Abdominal CSF pseudocyst

Images

Abdominal CSF pseudocyst

Findings

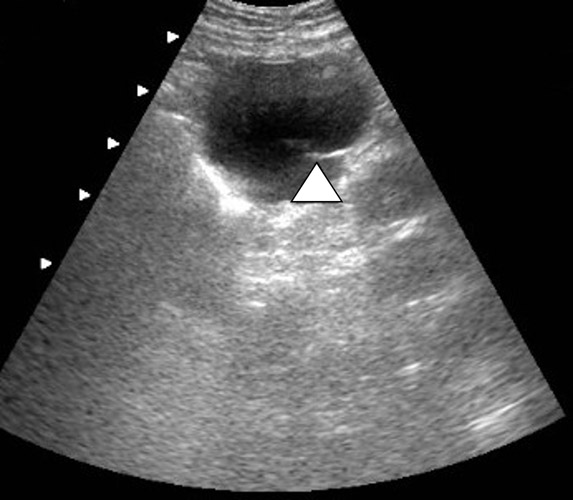

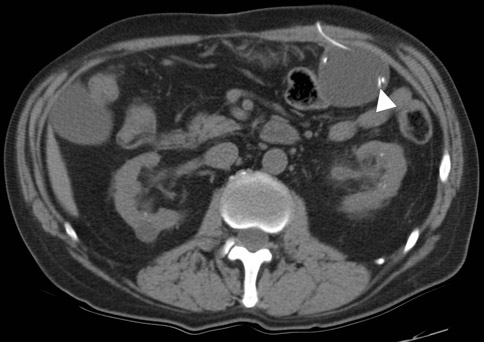

The supine abdominal radiograph showed a subtle soft-tissue–density mass around the ventriculoperitoneal shunt tip. Ultrasound of the left upper quadrant of the abdomen showed an approximately 5 cm rounded cystic mass with the tip of the ventriculoperitoneal shunt within the collection. CT also demonstrated a cystic mass in close association with the ventriculoperitoneal shunt with the tip of the shunt lying within the collection. The patient underwent ultrasound-guided percutaneous aspiration of the pseudocyst with relief of symptoms.

A 62-year-old patient presented with dull abdominal pain and palpable fullness in the left mid abdomen for several days. His past medical history was significant for a ruptured PICA aneurysm 2 years ago, which had been treated with clipping of the aneurysm anda ventriculoperitoneal shunt for hydrocephalus. Abdominal radiography, ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) scans were obtained (Figures 1–3).

Discussion

The use of the peritoneal cavity for CSF absorption in ventriculoperitoneal shunting is standard care in the management of hydrocephalus. The most common extracranial complications of ventriculoperitoneal shunt are tube disconnection, blockage of the shunt tip, infection, bowel obstruction and perforation.1 Uncommon complications described in the literature include subphrenic abscess, small-bowel perforation with secondary formation of a cerebrospinal-enteric fistula, untreatable CSF ascites, migration of the shunt tip to distant locations such as the intrathoracic or subphrenic areas, protrusion of the shunt from the anus and pseudocyst formation.2 Peritoneal pseudocyst formation is a rare complication of ventriculoperitoneal shunt. The first periumbilical pseudocyst was described by Harshin in 19543 and a frequency of 1% to 4.5% pseudocyst formation since then has been reported in the literature. The time period from the last shunting procedure to the development of an abdominal pseudocyst usually ranges from 3 weeks to 5 years.4

Predisposing factors to CSF pseudocyst formation seem to be related to inflammatory processes such as infection, peritoneal adhesions from previous surgery, multiple shunt revisions, increased CSF proteins, malabsorption of CSF secondary to subclinical peritonitis and anallergic or nonspecific inflammatory response to the peritoneal catheter or to a component of the CSF.5

Histologically the wall of the pseudocyst is composed of fibrous tissue without epithelial lining and is filled with CSF. Ultrasound and CT can confirm the diagnosis. Ultrasound shows a well-defined lucent mass with posterior acoustic enhancement. A noninfected cyst will show uniform internal echotexture and septa that often occur in an infected pseudocyst. CT shows a cyst containing homogeneous water-density fluid. It is important to identify the shunt tip within the cyst for confident diagnosis.

A nuclear medicine study can also help in detecting abdominal CSF pseudocysts. Radioisotopes injected into the shunt reservoir should normally distribute freely through the abdomen. Therefore, loculation of the radioactive tracer within an abdominal collection suggests pseudocyst formation.6 The differential diagnosis of an abdominal cystic mass includes mesenteric cyst, duplication cyst, pancreatic pseudocyst, lymphocele, seroma, cystic lymphangioma, mesenteric abscess, benign cystic teratoma, and cystic spindle cell tumor. The appropriate clinical setting and an intimate relationship of the cystic mass to the ventriculoperitoneal shunt help in suggesting CSF pseudocyst as the most likely diagnosis. Percutaneous aspiration/drainage of the pseudocyst can be both diagnostic and therapeutic. If infection is present, the pseudocyst should be excised and the shunt tube should be removed.7

Conclusion

Abdominal CSF pseudocyst formation is a rare, but well-recognized complication of ventriculoperitoneal shunting. Identifying the tip of the shunt within the cyst on radiological studies helps in making the confident diagnosis.

- Murtagh FR, Quencer RM, Poole CA. Extracranial complications of cerebrospinal fluid shunt function in childhood hydrocephalus. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1980;135:763-766.

- Agha FP, Amendola MA, Shirazi KK, et al. Unusual abdominal complications of ventriculo-peritoneal shunts. Radiology. 1983;146:323-326.

- Harsh GR 3rd. Peritoneal shunt for hydrocephalus, utilizing the fimbria of the fallopian tube for entrance to the peritoneal cavity. J Neurosurg. 1954;11:284-294.

- Ersahin Y, Mutluer S, Tekeli G. Abdominal cerebrospinal fluid pseudocysts. Childs Nerv Syst. 1996;12:755-758.

- Rovlias A, Kotsou S. Giant abdominal CSF pseudocyst in an adult patient 10 years after a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt. Br J Neurosurg. 2001;15: 191-192.

- Eschelman DJ, Lee VW. Lesser sac cerebrospinal fluid collection, an unusual complication of ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Clin Nucl Med. 1990;15(6):415-417.

- Pernas JC, Catala J. Case 72: Pseudocyst around ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Radiology. 2004;232:239-243.