Giant solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura

Images

CASE SUMMARY

A 54-year-old man presented to the ER with chronic shortness of breath and wheezing. He had no significant medical or surgical history. The patient denied a history of tobacco use and asbestos exposure, and had no family history of lung cancer or pulmonary disease. On physical examination, he was afebrile with a normal cardiac exam. He had decreased breath sounds throughout the entire right hemithorax. All laboratory values were within normal limits.

IMAGING FINDINGS

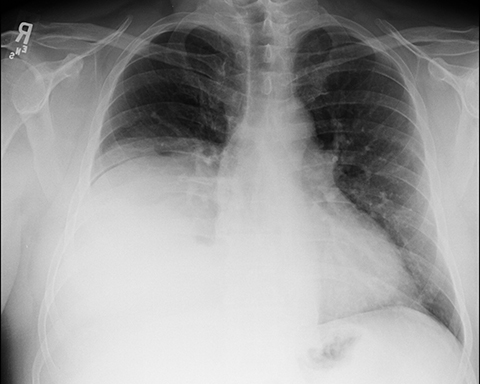

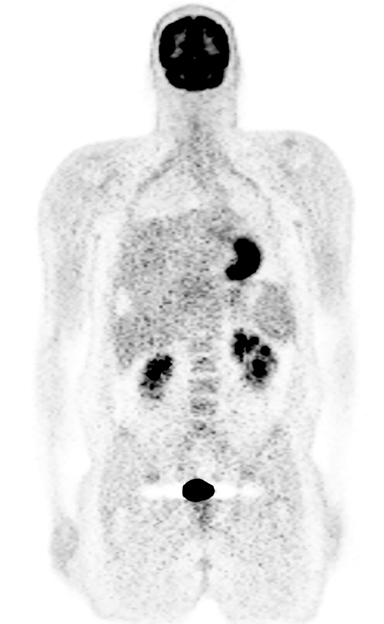

Initial PA and lateral chest X-rays demonstrated apparent elevation of the right hemidiaphragm (Figure 1). A subsequent contrast-enhanced CT scan of the chest demonstrated a heterogeneous, lobulated, hypervascular mass in the right lower hemithorax measuring approximately 18 x 18 x 16 cm (CC, AP, transverse). There was no apparent chest wall or mediastinal invasion and no associated pleural effusion or mediastinal adenopathy was seen. Also, there was no evidence of necrosis or calcification. The mass had a significant systemic arterial supply, primarily from the right inferior phrenic artery. Mass effect resulted in shift of the heart and mediastium to the left (Figures 2). A follow up PET/CT scan demonstrated mild heterogeneous FDG activity within the mass with an SUV of 5.18. No FDG-avid mediastinal or hilar adenopathy was seen and there was no evidence of FDG avid metastasis. Also, there was no evidence of direct chest wall invasion (Figure 3).

Subsequently, the patient underwent a CT-guided transthoracic biopsy followed by complete surgical resection.

DIAGNOSIS

Giant solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura

DISCUSSION

Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura (SFTP) are rare, slow-growing neoplasms, initially described in 1870 by Wagner and further characterized by Klemperer and Rabin in 1931.1,2

The tumor is of unknown etiology and there is no known association with asbestos exposure.3 The incidence is approximately 2.8/100,000 with 800 reported cases to date.2 The peak incidence is in the 5th to 8th decades, with no sex predilection. The giant type of fibrous pleural tumors are defined as occupying greater than 40% of the hemithorax and are especially rare, accounting for less than 5% of pleural neoplasms.4

These tumors are typically benign, slow growing lesions, with malignancy occurring in less than 20% of cases. Previously thought to arise from the mesenchymal of the submesothelial cells of the parietal pleura,5 giant solitary fibrous tumors have now been reclassified by the World Health Organization Classification of Tumors. They are now considered part of a broader class of soft tissue neoplasms of fibroblastic and myofibroblastic origin and can arise from virtually any part of the body.6 The lesions that arise from the pleura are often encapsulated within a thin membrane, which consists of collagen covered by normal mesothelial cells. The tumor is attached to the pleura by a highly vascular pedicle in 38-42% of cases. The base of the tumor is on the visceral pleura in about three quarters of the patients.5 Malignant tumors are often necrotic with hemorrhage, and they may also result in pleural effusion and adjacent structural invasion.7

SFTP are often asymptomatic and tend to present secondary to mass effect on adjacent structures, resulting in nonspecific thoracic symptoms including chest pain, dyspnea, cough, and more rarely hemoptysis. Extrathoracic symptoms have also been reported; these include weakness, fever, weight loss, nocturnal sweating, chills, digital clubbing or hypertrophic osteoarthropathy.3 Hypoglycemia has also been reported related to the production by the tumor of insulin-like growth factor II (IGF-II), which causes an increased glucose utilization and an impaired growth hormone counter-regulatory response to hypoglycemia.8,9

Treatment is based on complete surgical resection, which is curative in nearly all benign lesions and approximately half of malignant ones. Pedunculated tumors can be safely resected with a wedge resection of the lung, but large sessile tumors often require lobectomy or pneumonectomy. Surgical resection, however, is often complicated by the extensive bronchial and systemic arterial supply. In cases involving systemic arterial supply to the tumor, catheter directed embolization may be helpful in reducing the blood supply and risk of perioperative hemorrhage.5 In many cases, the large tumor burden can also result in chronic compressive atelectasis and, therefore, post- operative expansion edema is a known complication.9

The CT appearance of an SFTP is often that of a well-circumscribed lobular homogenous mass often demonstrating marked heterogeneity and necrosis as well as atelectasis and compression/displacement of adjacent structures.4 Pleural effusions are relatively rare, occurring is less than 10% of patients.10

CONCLUSION

Giant solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura are part of a broad class of fibroblastic lesions that can occur nearly anywhere in the body. These relatively rare tumors are often asymptomatic, eventually presenting with symptoms related to mass effect on adjacent structures or occasionally from paraneoplastic phenomena. The imaging features are typical of benign lesions: well circumscribed, without necrosis or local invasion and often have a significant systemic blood supply. This case also highlighted the PET scan findings of mild FDG activity. They are rarely malignant and complete surgical resection is usually curative.

REFERENCES

- Wagner E. Das tuberkelähnliche Lymphadenom (der cytogene oder reticulirte Tuberkel). Arch Heilk (Leipzig) 1870; 11:497.

- Okike N, Bernatz PE, Woolner LB. Localized mesothelioma of the pleura: benign and malignant variants. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1978; 75:363–372.

- Suter M et al, Localized Fibrous Tumours of the Pleura: 15 New Cases and Review of the Literature. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1998;14(5), 453-459.

- Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Abbott GF., Page McAdams H, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura. Radiographics. 2003; 23:759–783. doi: 10.1148/rg.233025165.

- England DM, Hochholzer L, McCarthy MJ. Solitary benign and malignant fibrous tumors of the pleura. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989; 13:640–658. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198908000-00003.

- Galateau-Salle F, Churg A, Roggli V, Travis WD; World Health Organization Committee for Tumors of the Pleura The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Pleura: Advances since the 2004 Classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2016 Feb;11(2):142-54. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.11.005.

- de Perrot M, Fischer S, Bründler MA, Sekine Y, Keshavjee S. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura. Ann Thorac Surg 2002; 74:285–293.

- Masson EA, Mac Farlane IA, Graham D, Foy P. Spontaneous hypo-glycemia due to a pleural fibroma: role of insulin-like growth factors. Thorax. 1991; 46:930–931.

- Juntang Guo, Xiangyang Chu, Yu-e Sun, et al. World J Surg. 2010 Nov; 34(11): 2553–2557.Published online 2010 Jul 14. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0715-x).

- Robinson LA, Reilly RB. Localized pleural mesothelioma. The clinical spectrum. Chest. 1994;106:1611–1615.

Citation

E R, Solomon.Giant solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura. Appl Radiol. 2018; (9):41-43.

September 22, 2018