Button battery ingestions and diagnostic imaging

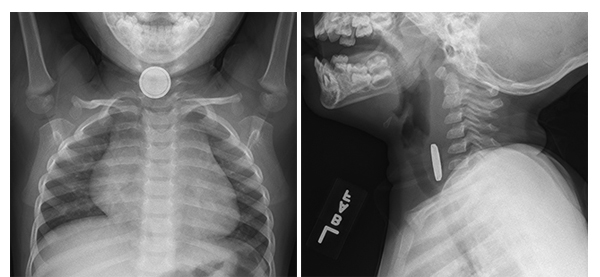

Frontal and lateral radiograph in a 20-month-old boy who swallowed a button battery show the battery,

which appears as a discoid metallic density with a beveled edge, at the level of the cervical esophagus.

There is soft tissue thickening between the battery and the tracheal air column on the lateral view

reflective of soft tissue swelling. This battery was retrieved by endoscopy more than four hours after

reported ingestion. Severe (grade 3), circumferential mucosal injury was present at the time of retrieval.

Children have been swallowing disc-shaped button batteries for decades, but injuries from these have been on the increase in the United States. The steady increase is attributed to the use of lithium cell batteries and batteries with larger diameters.

Radiography is the recommended modality for initial diagnosis and localization of an ingested battery. However, recent guidelines from the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) recommend that chest CT angiography or chest MRI be performed for battery removal on patients with any esophageal injury seen on endoscopy.1 Physicians at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center conducted a retrospective study to catalog imaging features of button battery ingestion and to assess the impact the NASPGHAN guidelines might have.

A team of pediatric radiologists, gastroenterologists, and otolaryngologists identified 276 children during a 15-year period who had received treatment including imaging exams after swallowing button batteries. Their retrospective review focused on imaging aspects of these cases.

The children ranged in age from 9 months to 16 years, although the majority of patients were boys and under the age of five. Data collection included determining the size and location of the battery and battery anode, types and quantity of imaging exams performed and findings, time from ingestion to endoscopic retrieval, findings at endoscopy, and clinical complications.

The majority of batteries (60%) were between 10 and 15 mm in diameter, but 20% were 20 mm or larger. Ingested batteries were located in the stomach (61.5%), the esophagus (9.8%), and the colon (8.7%). Batteries located in the esophagus were significantly larger than those that had passed distally. The most common site of esophageal impaction was the distal esophagus, with one-third of batteries lodging in the vicinity of the aortic arch. Only 22 patients had battery erosions apparent on radiography. Five patients, four of whom were younger than three years of age, had major clinical complications.

Radiologist Andrew T. Trout, MD, and colleagues reported that the size of an ingested battery was significantly associated with severity of esophageal injuries that were grade 1 or higher mucosal injury. In fact, all patients with grade 1 or higher mucosal injury had swallowed batteries that were greater than 20 mm in diameter. There was no statistically significant difference between the degree of mucosal injury and whether the battery was located in the proximal or distal esophagus. Additionally, 16% of patients with a battery in the stomach at the time of imaging had esophageal mucosal injury. Interestingly, the length of time between ingestion and retrieval had no statistically significant impact on the severity of mucosal injury.

Radiographic findings of possible complications — specifically soft-tissue swelling and tracheal air column narrowing — were identified in only four patients, but those patients had the most severe grade of mucosal injury. The authors noted that radiographs are insensitive to mucosal injury related to button battery ingestion.

Nineteen patients (6.9% of the total) underwent fluoroscopy and four patients had CT scans (1.4% of the total). Eleven of these patients had mucosal injury on endoscopy. More than one third of the patients had follow-up radiographs. These were patients who were managed conservatively and did not undergo endoscopy.

The authors estimated that conservatively at least 25 of the patients in their series would have undergone chest CT scans or MRI based on the NASPHGAN guidelines. This would have represented an eight-fold increase in the use of chest CT or MRI.

“Implementation of the proposed guidelines from NASPGHAN, which recommend considering chest CT angiography or chest MRI for patients with any esophageal injury seen on endoscopy, would result in a substantial increase in the number of CT examinations performed in patients like ours…..Perhaps a recommendation of advanced chest imaging for all patients with any degree of esophageal injury may be too broad and a more nuanced approach may be appropriate,” they commented. They recommended that radiologists continue to assess the impact of the NASPGHAN guidelines.

REFERENCES

- Kramer RE, Lerner DG, Lin T, et al. Management of ingested foreign bodies in children: a clinical report of the NASPGHAN Endoscopy Committee. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015. 60;4:562-574.

- Pugmire BS, Lin TK, Pentiuk S, et al. Imaging button battery ingestions and insertions in children: A 15-year single-center review. Pediatr Radiol. 2016

Citation

. Button battery ingestions and diagnostic imaging. Appl Radiol.

February 1, 2017