Pediatric Skull Fracture Without Mechanism

Images

CASE SUMMARY

An 11-month-old female presented with a soft swelling on the right, posterior-parietal region of her head that was noticed 2 days prior.There was no reported history of trauma, fever, vomiting, fatigue, bleeding/bruising, or any associated symptoms. Physical exam revealed a well-appearing and nourished child. Appropriate parental interaction was noted for the child’s age. The head appeared atraumatic and normocephalic with a 4 × 5 cm soft, fluctuant area over the parietal region. There was no depression or erythema. The remainder of the exam, with special attention given to the eyes, ears, nose, throat, and cranial nerves, was grossly normal. Laboratory values were clinically not significant. Ultrasound examination was performed to evaluate the palpable soft tissue swelling.

IMAGING FINDINGS

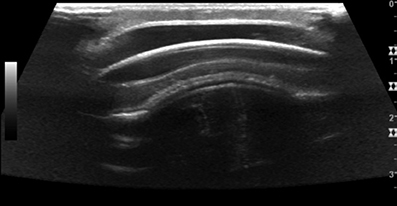

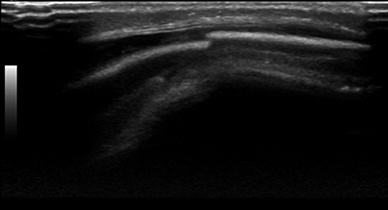

A grayscale ultrasound scan of the region of the concern in the right parietal region revealed a hypoechoic fluid collection with a focal step-off at the outer table of the skull, just beyond the posterior-lateral aspect of the fluid collection (Figures 1 and 2). This was highly concerning for a skull fracture with associated cephalohematoma.

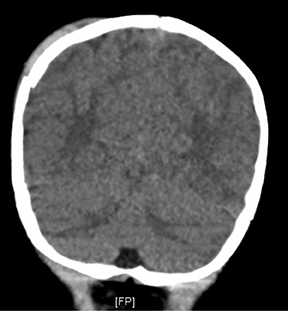

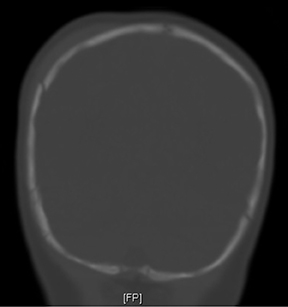

A non-contrast axial CT of the head with coronal reconstructions was performed immediately after the ultrasound. This confirmed the suspected right parietal skull fracture and cephalohematoma. In addition, it also demonstrated a small right epidural hematoma (Figures 3, 4 and 5). MR imaging should be considered to evaluate for blood in various stages of evolution in the setting of a pediatric skull fracture (to assess for non-accidental trauma).

DIAGNOSIS

Pediatric skull fracture without mechanism

DISCUSSION

Diagnostic imaging studies available for evaluation of suspected skull fracture include non-contrast CT, ultrasound, and plain film radiography. Non-contrast CT has a sensitivity and specificity for detecting skull fractures of 71% and 95%, respectively.1 Non-contrast CT has become very common for evaluating skull fracture due to its widespread availability and advantage of visualizing acute intracranial pathology. The downside to this modality is the radiation dose. Also, in some instances, sedation may be needed to obtain diagnostic-quality images in the pediatric population. Plain radiographs expose children to much less radiation than CT; however, the sensitivity and specificity for plain radiographs in detecting skull fractures are 63% and 87%, respectively1 (less than CT). Due to its inferior sensitivity and specificity, and its inability to visualize intracranial pathology, plain radiography is not nearly as commonly performed as non-contrast CT in cases of suspected skull fracture.

In contrast to both previous modalities, ultrasound does not use ionizing radiation. An advantage specific to the pediatric population is that ultrasound may be performed without sedation.2 The sensitivity and specificity for identifying fractures are 88% to 100%, and 95% to 97%, respectively.2,3 The only reported instance of a false-negative ultrasound on a child with a skull fracture was when the skull was imaged directly under the scalp hematoma, but the fracture was located adjacent to the borders of the hematoma.2 The disadvantages of ultrasound are that it is operator-and patient-dependent, and cannot adequately visualize potentially acute intracranial abnormalities.

Three main differentials for pediatric head swelling are caput succedaneums, subgaleal hemorrhage, and cephalohematomas. A caput succedaneum is a collection of blood under the skin and above the cranial aponeurosis, which occurs most commonly during birth. It crosses suture lines, usually causes no complications, and resolves within a few days after birth.4 A subgaleal hemorrhage is located under the cranial aponeurosis and above the periosteum. This location allows a subgaleal hemorrhage to cross suture lines. This occurs when emissary veins between the scalp and dural sinuses are sheared as a result of traction on the scalp most often associated with vacuum assisted delivery, prematurity, coagulopathies, or prolonged labor.4,5,6 This is a dangerous condition for infants, as they present with significant blood loss, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and increased intracranial pressure.5,6

A cephalohematoma is blood collection under the periosteum of a given cranial bone and, due to this anatomic location, is confined by the cranial sutures.4 Cephalohematomas can be caused by prolonged labor or instrumentation during delivery – especially vacuum assisted, fracture, or other various conditions causing trauma to vessels of the periosteum.4 Complications can include jaundice secondary to increased RBC destruction or infection leading to meningitis or osteomyelitis.4

CONCLUSION

Trauma and skull fracture should be on the differential for any new onset pediatric head swelling. Ultrasound may be used to evaluate this finding, and a careful evaluation of the skull should be made to look for any skull fractures.

REFERENCES

- Mulroy MH,Loyd MA, Frush DP, et al. Evaluation of pediatric skull fracture imaging technique. Forensic Science International. 2012;214:167-172.

- Rabiner JE, Friedman LM, Khine H, et al. Accuracy of point-of-care ultrasound for diagnosis of skull fractures in children. Pediatrics. 2013;131;e1757. Originally published online May 20, 2013. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/131/6/e1757.full.html

- Parri N, Crosby BJ, Glass C, et al. Ability of emergency ultrasonography to detect pediatric skull fractures: a prospective, observational study. J Emer Med. 2013;44:135-141.

- Slovis, TL. Caffey’s Pediatric Diagnostic Imaging. Mosby Elsevier. 2008;1:502-504.

- Plauché WC. Subgaleal hematoma. A complication of instrumental delivery. JAMA. 1980;244:1597.

- Amar, AP, Aryan HE, Meltzer, HS, et al. Neonatal subgaleal hematoma causing brain compression: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:14701474.

Citation

Pediatric Skull Fracture Without Mechanism. Appl Radiol.

June 5, 2014