Pediatric renal cell carcinoma

Images

CASE SUMMARY

An otherwise healthy 5-year-old male presented to the Emergency Department with a right-side abdominal mass. The mass was discovered by his parents when he experienced abdominal pain after roughhousing.

IMAGING FINDINGS

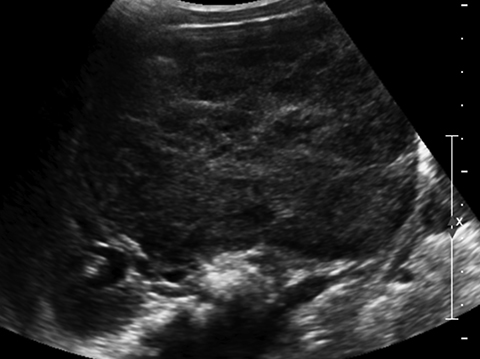

An abdominal ultrasound demonstrated the presence of a solid, 10.8 × 7.4 × 8.1 cm mass arising from the lower pole of the right kidney (Figure 1). Color flow imaging demonstrated flow within the lesion. Additionally, the right renal vein and IVC were patent.

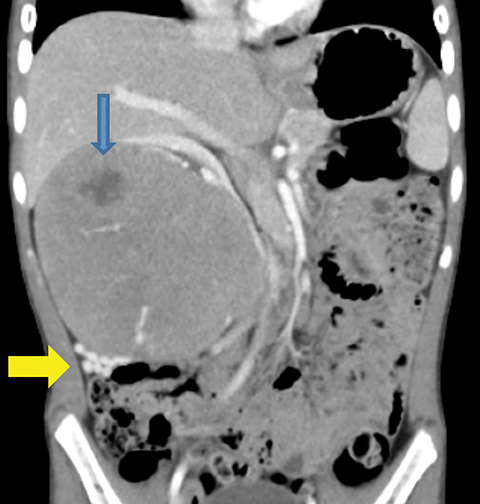

Helical CT images of the chest, abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast confirmed the presence of an 8 × 11 × 9.4 cm heterogeneously enhancing mass arising from the mid pole of the right kidney. This mass contained areas of low attenuation consistent with hemorrhage, tissue necrosis and cystic degeneration on pathologic examination. There were no additional ipsilateral or contralateral renallesions, intra-lesional calcifications, nor was there thrombus in the right renal vein or IVC. Additionally, there were numerous enhancing collateral veins inferolateral to the mass, which were continuous with prominent veins in the lesion (Figures 2a-2c). Other than masseffect on the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas, all of the adjacent organs were normal.

DIAGNOSIS

Renal cell carcinoma

DISCUSSION

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is very uncommon in children, accounting for an approximate 2 to 5% of all pediatric renal malignancies.1 Wilms’ tumor is the most common renal malignancy in the pediatric population. Renal cell carcinoma, a prevalent renal tumorin adults, originates within the epithelium of renal tubules and includes a subset of tumors described most often by papillary, clear cell,chromophobe and oncocytoma morphology.2 Wilms’ tumor accounts for over 90% of renal tumors in children and up to 7% of all pediatric malignancies.1 The overall survival for pediatric RCC is 72%, which is greater than the reported 63% for all non-Wilms’ renal tumors (NWRT’s) [renal cell carcinoma, clear cell sarcoma, and malignant rhabdoid tumor] as seen in a large scale study by Zhuge, et al, culminating in 2010.1

A significant number of pediatric patients with RCC have underlying genetic disorders such as von Hippel-Lindau disease, or haveundergone therapy for prior malignancies, such as Wilms’ tumor or neuroblatsoma.3 These cases suggest that RCC is often a secondmalignancy in children who have survived previous diseases, possibly from radiation or chemotherapy.3 Many pediatric RCCs occurin patients in the second decade of life, which also supports a causal relationship to underlying medical conditions that present early inlife.1 When compared to other NWRTs, renal cell carcinoma has one of the highest survival rates in children.1 As expected, the pediatricNWRT study by Zhuge, et al supports that prognosis improves when there is no distant metastatic disease and when the tumor remainswell or moderately differentiated.1 Surgical resection is the primary treatment modality for pediatric RCC as no studies currently support an increase in survival after the use of adjuvant or neo-adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy.1,4

Many patients with pediatric RCC are symptomatic at diagnosis, experiencing combinations of hematuria, abdominal pain, and/or an abdominal mass.4,2 Most pediatric RCCs present as a large, solitary mass, although the size is known to vary greatly and bilateral, multifocal, and metachronous tumors have also been observed.3 The use of imaging is very important in the initial assessment of pediatricRCC and has been supported by the Children’s Oncology Group (COG).3 An ultrasound will detect the presence of a renal lesion butCT or MR imaging can help to determine the TNM staging. Contrast-enhanced CT imaging of RCC is utilized to assess tumor size,local extension of the mass, enhancement pattern, presence or absence of calcification, lymph node enlargement, vascular invasion,neo-vascularity, presence of an ipsilateral or contralateral lesion, and for identification of metastatic disease.3 Calcifications within the mass may be indicative of RCC.1 The CT findings will guide the surgical intervention, specifically whether there will be a nephron sparing partial nephrectomy or total nephrectomy. While necessary for initial characterization of the renal mass, imaging alone istypically insufficient for distinguishing renal cell carcinoma from Wilms’ tumor. Wilms’ tumor should be the primary considerationin the differential diagnosis of a renal mass due to its high prevalence in children. Fortunately, when immediate, aggressive treatmentis required, both types of renal malignancies are best treated by surgical resection as a first step.

Incidences of RCC in children and adults are diagnosed differently due to variations in morphologic and genetic characterizationof the disease.2 Papillary renal cell carcinoma is the most common subtype of pediatric RCC.2 Pathology evaluation will subsequentlyprovide the diagnosis.5 Additionally, the relationship between an RCC’s morphologic subtype and its genetic characteristics may provehelpful.2 Papillary RCC, as considered in the case of our patient, is most commonly associated with an Xp11.2 translocation.6 Therefore,thorough pathologic assessment of the tumor is vital for proper diagnosis.

CONCLUSION

Renal cell carcinoma is a rare malignancy in the pediatric population. Studies of RCC in children have been limited in scope given the disease occurs infrequently in patients under 20 years of age. Radiologic imaging is invaluable for characterizing and staging RCCs, aswell as for guiding surgical management. The first route of treatment after diagnosis is typically partial or complete nephrectomy giventhat chemotherapy and radiation therapy do not increase survival.

REFERENCES

- Zhuge Y, Cheung MC, Yang R, et al. Pediatric non-Wilms’ renal tumors: Subtypes, survival, and prognostic indicators. J Surg Res. 2010;163:257-263.

- Morabito RA, Talug C, Zaslau S, et al. Asymptomatic advanced pediatric papillary renal cell carcinoma presenting as a pulmonary embolus. Urology. 2010;76(1):153-155.

- Downey RT, Dillman JR, Ladino-Torres MF, et al. CT and MRI appearances and Radiologic Staging of Pediatric Renal Cell Carcinoma. Pediatr Radiol. 2012;42:410-417.

- Sausville JE, Hernandez DJ, Argani P, et al. Pediatric renal cell carcinoma. J Pediatr Urol. 2009;5:308-314.

- Schultz TD, Sergi C, Grundy P, et al. Papillary renal cell carcinoma: Report of a rare entity in childhood with review of the clinical management. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46(6):e31-e34.

- Chen L, Deng F, Melemed J, et al. Differential diagnosis of renal tumors with tubulopapillary architecture in children and young adults: A case report and review of literature. Am J Clin Exp Urol. 2014;2(3):266-272.