Cystic Lesions of the Head and Neck: Benign or Malignant? Part 2

Images

Editor’s note: This is the second part of a two-part series. Part 1 appeared in the September/October 2020 issue of Applied Radiology.

Cystic head and neck lesions run the gamut in severity from incidental to life-threatening. Diagnostic specificity can be improved by identifying the involved anatomical spaces and correlating with a detailed clinical history.

Part 1 of this article series discussed differential diagnoses for lesions in the oral cavity, pharynx, masticator space, and parotid space. Here, we explore lesions of the carotid space and associated lymph nodes, retropharyngeal space, prevertebral space, visceral space, and supraclavicular fossa.

Carotid Space and Internal Jugular Chain Lymph Nodes

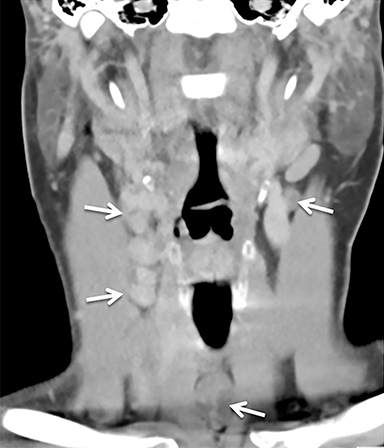

The carotid space extends from the aortic arch to the skull base, just lateral to the retropharyngeal space; it contains primarily the common carotid artery, internal carotid artery (ICA), internal jugular vein (IJV), and portions of cranial nerves 9-12 (Figure 1).

These components are enveloped by the carotid sheath, which defines the boundaries of the space. Important structures closely associated with the carotid space and lying along the outer surface of the carotid sheath, include the sympathetic trunk (chain) and the internal jugular (deep cervical) chain lymph nodes.1

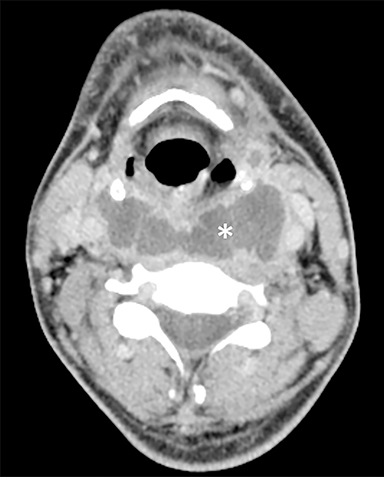

The most common cystic lesions within or associated with the carotid space are necrotic or suppurative lymph nodes. The term “necrotic” implies metastatic disease and “suppurative” implies infection (ie, an intranodal abscess), but their imaging features can be very similar. Associated inflammatory changes favor infection, often related to periodontal disease or pharyngitis. However, metastatic disease should always be the primary concern in adults, especially in the absence of signs or symptoms of infection.2

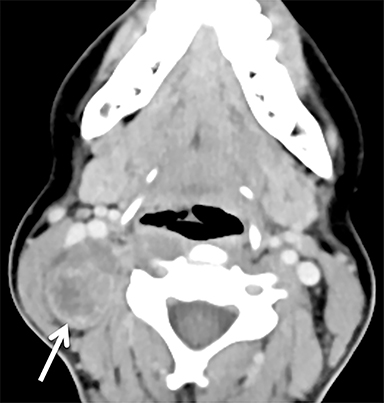

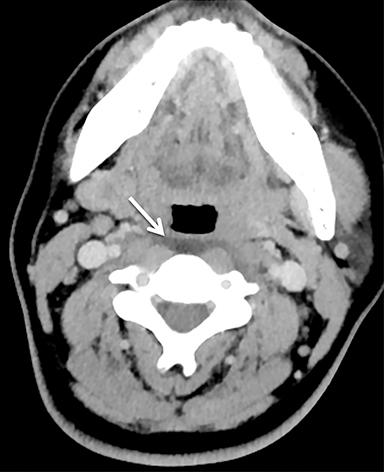

The primary tumor will most likely be a squamous cell carcinoma arising from the pharynx. Less commonly, cervical lymphadenopathy with cystic and partially calcified nodes in a young woman is strongly suggestive of papillary thyroid cancer (Figure 2).3 In both cases, the primary tumor may be small and difficult to identify without a high index of suspicion. Of note, tuberculosis can mimic metastatic disease and also should be considered in cases involving risk factors such as HIV, intravenous drug use, or time spent in areas with high rates of tuberculosis.4

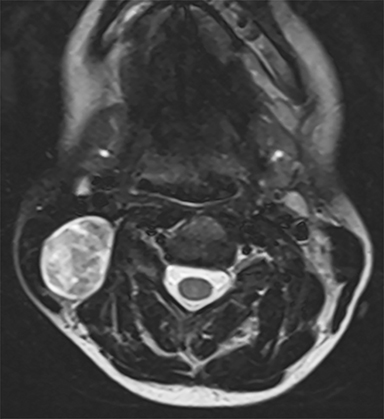

Another mass occasionally seen in the carotid space is a schwannoma, most commonly arising from the vagus nerve. Like most masses in the carotid space, schwannomas are typically solid, but larger schwannomas can demonstrate non-enhancing cystic areas (Figure 3).5 A vagal schwannoma characteristically appears as a fusiform enhancing mass that splays the ICA and IJV.6 A schwannoma arising from the sympathetic chain is more likely to displace the ICA and IJV anteriorly, although splaying of the carotid bifurcation, a finding typically associated with a carotid body paraganglioma, has also been described.7 On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), however, schwannomas lack the flow voids characteristic of paragangliomas.8

Retropharyngeal and Prevertebral Spaces

The retropharyngeal space lies posterior to the pharynx and esophagus and contains only the retropharyngeal lymph nodes (adjacent to the nasopharynx) and fat (Figure 1). The prevertebral space lies posterior to the retropharyngeal space and contains the vertebral bodies, longus colli and capitis muscles, scalene muscles, roots of the brachial plexus, and the vertebral artery and vein (Figure 1).1

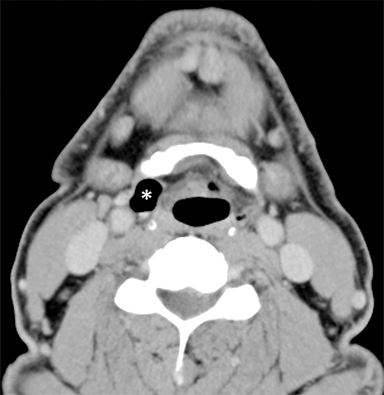

Cystic lesions in these spaces comprise a fairly short differential diagnosis. An enlarged cystic retropharyngeal node may represent metastatic disease (most commonly from nasopharyngeal carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma) or, in younger patients, a suppurative node related to a pharyngeal infection.2 A more diffuse fluid collection between the pharynx/esophagus and vertebral body represents either retropharyngeal edema or an abscess (retropharyngeal and/or prevertebral). The distinction is critical: a retropharyngeal abscess is a serious condition requiring urgent otolaryngology consultation and possible surgical drainage, whereas retropharyngeal edema resolves spontaneously when the cause is treated.9

A retropharyngeal abscess typically appears as a large retropharyngeal fluid collection with rounded margins, pronounced mass effect, and rim enhancement (Figure 4).9 The source of the infection may be a ruptured, suppurative retropharyngeal node or a penetrating foreign body. In older patients, ventral extension of prevertebral abscess associated with discitis/osteomyelitis is more likely. Another consideration is a mediastinal infection that has spread superiorly along the retropharyngeal “danger space.”

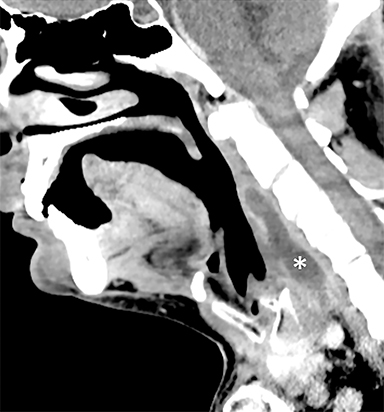

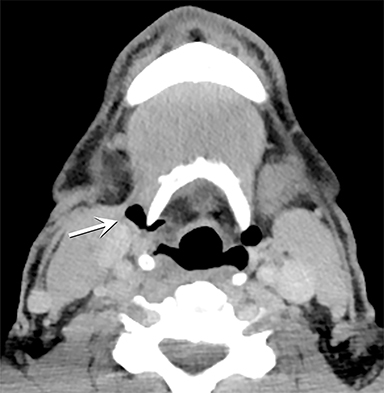

Retropharyngeal edema has more benign imaging features, with tapered inferior and superior margins, minimal mass effect, and no rim enhancement (Figure 5).9 There are multiple etiologies, including recent radiation therapy, IJV thrombosis, pharyngeal infection, and longus colli calcific tendinitis. Longus colli calcific tendinitis is an uncommon inflammatory reaction to calcium hydroxyapatite deposition in the longus colli tendons, and is characterized by amorphous prevertebral calcifications at the level of C1-C2, along with mild retropharyngeal edema.10 Diagnosing this condition can be particularly helpful because, while its clinical presentation can mimic a serious infection, the condition resolves with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory treatment.11

Visceral Space

The visceral space is the midline anterior space extending from the hyoid bone to the superior mediastinum and containing the larynx and trachea, hypopharynx and cervical esophagus, thyroid and parathyroid glands, recurrent laryngeal nerves, and lymph nodes (Figure 6).1

The differential diagnosis for a cystic lesion in this space depends on the organ. In the larynx, the most frequently seen cystic lesion is a laryngocele, a dilated laryngeal saccule (lateral and superior to the glottis) containing fluid or air. An internal (or simple) laryngocele is confined to the paraglottic space; a mixed (or external) laryngocele extends through the thyrohyoid membrane into the submandibular space (Figure 7).12

Another air-filled outpouching, the tracheal diverticulum, is often found incidentally at the right posterolateral aspect of the trachea near the thoracic inlet (Figure 8).13 Laryngoceles and tracheal diverticula are associated with chronic cough and other causes of increased airway pressure.

At the junction of the hypopharynx and esophagus, the Zenker diverticulum and the less common Killian-Jamieson diverticulum may have a narrow neck with a cystic appearance, containing trapped ingested debris and air. Best evaluated with a barium swallow, these outpouchings can be distinguished by their orientation: a Zenker diverticulum protrudes posteriorly at the midline, while a Killian-Jamieson diverticulum is usually unilateral and left-sided.14,15

A cystic nodule in the thyroid is usually incidental and benign (eg, a colloid cyst). Most thyroid nodules found on CT, whether solid or cystic, are better evaluated with ultrasound if they meet criteria for further imaging work-up.16 Cystic, almost completely cystic, or spongiform nodules on ultrasound are considered benign and assigned zero points using the Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (TI-RADS).17 At the opposite end of the clinical/imaging spectrum, a large, heterogeneous, invasive cystic and solid mass centered in the thyroid gland in an elderly patient is the classic imaging presentation of an anaplastic thyroid carcinoma.18 In younger patients, a thyroid or anterior cervical abscess is more likely, especially if they are immunocompromised (Figure 9).19

Outside of the organs, the most important lesion in the visceral space is the thyroglossal duct cyst. A developmental remnant of the thyroglossal duct, this congenital lesion can occur anywhere along the duct from the base of the tongue to the thyroid gland, but it is most frequently located at or near the midline anterior to the thyroid cartilage.12 The typical appearance is that of a circumscribed, thin-walled, fluid-density cyst that may show rim enhancement in the setting of inflammation or infection.20 On MRI, the fluid often demonstrates T1 hyperintensity related to hemorrhage or proteinaceous contents.21 Rarely, a thyroglossal duct carcinoma can arise within the cyst, suggested by the presence of a solid nodule or calcification (Figure 10).22 Most thyroglossal duct cysts present clinically in childhood.20

Supraclavicular Fossa

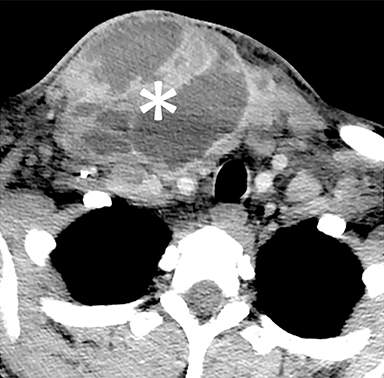

Two lesions in the supraclavicular fossa deserve special mention: the necrotic left supraclavicular lymph node and the much less common lymphocele. A left supraclavicular lymph node (or Virchow node) that is enlarged, with or without central necrosis, is strongly suggestive of metastatic disease, especially from a primary tumor in the abdomen (Figure 11).23

In contrast, a lymphocele (or lymphatic cyst) is benign and usually incidental, with the imaging features of a simple cyst or fluid collection. Lymphoceles are most commonly found in the left supraclavicular fossa, where both the thoracic duct and cervical lymphatic duct drain into the confluence of the left subclavian vein and IJV. Often the cysts are sequelae of prior surgery or trauma. No further work-up is required unless atypical features such as enhancement or a solid component are present.24

Conclusion

A remarkable variety of cystic lesions, including congenital and acquired cysts, simple and complex fluid collections, and benign and malignant masses, are encountered in the neck and oral cavity. Knowledge of anatomical spaces, other helpful imaging features, and patient history can improve diagnostic accuracy and clinical management.

References

- Koch BL, Hamilton BE, Hudgins PA, Harnsberger HR. Diagnostic imaging. Head and neck. Third edition. ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017.

- Fang WS, Wiggins RH, Illner A, et al. Primary lesions of the root of the tongue. Radiographics. 2011;31(7):1907-1922.

- Ozturk M, Mavili E, Erdogan N, Cagli S, Guney E. Tongue abscesses: MR imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27(6):1300-1303.

- Srivanitchapoom C, Yata K. Lingual Abscess: Predisposing Factors, Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Management. Int J Otolaryngol. 2018;2018:4504270.

- Wong KT, Lee YY, King AD, Ahuja AT. Imaging of cystic or cyst-like neck masses. Clin Radiol. 2008;63(6):613-622.

- Patel S, Bhatt AA. Imaging of the sublingual and submandibular spaces. Insights Imaging. 2018;9(3):391-401.

- Dillon JR, Avillo AJ, Nelson BL. Dermoid Cyst of the Floor of the Mouth. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9(3):376-378.

- La’porte SJ, Juttla JK, Lingam RK. Imaging the floor of the mouth and the sublingual space. Radiographics. 2011;31(5):1215-1230.

- Koontz N, Kralik S, Fritsch M, Mosier K. MR siaolography: a pictorial review. Neurographics. 2014;4(3):142-157.

- Lee JY, Lee HY, Kim HJ, et al. Plunging Ranulas Revisited: A CT Study with Emphasis on a Defect of the Mylohyoid Muscle as the Primary Route of Lesion Propagation. Korean J Radiol. 2016;17(2):264-270.

- Kurabayashi T, Ida M, Yasumoto M, et al. MRI of ranulas. Neuroradiology. 2000;42(12):917-922.

- Coit WE, Harnsberger HR, Osborn AG, Smoker WR, Stevens MH, Lufkin RB. Ranulas and their mimics: CT evaluation. Radiology. 1987;163(1):211-216.

- Wassef M, Blei F, Adams D, et al. Vascular Anomalies Classification: Recommendations From the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):e203-214.

- Meesa IR, Srinivasan A. Imaging of the oral cavity. Radiol Clin North Am. 2015;53(1):99-114.

- Gaddikeri S, Vattoth S, Gaddikeri RS, et al. Congenital cystic neck masses: embryology and imaging appearances, with clinicopathological correlation. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2014;43(2):55-67.

- Capps EF, Kinsella JJ, Gupta M, Bhatki AM, Opatowsky MJ. Emergency imaging assessment of acute, nontraumatic conditions of the head and neck. Radiographics. 2010;30(5):1335-1352.

- Ali SA, Kovatch KJ, Smith J, et al. Predictors of intratonsillar versus peritonsillar abscess: A case-control series. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(6):1354-1359.

- Viens LJ, Henley SJ, Watson M, et al. Human Papillomavirus-Associated Cancers - United States, 2008-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(26):661-666.

- Hudgins PA, Gillison M. Second branchial cleft cyst: not!! AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(9):1628-1629.

- Kuan EC, Mallen-St Clair J, St John MA. Evaluation of Parotid Lesions. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2016;49(2):313-325.

- Yousem DM, Kraut MA, Chalian AA. Major salivary gland imaging. Radiology. 2000;216(1):19-29.

- Hamilton BE, Salzman KL, Wiggins RH, Harnsberger HR. Earring lesions of the parotid tail. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(9):1757-1764.

- Kessler AT, Bhatt AA. Review of the Major and Minor Salivary Glands, Part 2: Neoplasms and Tumor-like Lesions. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2018; 8:48.

- Christe A, Waldherr C, Hallett R, Zbaeren P, Thoeny H. MR imaging of parotid tumors: typical lesion characteristics in MR imaging improve discrimination between benign and malignant disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32(7): 1202-1207.

- Carlson ER, Webb DE. The diagnosis and management of parotid disease. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2013;25(1):31-48.

Citation

B W, III WR.Cystic Lesions of the Head and Neck: Benign or Malignant? Part 2. Appl Radiol. 2020; (6):23-30.

November 6, 2020