Polyarteritis nodosa in a pediatric patient

Images

CASE SUMMARY

A 13-year-old Hispanic female with no significant past medical history presented to an outside facility with episodic vomiting, abdominal pain, 20-lb unintentional weight loss, and malaise over a four-week span. Visits to the urgent care and emergency room during this time period resulted in diagnoses of gastroesophageal reflux and gastritis with unsuccessful treatment regimens. Just prior to her presenting admission, she developed a fever and worsening abdominal pain followed by a grand mal seizure at home and additional four episodes at the outside hospital. Her severely elevated blood pressure (reaching upwards of 190/110 mmHg) was difficult to control, leading to her subsequent transfer to a higher level of care at our institution.

IMAGING FINDINGS

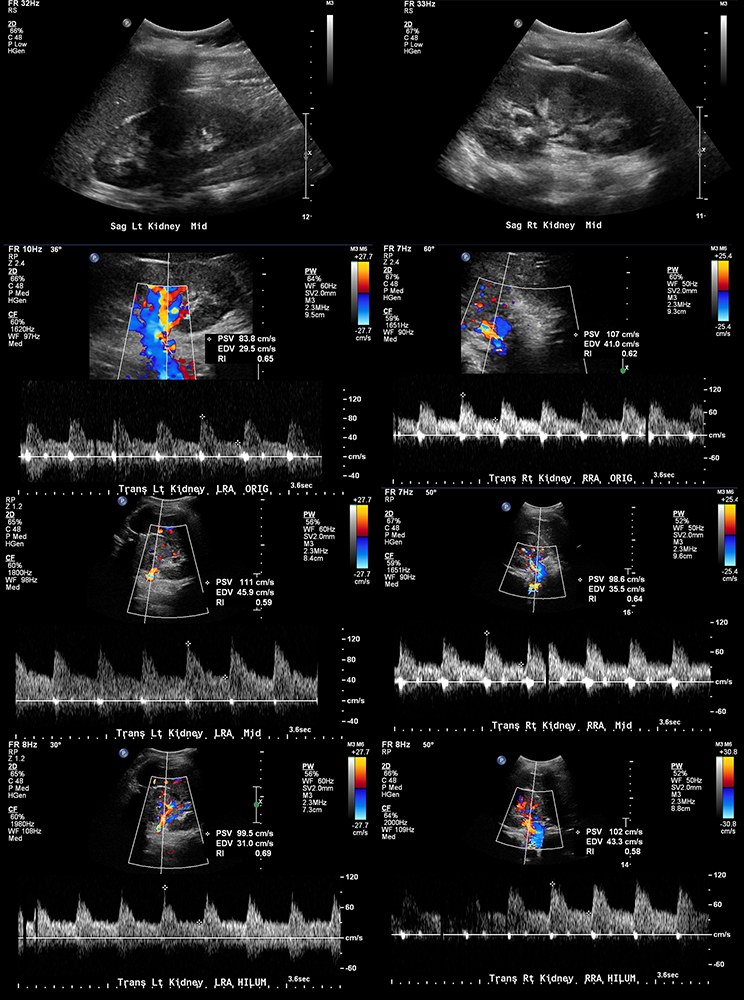

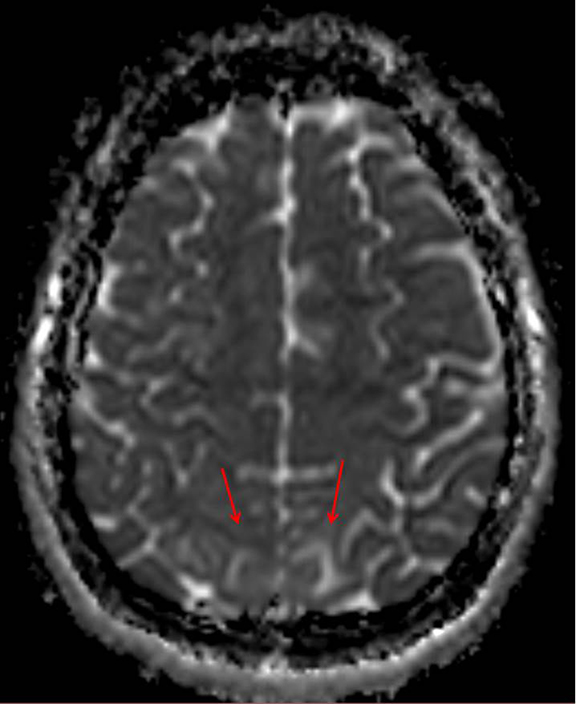

Initial imaging workup of her malignant hypertension and seizures included a duplex renal ultrasound and MRI of the brain. Renal duplex ultrasound (Figure 1) was normal. Initial MRI demonstrated multifocal cortical/subcortical ischemic changes, which raised the concern for vasculitis versus an atypical appearance of acute hypertensive encephalopathy (Figure 2). Additional laboratory findings were significant for hematuria, proteinuria and elevated creatinine. Nephrology and rheumatology were subsequently consulted. Pertinent lab values included an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. She was negative for hepatitis B antibody/surface antigens, antiglomerular basement membrane antibody, antinuclear antibodies and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA). C3/C4 levels were normal.

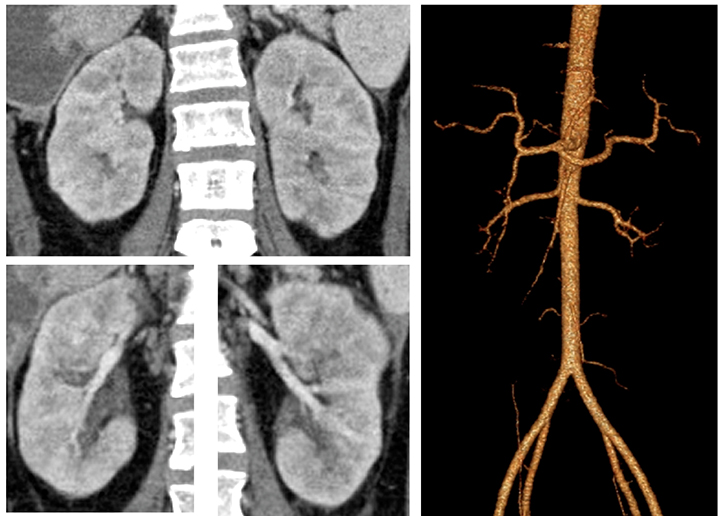

Abdominal CT angiography was performed (Figure 3) and demonstrated normal parenchymal and branch pattern of the renal arteries into the hilum. Three-dimensional reconstructed images demonstrated normal renal arteries to the second order.

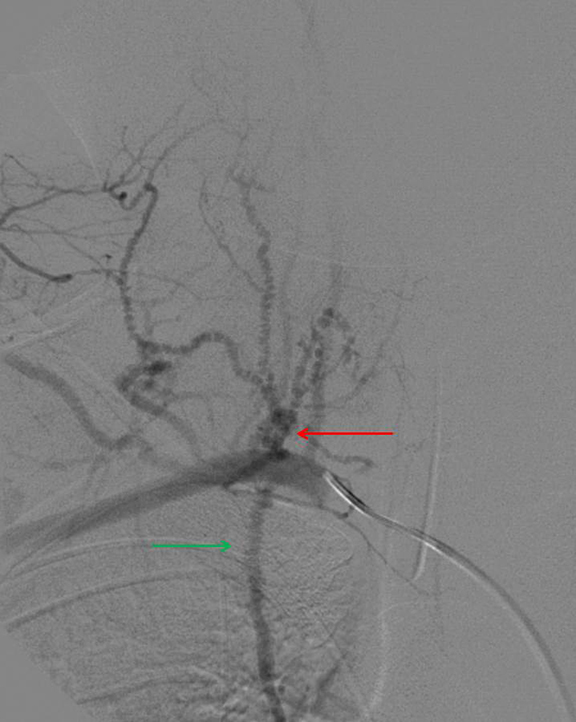

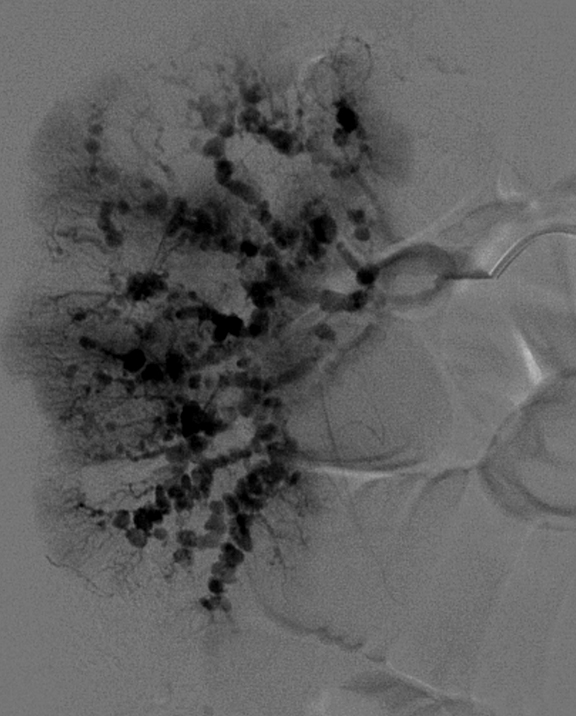

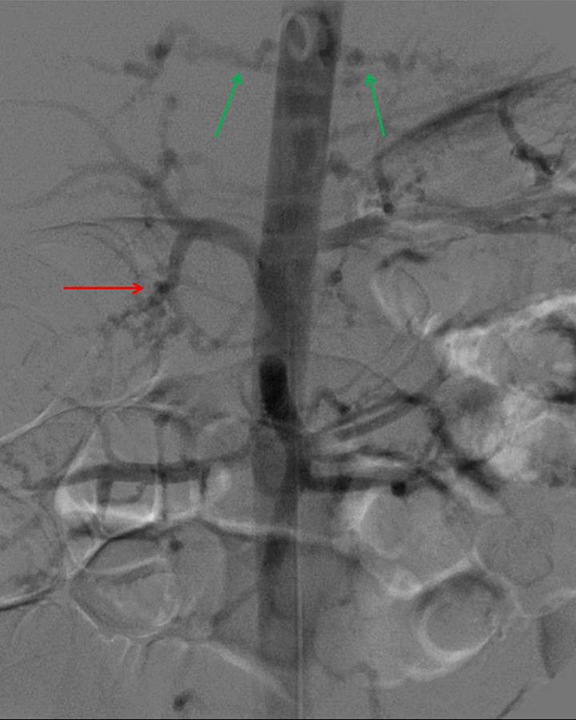

Given the imaging, clinical and biochemical findings, polyarteritis nodosa became the working diagnosis, prompting angiography. Cerebral angiogram demonstrated no abnormal intracranial vascularity or aneurysm. When evaluating the right vertebral artery, the right thyrocervical trunk and distal branches, as well as the right internal mammary, demonstrated a beaded appearance (Figure 4). Subsequent renal angiogram (Figures 5-7) demonstrated innumerable sub-centimeter second order branch intrarenal aneurysms. Additionally, there was beaded appearance of the gastroduodenal artery and bilateral inferior intercostal arteries (Figure 7). These angiographic findings further supported the working diagnosis of polyarteritis nodosa.

The patient was treated with steroids, cyclophosphamide and antihypertensives. Her hospital stay was complicated by bowel resection secondary to ischemic vasculitis in addition to widespread fungal and bacterial disease secondary to immunosuppression. After a prolonged hospital course, she was ultimately discharged to an inpatient rehabilitation facility.

DIAGNOSIS

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN).

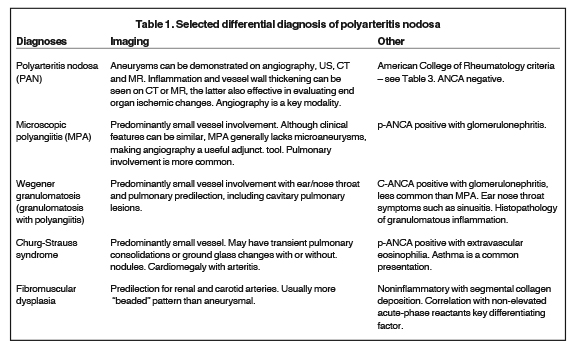

Differential diagnosis includes microscopic polyangiitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Wegener granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss and fibromuscular dysplasia. PAN can share similar imaging findings with these other entities (Table 1), requiring multidisciplinary correlation of disease for accurate diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

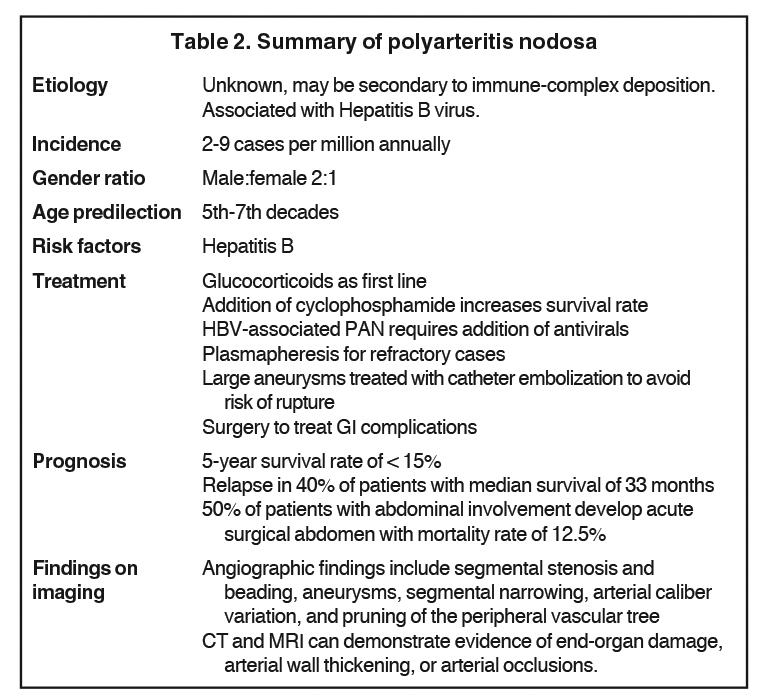

Polyarteritis nodosa, also known as Kussmaul-Maier disease, is a rare entity in the pediatric population.1,2 As it is superseded only by Henoch Schonlein purpura and Kawasaki disease, it remains an important differential when vasculitis is suspected.2 Although thought to possibly stem from infectious triggers of host response, the etiology is still unknown.3 Disease onset most commonly occurs in the fifth to seventh decades with a male predilection. Increasing case reports suggest the disease in the pediatric population may occur more frequently than the literature suggests.2 PAN is a disease of predominantly medium-sized vessels, but can also involve small vessels. Organ involvement includes kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, peripheral nervous system, skin, skeletal muscles, heart, liver, spleen and pancreas.2,4,5 Clinical symptoms are usually secondary to organ ischemia from arterial branch occlusions.5 The disease is summarized in Table 2.

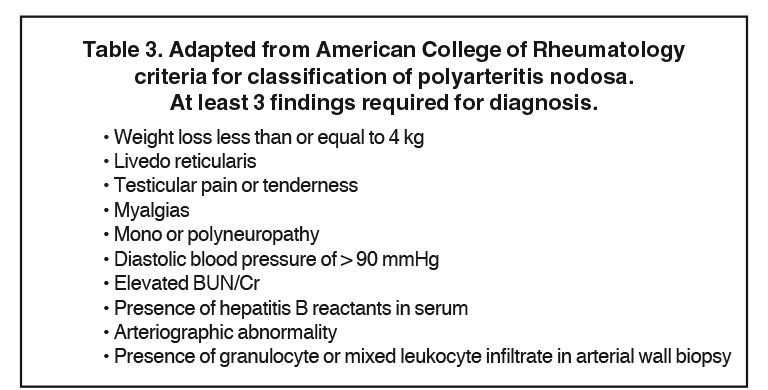

According to the American College of Rheumatology (Table 3), criteria for polyarteritis nodosa includes any three of the following 10 criteria: weight loss greater than or equal to 4 kilograms, livedo reticularis (mottled reticular pattern over the skin, extremities or torso), testicular pain or tenderness (not due to infection, trauma or other causes), myalgias, mononeuropathy or polyneuropathy, diastolic blood pressure greater than 90 mmHg, elevated blood urea nitrogen or serum creatinine levels (not due to dehydration or obstruction), presence of hepatitis B surface antigen or antibody in serum, arteriographic abnormality (aneurysms or occlusions of the visceral arteries not due to arteriosclerosis, fibromuscular dysplasia or other noninflammatory causes), and presence of granulocyte or mixed leukocyte infiltrate in an arterial wall biopsy.6 In our patient, four of these criteria were met.

Definitive diagnosis is made by tissue biopsy of a symptomatic organ. Characteristic pathologic findings are fibrinoid necrotizing inflammatory foci in the walls of small or medium-sized arteries with multiple small aneurysms.4 The role of angiography is to confirm or support the clinical suspicion of PAN when there are no suitable biopsy sites available or when biopsy results are inconclusive. If PAN is strongly suspected, histological confirmation is not mandatory for diagnosis. Patients with the disease will show segmental stenosis and beading, aneurysms, segmental narrowing, arterial caliber variation, and pruning of the peripheral vascular tree.7,8 Although CT and MRI remain suboptimal as compared to conventional angiography, both modalities can demonstrate evidence of end-organ damage, arterial wall thickening, arterial aneurysmal dilatation or arterial occlusions.7 Renal cortical scintigraphy with technetium 99m dimercapto-succinic acid (DMSA) can demonstrate areas of photopenia relating to ischemia.3

Polyarteritis nodosa is usually fatal if left untreated with a 5-year survival rate of less than 15 percent.5 Development of an acute abdomen is associated with a 50 percent mortality rate.1 Prompt treatment with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide improves 5- year survival to 80 percent,5 making early recognition paramount. Additional treatments include plasma exchange and plasmapheresis, which can provide added benefit in refractory cases. Large aneurysms may be treated with catheter embolization to avoid risk of rupture.7

CONCLUSION

Polyarteritis nodosa is a rare entity in the pediatric population that should be considered in patients of any age with symptoms related to vasculitis. It shares similar angiographic findings with other vasculitides necessitating multidisciplinary correlation for accurate diagnosis. Early diagnosis can lead to significant improvement in survival rates. If PAN is strongly suspected, histological confirmation may be substituted by positive angiographic findings. CT and MRI can demonstrate evidence of end-organ damage and vascular pathology.

REFERENCES

- Beckum, K.M., et al. Polyarteritis nodosa in childhood: Recognition of early dermatologic signs may prevent morbidity. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31(1): e6-9.

- Eleftheriou, D., et al. Systemic polyarteritis nodosa in the young: A single-center experience over thirty-two years. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(9):2476-2485.

- Eleftheriou, D. and P.A. Brogan. Vasculitis in children. Paediatrics and Child Health. 2014;24(2):58-63.

- Siegert, C.E., et al. Systemic fibromuscular dysplasia masquerading as polyarteritis nodosa. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11(7):1356-1358.

- Stanson, A.W., et al. Polyarteritis nodosa: Spectrum of angiographic findings. Radiographics. 2001;21(1):151-159.

- Bloch, D.A., et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of vasculitis. Patients and methods. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(8):1068-1073.

- Ozaki, K., et al. Renal involvement of polyarteritis nodosa: CT and MR findings. Abdom Imaging. 2009;34(2):265-270.

- Rhodes, E.S., et al. Case 129: Polyarteritis nodosa. Radiology. 2008;246(1):322-326.