Technology Trends: Calling in reinforcements—Women with dense breasts get help from ultrasound, molecular imaging, and MRI

Images

For the past 30 years, mammography has been the standard of care for screening women for breast cancer. However, it often fails to pick up lesions when used to image a particular patient population—the approximate 40% to 50% of women with dense breasts.

The facts surrounding dense breasts should be an eye-opener for women, their physicians, and radiologists alike. In addition to their prevalence in nearly half of women, dense breasts are a strong predictor of breast cancer risk, even greater than having two first-degree relatives with a history of breast cancer. That dense breasts mask cancer in mammography—which misses, on average, every other cancer—further compounds the clinical effectiveness of this modality as an accurate screening modality.

With the heightened focus on imaging women with dense breasts, interest is growing as well in other breast imaging modalities, including ultrasound—automated and elastrography—molecular breast imaging (MBI) and MRI.

Breast elastography

Breast elastography is a sonographic technique that provides information on the strain or hardness of a lesion. Compression strain elastography evaluates how a tissue deforms when compression is applied to it, while shear wave elastography maps the elasticity of soft tissue and provides a value for the relative stiffness of the tissue.

Richard G. Barr, MD, PhD, FACR, FSRU, Professor of Radiology at Northeastern Ohio Medical University and Radiology Consultants, Inc. (Youngstown, OH), believes strongly in breast ultrasound as an adjunct to mammography and has published several studies and articles on breast elastography. Dr. Barr has also written a book, scheduled to be published later this year, on breast ultrasound elastography covering pathology, patterns of cancer, and characterizing lesions found with elastography.

During the last five years, Dr. Barr has used elastography—both strain and shear wave—in every breast ultrasound exam, whether as part of a clinical study or in clinical practice. Dr. Barr and his colleagues also participated in the ACRIN 6666 study, which is currently pending publication (in press).

“We believe in ultrasound screening in women with dense breasts and we’ve had very good results,” Dr. Barr says. “Using breast ultrasound elastrography, we can characterize a breast mass as benign or malignant with a sensitivity that is now about 99% and specificity is approximately 90%.”

In his practice, the standard protocol is to use automated breast ultrasound on women with a negative mammogram and a breast density of 3 or 4. This is helping to find between six and eight cancers per thousand patients—lesions not picked up by mammography alone. Those patients are then brought back for handheld ultrasound with elastography, both strain and shear wave.

“With strain elastrography, there is an interesting phenomenon where a malignant lesion appears larger than on conventional ultrasound, and a benign lesion appears smaller,” Dr. Barr explains. “The only cancers missed with strain elastrography are lymphomas in the breast. These are soft lesions, so unfortunately the elastography is correct (in terms of tissue stiffness).

“In shear imaging, we’ve also had good results,” he continues. “If our results are concordant between strain and shear wave, then we have a high confidence that a positive result is accurate.” In fact, Dr. Barr and his colleagues have used this information to achieve positive biopsy rates approaching 75%. Considering that with mammography 80% of biopsied lesions are benign, Dr. Barr believes that ultrasound can make a dramatic impact on reducing unnecessary biopsies.

Elastography has also helped guide the biopsy. “In one case, what we thought was one lesion on B-mode ultrasound we actually found out was two lesions—one benign and one malignant,” Dr. Barr says. “We could have inadvertently biopsied the benign one without this information.”

Automated breast ultrasound

Marc F. Inciardi, MD, a radiologist at the University of Kansas/Kansas University Medical Center, was a co-investigator participating in the somo•InSIGHT clinical study evaluating automated breast ultrasound (ABUS) with digital ultrasound compared to digital mammography alone. The study, which began in 2009, has since been completed and the scientific paper has been submitted for publication.

“We conducted the second largest ultrasound study ever, and only the second evaluating automated breast ultrasound,” Dr. Inciardi says. Of the nearly 17,000 women participating in the study, Dr. Inciardi and his colleagues at Kansas imaged approximately 1,650 and found three additional cancers undetected by mammography per thousand in women with dense breasts. All detected cancers were invasive and 9 mm or smaller in size. “In our cohort,” he explains, “of the mammographically detected cancers, 25% were DCIS and 75% were invasive. All ultrasound detected cancers were invasive.”

Dr. Inciardi believes the ideal clinical scenario is to offer ABUS concurrently with a mammogram. If a patient has to return for ABUS, it could impact compliance, he explains. In another scenario, if a 2-cm mass is found on mammography and the woman returns for targeted ultrasound, the exam is only focused on that particular area of the breast without scanning the remainder of that breast or the other one.

“If we offer ABUS concurrent with the mammogram, the ABUS can often resolve the mammographic finding as benign, as well as survey both breasts, and therefore the patient doesn’t have to come back, which also reduces callback rates,” Dr. Inciardi says. “These are all potential benefits, particularly as we are all worried about false positives increasing callback rates.” However, he doesn’t recommend ABUS or handheld ultrasound for screening without specific training, as that could increase false positives.

“We are fortunate to be in an era where breast imagers and radiologists have a choice for imaging dense breasts, such as ultrasound, MBI and MRI,” he says. “We are unfortunate that there is not enough data yet to know how to best use these different modalities.”

The molecular side

The last decade has seen the growth and development of molecular breast imaging (MBI). Current implementations consist of dedicated systems and conventional dual-head gamma cameras.

As reported in a 2011 study in Radiology, the sensitivity of MBI is 91% for all cancers, and 100% for invasive cancers. Specificity is 93% when used with mammography, with a false-positive rate of 3% and a recall rate of 7.6%, or 75.8 per 1,000 women.2

Stephen Phillips, MD, FACR, Assistant Professor of Radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College and Director of Breast Imaging and Intervention, has been using MBI since his tenure at Mayo Clinic as a consultant in radiology and clinical researcher. He currently uses the LumaGEM. “In our practice, we use MBI for patients unable to have an MRI, either due to a pacemaker or other implant, or claustrophobia. It also helps us solve the clinical question when there is a palpable mass and the patient has a negative mammogram or ultrasound. We are also using it more for high-risk patient screening.”

While Dr. Phillips doesn’t see MBI replacing screening mammography, he does believe it can be a useful screening tool when combined with a mammogram in high-risk women as defined by the American Cancer Society’s guidelines for women with family history, genetic disposition, or prior radiation therapy for Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

MBI is also useful for monitoring tumor shrinkage from chemotherapy prior to surgery, Dr. Phillips explains. He’s seen several cases at his hospital’s clinic where the patient received MBI at the diagnosis, underwent chemotherapy to shrink the tumor, and then received a second MBI to evaluate the treatment.

“There are certainly instances where it has shown a relatively dramatic response—a significant decrease in the tumor size or even the tumor no longer viable and showing no uptake,” he explains. This is often accompanied by a clinical response, such as not feeling the tumor, which appears to have a good correlation with the molecular response. While MBI is not being used mainstream in this manner, Dr. Phillips does see potential use in the future.

Nathalie Johnson, MD, FACS, a surgical oncologist and medical director of Legacy Cancer Institute, regularly utilizes breast-specific gamma imaging (BSGI), for newly diagnosed cases. Dr. Johnson recently published a study comparing BSGI to MRI and found that BSGI is a cost-effective tool for evaluating dense breast tissue and new diagnoses of cancer. The study reports that BSGI has a sensitivity of 92%, specificity of 73%, PPV of 78%, and NPV of 90%; BSGI was more accurate (82%) than MRI (72%) at a significantly lower cost—BSGI was $850 per patient compared to $3,381 for MRI.3

“In our current economy, we have to look at how we spend our healthcare dollars,” she says. “BSGI is as good as MRI and less expensive. For women with dense breasts, I think it’s a better diagnostic tool.”

BSGI also helps Dr. Johnson with her surgical planning. The views are the same as with mammography—mediolateral-oblique and cranio-caudal—so she can correlate the studies to determine the exact size and location of a lesion. She can also use BSGI to determine if there is multi-centric disease in the breast.

“We may not pick this up with mammography, ultrasound, or even MRI,” she explains. “Approximately 10% of the time, we will pick up additional cancers in the same or opposite breast with BSGI.” Dr. Johnson can also look for multifocal disease with BSGI, which is important as some women receive partial breast irradiation, or treatment only around the tumor site.

She is also a proponent for greater adoption of BSGI and making it available to more patients. “More rural hospitals that may not have the volume or funds for breast MRI can do BSGI and do it well,” she says. As a surgeon, she can read the BSGI scans herself, while with MRI she requires the assistance of a radiologist to read and understand the flow and enhancement.

“There are times when something lights up on BSGI but we can’t see it with ultrasound or mammography, and even the MRI is negative,” Dr. Johnson adds. “The only way we can see it is with the gamma scan.”

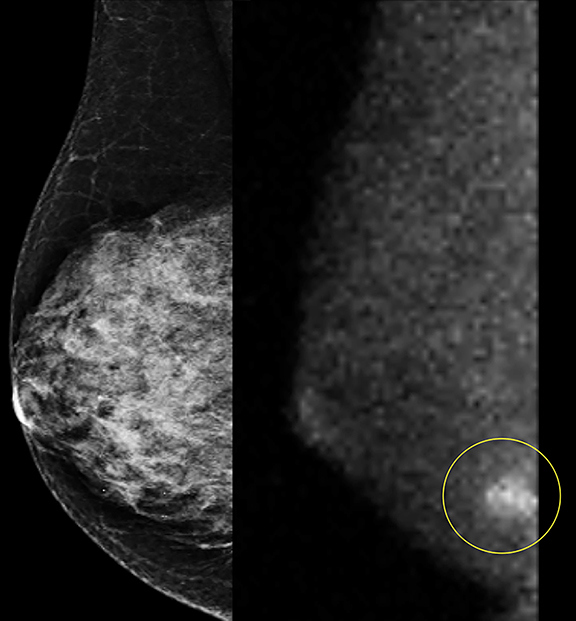

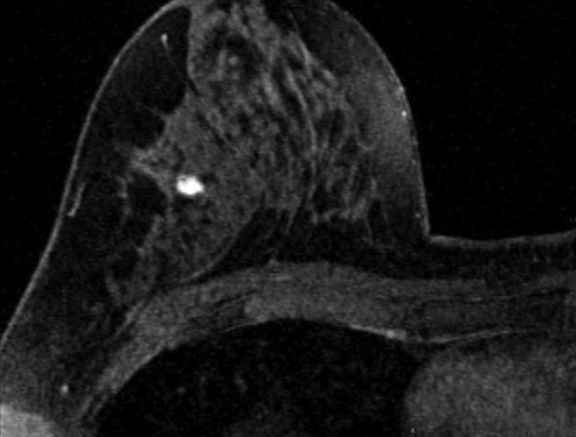

Breast MRI

The ACR recommends MRI for screening high-risk women; the modality has been shown to significantly improve detection of cancers that are clinically, mammographically or sonographically occult.3 However, David A. Strahle, MD, a radiologist and president of the Breast MRI Institute and Regional Medical Imaging (Flint, MI), believes it can play an even greater role as a screening tool.

A common argument against MRI is its cost and its high false-positive rate, which has led to an increase in biopsies. Dr. Strahle’s IRB-approved research, presented at the 2012 RSNA annual meeting and which will be presented again at this year’s RSNA meeting, is helping to eliminate both of these issues.

Dr. Strahle has developed a streamlined breast MRI protocol that uses only three sequences, takes nine minutes to perform and costs under $400. His research started in 2009 when he and his colleagues examined nearly 700 women with breast MRI who had a negative or benign screening mammogram. This initial study found six additional cancers missed by mammography. Just as important, the study also found hundreds of benign lesions also not visualized on the mammograms, supporting the overall inaccuracy of mammograms in women with dense breast tissue.

Throughout his research, Dr. Strahle recorded 18 parameters on each patient after using a full breast MRI study and found three sequences that identified all the cancerous lesions and most of the benign lesions all hidden by dense tissue. By using these three sequences in his clinical practice, Dr. Strahle says he has reduced the time and the cost of screening breast MRI as well as reduced the biopsy rate by half. Nationwide, 8 of 10 biopsies based on mammography are benign; using Dr. Strahle’s MRI protocols, only 5 of 10 biopsies are benign. Since September 2012, Dr. Strahle and his colleagues have been screening women using the abridged protocol for MRI.

“We found super-early breast cancers up to six years earlier than mammography or tomosynthesis,” Dr. Strahle says. “Using MRI to create an initial baseline study, just as we do for mammography, we compare MRI to MRI which increases accuracy even higher. In addition, using MRI baseline studies we believe we can reduce the biopsy rate even further.”

“Mammography alone, when used on the appropriate person, is quite good” he continues, “but only once their breast tissue involutes below 50% fibroglandular tissue by volume.”

In women with dense fibroglandular tissue, Dr. Strahle explains, the sensitivity of mammography can drop to as low as 14%. He also believes tomosynthesis, while better than 2D mammography, will provide only incremental increases.

Dr. Strahle has taken his fight to promote the use of MRI for breast cancer screening to insurance companies in Michigan. Beginning last November, HealthFirst in Michigan began reimbursing for breast MRI screening in addition to mammography in women with over 50% fibroglandular tissue based on volume. In Michigan, the difference in cost between screening mammography and breast MRI using Dr. Strahle’s protocol is, on average, only $72.

“The real advantage is the number of lives saved,” he says, “but by finding cancers super-early, we can also help patients and insurance companies save money in 10 major financial categories that far exceeds the $72 by several multiples.” Many women won’t need to undergo the aggressive treatments required for larger growths or when the cancer spreads, such as to the lymph nodes, Dr. Strahle explains—for example, surgery, chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy.

Dr. Strahle believes that many other facilities are well positioned to provide screening breast MRI, as approximately 30% to 40% of MR systems are underutilized, he says. “We estimate that of all the women with dense breast tissue who could benefit from this procedure, 60% to 65% could be handled right now on existing systems.”

In his opinion, the best way to approach screening for women with dense breasts is to use MRI. “We need to use our best, most powerful weapon in this fight against breast cancer, and that clearly is MRI.”

References

- Friedewald SM, Rafferty EA, Rose SL, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis in combination with digital mammography. JAMA. June 25, 2014.

- Rhodes DJ, Hruska CB, Phillips SW, et al. Dedicated Dual-Head Gamma Imaging for Breast Cancer Screening in Women with Mammographically Dense Breasts. Radiology. 2011;258(1):106-118.

- Johnson N, Sorensen L, Bennetts L, et al. Breast-specific gamma imaging is a cost effective and efficacious imaging modality when compared with MRI. Am J Surg, May 2014; 207(5):698-701.

- ACR practice guideline for the performance of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the breast. Revised 2013. Accessed August 4 2014. Available at: http://www.acr.org/~/media/2a0eb28eb59041e2825179afb72ef624.pdf.

Citation

Technology Trends: Calling in reinforcements—Women with dense breasts get help from ultrasound, molecular imaging, and MRI. Appl Radiol.

September 5, 2014