusion patterns, but a region-specific classification system can provide insight into the risk of future symptom development.

Another classification described in 2008 by Samartzis et al4 categorizes fusion patterns in KFS as anterior, posterior, and complete fusion based on lateral radiographs. Anterior fusion involves interbody bridging, posterior fusion involves the facet joints, posterior arches, and spinous processes, and complete fusion includes both anterior and posterior fusion. Complete fusion may be seen radiographically as the “wasp-waist sign” ( Figure 4 ),13 an anterior indentation occurring at the interbody space of the fused segments.14

Segmentation anomaly in type I Klippel-Feil syndrome (KFS). Sagittal CT in bone window showing hemivertebrae at C4, a vertebral body segmentation anomaly commonly seen in KFS, with a “wasp-waist” sign at the level of fusion.

With this classification system in place, Samartzis et al4 then retrospectively looked at patients with KFS stratified by age and found that the prevalence of complete fusion increased with age, while incomplete fusion was more prevalent in younger age groups. The incompletely fused segments were most commonly posterior. Familiarity with the categories of fusion and their more commonly associated ages can aid in distinguishing KFS from changes related to juvenile rheumatoid arthritis,15, 16 fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva,17 - 19 ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament,20 and ankylosing spondylitis.

Atlantoaxial instability is a common risk factor in patients with KFS that could potentially lead to cervical spinal cord injury ( Figure 2 ). It is important to diagnose this instability because patients with hypermobility in the upper cervical region have been shown to be at the greatest risk for spinal cord injury.21 However, some suggest that hypermobility of the atlantoaxial junction does not definitely increase the risk for neurological signs.22

Spinal stenosis, another risk factor for cervical spinal cord injury in KFS,23, 24 is measured as the space available for the cord (SAC) and examined on lateral neutral radiographs.25 A SAC of <13 mm suggests an inadequate amount of space for the spinal cord; however, SAC typically increases at levels of congenital fusion.25 This suggests cervical injuries are more likely the result of hypermobility between fused and nonfused segments rather than stenosis.

The vertebral body width (VBW) may be a more reliable anatomical marker for assessing the risk of spinal cord injury. The VBW is measured at the midpoint of each body, including the fused segments, on anteroposterior radiographs. Patients with KFS show an average decrease in VBW of the fused segments compared with the nonfused segments, and this lower VBW has been associated with an increased prevalence of cervical spinal cord injury.25 This further supports the hypothesis that cervical spinal cord injuries are due to hypermobility because of the unequal articulating surface areas leading to facet joint instability. The difference of articulating surface areas may also explain the high prevalence of degenerative vertebral changes in KFS9, 26 ( Figure 5 ).

Degenerative changes in type I Klippel-Feil syndrome (KFS). Lateral radiograph in neutral position demonstrating type I KFS with fusion of C4-C7 and superior junctional degeneration changes in the C3-C4 vertebral bodies.

The cervical spinal cord has a smaller cross-sectional area in patients with KFS from the C2-C7 segments.27 This suggests a loss of axons, but it is not known whether the loss is secondary to mechanical stress on the spinal cord or developmental.27

Although cervical fusion is the hallmark of KFS, other spinal and appendicular skeletal abnormalities, including hemivertebrae, butterfly vertebrae, scoliosis, kyphosis, thoracic and/or lumbar fusion, cervical ribs, and bifid ribs, may be present ( Figure 4 ),28 - 31 highlighting the importance of imaging a KFS patient’s entire spine. Moreover, because of the array of visceral and sensory deformities associated with KFS, additional imaging is needed. At a minimum, patients should undergo imaging of their entire spine, renal ultrasound, neurological assessment, and auditory testing. Follow-up often includes annual cervical flexion and extension radiographs for higher-risk patients based on their fusion pattern. Lower-risk patients may undergo less frequent follow-up.32

Spine MRI is the preferred modality for assessing neuropathic symptoms such as myelopathy and radiculopathy as it can readily diagnose spinal cord abnormalities such as syringomyelia.33

Diagnosis and Clinical Associations

Clinicians forming treatment plans for patients with KFS must consider the association between KFS and other anomalies. Considerable phenotypic heterogeneity among patients with KFS has led to several cohort studies describing various presentations of the syndrome.22, 34, 35 These variations in phenotype may contribute to diagnostic challenges.36 Traditionally, patients with KFS have been identified by a triad of symptoms—a low-set hairline on the posterior head, a short neck, and limited neck movement—but fewer than 50% patients with KFS exhibit these characteristics.37, 38 Fusion patterns, the extent of fusion, and the location of the rostral-most fusion could serve as more accurate diagnostic criteria for KFS.

Klippel-Feil syndrome is often diagnosed after a patient presents to the clinician with related neurological symptoms, commonly nuchal rigidity and sensory motor disorders in the distal upper extremities.39, 40 Approximately 78% of patients with KFS have scoliosis.36 Neurological symptoms are present in about 25% of patients with KFS, which Rovreau et al41 have attributed to cervical hypermobility. A host of other craniofacial abnormalities have been associated with KFS, such as cleft palate, micrognathia, and dental anomalies.36 The literature reports additional, associated neurological pathologies, including Chiari type III malformation,42 Brown-Sequard syndrome,43 neurenteric cyst,44 meningocele,45 tetraplegia,46 split cord malformation,47 and multiple aneurysms.48

Non-neurological conditions, including genitourinary abnormalities ( Figure 6 ) and Sprengel deformity of the scapula ( Figure 7 ), are commonly found in patients with KFS,35, 49 with associated incidences of 65% and 35%, respectively.50 Chandra et al51 attribute the association between renal abnormalities and KFS to the simultaneous differentiation of the cervical vertebrae and genitourinary tract and proximity during embryonic development. A thorough examination for Sprengel deformity is warranted in patients with KFS regardless of the severity of their symptoms. KFS has also been associated with osteoarthritis of the temporomandibular joints,52 tricuspid valve regurgitation,53 complete lung agenesis,54 and congenital megacolon.55

Genitourinary abnormalities in Klippel-Feil syndrome. Axial T2-weighted MRI image showing an absent left kidney.

Sprengel deformity in Klippel-Feil syndrome (KFS). 3D reconstructed CT image demonstrates Sprengel deformity with scapular elevation in a patient with KFS.

Treatment

Klippel-Feil syndrome presents two challenges for planning treatment. The first is the need to correct the congenital fusion and prevent secondary complications. Fusion of the cervical vertebrae increases susceptibility to cervical disc degeneration, spondylosis, and eventual spinal canal stenosis.37, 56 A combined approach of skull traction, cervical bracing, and advising the patient to refrain from activities with the potential to cause cervical injury can be employed to defer surgery, alleviate symptoms, and minimize the potential of neurological complications from traumatic injury.57

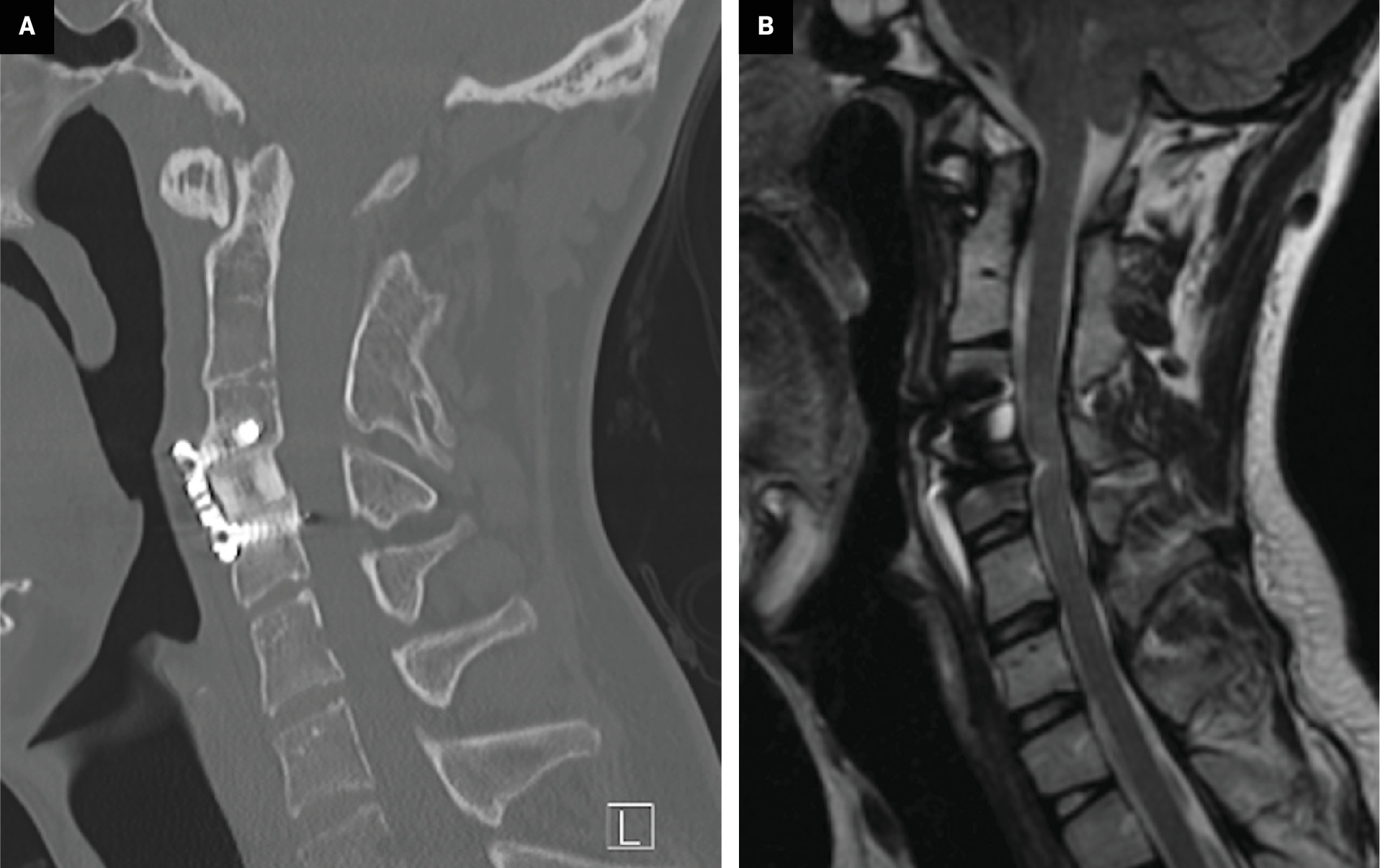

The second challenge is that KFS introduces additional complications that must be accounted for when treating other primary congenital abnormalities. In patients with basilar impression and KFS, surgical treatments usually involve an anterior approach, with the goal of spinal decompression. These can often be accompanied by surgical fusion to stabilize the spine ( Figure 8 ).

Postsurgical changes in Klippel-Feil syndrome (KFS). ( A ) Sagittal CT in bone window and ( B ) sagittal T2-weighted MRI (B) showing changes following anterior cervical discectomy, graft placement, and instrumented fusion of C4-C6 in a patient with KFS with congenital fusion of C2-C3.

Conclusion

Physicians and researchers can more accurately diagnose KFS and associated anomalies by conducting a thorough examination of embryology and molecular genetics. Understanding the classification systems allows for more accurate risk stratification and planning for initial and follow-up imaging.

References

Related Articles

Citation

Ritchey Z, Gunderson JR, Shaw Z, Kaddurah O, Greenhill M, King K, Mushtaq R.Klippel-Feil Syndrome Essentials, Part 2: Advanced Imaging Techniques and Diagnostic Strategies. Appl Radiol. 2025; (1):15-22.

doi:10.37549/AR-D-24-0056

February 7, 2025