HIV-related benign lymphoepithelial lesions

Images

HIV-related benign lymphoepithelial lesions (BLEL)

Findings

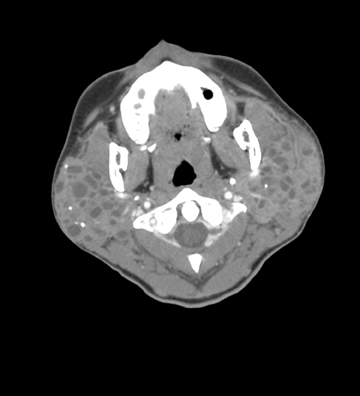

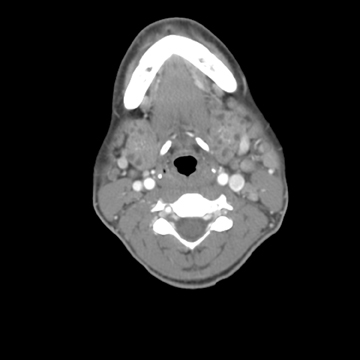

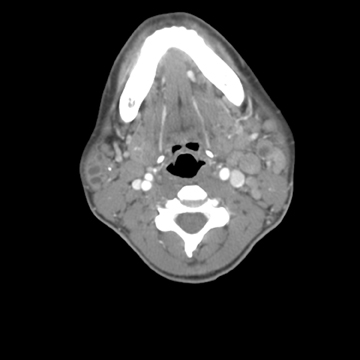

Contrast computed tomography (CT) imaging of the neck revealed bilateral enlarged parotid and submandibular glands with multiple intraparenchymal cysts (Figures 1 and 2). Punctate calcifications were scattered within the parotid glands, but no intraductal stones were present. Pertinent associated findings included bilateral enlarged level 1 and 2 cervical lymph nodes (Figure 3).

Discussion

Benign lymphoepithelial lesions of the parotid gland are a well-known entity associated with the AIDS- related complex; however, they are rare with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).1 Parotid gland swelling can be the initial presenting symptom of HIV infection.2 There can be a variety of radiological appearances on both CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Both complex cystic masses with solid components and homogenously cystic lesions can be seen.3 Lesions can be bilateral in up to half of patients.1

The pathophysiology of this disease process is debated. HIV-infected cells migrate into the parotid glands, which triggers lymphoid proliferation, inducing metaplastic changes in the salivary ducts.1 Cysts form due to ductal obstruction secondary to cellular proliferation.2 Since they arise from intralobar ducts, the cysts are not encapsulated.4 These cysts serve as a reservoir of HIV-1 p24 and RNA copies that are sometimes 1000-fold higher than plasma concentrations.1 A dramatic reduction in HIV-associated BLEL occurs with initiation of HAART.1

Many salivary gland diseases can contain either solid or cystic components. When gross pathology reveals cystic lesions, the incidence of malignancy is close to 1%; whereas for a solid mass, the incidence is closer to 40%.5 Differential diagnosis for unilateral lesions containing cysts includes sialolithiasis, first branchial cleft cyst, HIV-associated BLEL, adenoid cystic carcinoma, and benign mixed tumor.6 With bilateral disease, considerations include sialosis, sarcoid, systemic lupus erythematosis, and BLEL associated with either HIV or Sjogren’s syndrome.6 Warthin’s tumor and lymphoma can be either unilateral or bilateral; however, lymphoma is usually solid pretreatment.

Of these, Sjogren’s syndrome involves lymphoid infiltrates in the parotid glands and can cause both solid and cystic parotid lesions, also termed benign lymphoepithelial lesions. End-stage disease is characterized by a honeycomb glandular appearance. Rarely, diffuse bilateral macrocystic change can develop. Lymphoepithelial cysts associated with HIV infection are distinguished from Sjogren’s syndrome by the associated diffuse cervical lymphadenopathy.1,6

Conclusion

CT and MRI provide useful means for evaluating both unilateral and bilateral salivary gland enlargement. When patients present with enlarged parotid glands associated with cervical lymphadenopathy, HIV is the diagnosis of exclusion.

- Uccini S, D’Offizi G, Angelici A, et al. Cystic Lymphoepithelia lesions of the parotid gland In HIV-1 infection. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2000;14:143-147.

- Perling NM, Lin P, Lucente FE. Cystic parotid masses in HIV infection. Head Neck. 1990;12:337-341.

- Kirshenbaum KJ, Nadimpalli SR, Friedman M, et al. Benign lymphoepithelial parotid tumors in AIDS patients: CT and MR findings in nine cases. AJNR. 1991;12:271-274.

- Zeitlen S, Shaha A. Parotid manifestations of HIV infection. J Surg Oncol. 1991;47:230-232.

- Huang RD, Pearlman S, Friedman WH, Loree T. Benign cystic vs. solid lesions of the parotid gland in HIV patients. Head Neck. 1991;13:522-527.

- Brandwein MS, Som PM. Salivary Glands: Anatomy and Pathology. In: Som RM, Curtin HD, eds. Head and Neck Imaging, 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2003:2039-2050.

Citation

HIV-related benign lymphoepithelial lesions. Appl Radiol.

May 30, 2012