Vaginal Cuff Dehiscence and Small-Bowel Evisceration (VCDE)

Images

Case Summary

A middle-aged woman presented to the emergency department with a chief complaint of sudden onset excruciating epigastric pain, followed by diarrhea and visible vaginal bulge. Pertinent history included breast cancer diagnosed 15 months prior, with subsequent bilateral mastectomy, radiation, chemotherapy, and then robotic-assisted prophylactic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophrectomy six months prior. Relevant additional history included tobacco use, obesity, and first postoperative coitus two days prior. In the ED, pelvic organ prolapse was diagnosed, which was reduced, leading to a reduction in the patient’s pain.

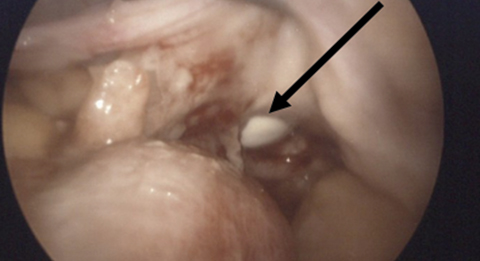

Subsequent examination revealed an abdomen tender to palpation. Vaginal exam displayed no pelvic organ prolapse however bowel was visible at the vaginal cuff, with clear yellow fluid pooling in the vaginal vault. The patient’s white blood cell count increased from 6.0 to 10.3 K/uL over 24 hours. A 4-cm vaginal cuff defect was identified during exploratory laparoscopy (Figure 1), and transvaginal cuff closure was performed.

Imaging Findings

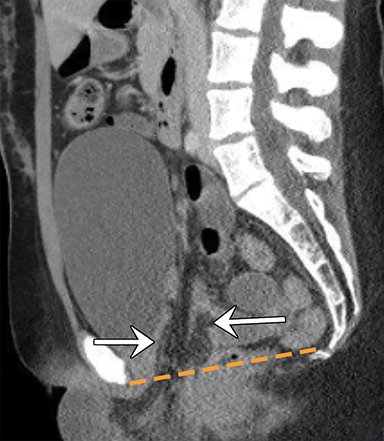

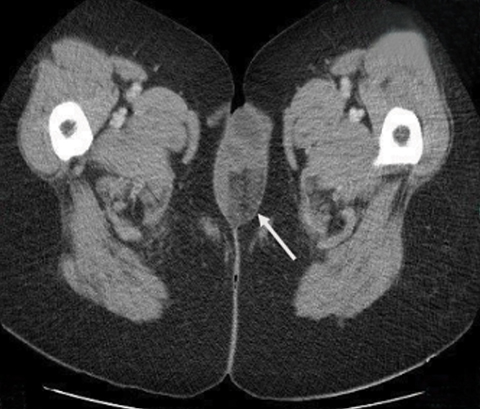

A CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis (Figures 2-5) revealed several loops of small-bowel and mesenteric fat coursing through a defect in the expected location of the vagina. Small-bowel loops were noted external to the patient and located between the labia. Micro-pneumoperitoneum was identified.

Diagnosis

Vaginal cuff dehiscence and small-bowel evisceration (VCDE). Differential diagnoses include pelvic organ prolapse and enterocele, small-bowel strangulation, and vesicovaginal fistula.

Discussion

Post-hysterectomy vaginal cuff dehiscence occurs at a rate of 0.14 - 4.1%,1,3 and with associated evisceration at a rate of 0.032 - 1.2%.2,3 The small bowel is the most commonly prolapsed organ; complications, including bowel necrosis, result in a bowel resection rate of up to 20%.4 Since pelvic organ prolapse and VCDE may appear radiologically similar, an elevated and increasing WBC count, acute onset vaginal protrusion, and severe abdominal pain may help distinguish between the entities.

With careful inspection, CT can distinguish pelvic organ prolapse, including enterocele, from VCDE. Important to note on CT are pelvic floor instability, specifically in the perineal body, and the location of the bladder. Coronal CT views may lead to inaccurate diagnosis, as the perineal body and pelvic floor stability cannot be optimally visualized. As a result, a sagittal view is recommended to distinguish VCDE from prolapse.

In premenopausal women, VCDE is rare and most frequently associated with vaginal trauma associated with early resumption of coitus, gynecological instrumentation, or foreign body insertion.5 In addition, most episodes of intercourse-precipitated vaginal cuff dehiscence occur within four postoperative months.1,2 This was an unusual case of a young, surgically postmenopausal woman who waited what would be considered an appropriate length of time to resume coitus. Her risk factors for VCDE included possible reduced tissue quality secondary to chemotherapy, hypoestrogenism, tobacco use, and obesity.

A delay in diagnosing VCDE can lead to peritonitis, cuff inflammation, adhesions, and distortion of tissue planes, complicating dissection of the surrounding bowel and bladder, and repair of the cuff.6 This case illustrates that radiologists and clinicians must remain cognizant of the possibility of VCDE, as prompt management is critical for preserving the eviscerated organ and obtaining optimal patient outcomes.

Conclusion

Sudden onset visible vaginal bulge accompanied by abdominal pain and diarrhea in a patient with a history of hysterectomy is suggestive of VCDE. Although vaginal cuff dehiscence and evisceration is a less common radiological finding than pelvic floor instability and prolapse, radiologists should consider VCDE when imaging is suggestive of pelvic organ prolapse. Inaccurate interpretation may lead to potentially harmful maneuvers, such as attempted reduction of an eviscerated small bowel. In addition, the history of presenting illness can help guide radiologists when the imaging features may not be as clear.

References

- Hur HC, Guido RS, Mansuria SM, Hacker MR, Sanfilippo JS, Lee TT. Incidence and patient characteristics of vaginal cuff dehiscence after different modes of hysterectomies. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:311–317.

- Nezhat C, Kennedy Burns M, Wood M, Nezhat C, Nezhat A, Nezhat F. Vaginal cuff dehiscence and evisceration. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(4):972‐985.

- Kho RM, Akl MN, Cornella JL, Magtibay PM, Wechter ME, Magrina JF. Incidence and characteristics of patients with vaginal cuff dehiscence after robotic procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:231–235.

- Ramirez PT, Klemer DP. Vaginal evisceration after hysterectomy: a literature review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2002;57:462–467.

- Cardosi RJ, Hoffman MS, Roberts WS, Spellacy WN. Vaginal evisceration after hysterectomy in premenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:859.

- Hur HC, Lightfoot M, McMillin MG, Kho KA. Vaginal cuff dehiscence and evisceration: a review of the literature. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;28:297–303.

References

Citation

A N, L K, S N.Vaginal Cuff Dehiscence and Small-Bowel Evisceration (VCDE). Appl Radiol. 2021; (4):50-52.

July 15, 2021