Parapagus dicephalus dibrachius dipus conjoined twin case

Images

CASE SUMMARY

A 37-year-old G4P2A2 Hispanic female presents for her initial obstetrical visit at a gestational age of 12 weeks and four days. She has a history of one therapeutic abortion and one spontaneous abortion (third pregnancy). The patient is blood type O-positive, has an equivocal rubella titer and tests positive for tuberculosis (QuantiFERON).

IMAGING FINDINGS

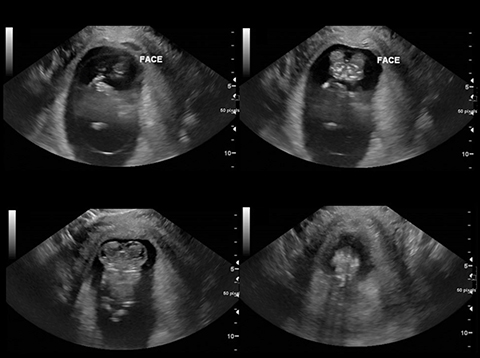

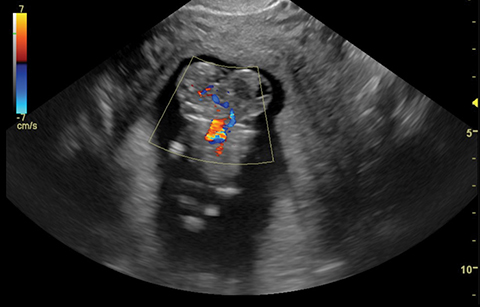

Grayscale transvaginal ultrasound demonstrates a fetus with duplicated maxillofacial and calvarial structures fused at midline (Figure 1). There is a solitary heart with shared intracranial vasculature, two upper and two lower extremities (Figure 2).

DIAGNOSIS

Conjoined twin pregnancy of the parapagus dicephalus dibrachius dipus (PDDD) type. This type of conjoined twin is defined by lateral fusion with two heads, sharing a single thorax, abdomen and pelvis with two arms and two legs.

DISCUSSION

Conjoined twins occur in approximately 1 percent of monoamniotic monochorionic monozygotic twins.1 The reported global prevalence ranges from 1:50,000 to 1:100,000 births.1,2 Of the small number of conjoined twins born alive, there is a 30 percent mortality rate within the first 24 hours of life.1 Overall, there is a 2:1 female predominance of conjoined twins.

Historically, there have been two opposing embryologic theories for the development of conjoined twins: “fission” and “fusion.” The former attributes the development of conjoined twins to incomplete division of the developing embryo, while the latter argues that all eight types occur by secondary fusion of two embryonic discs beyond the 13th day post-conception.3

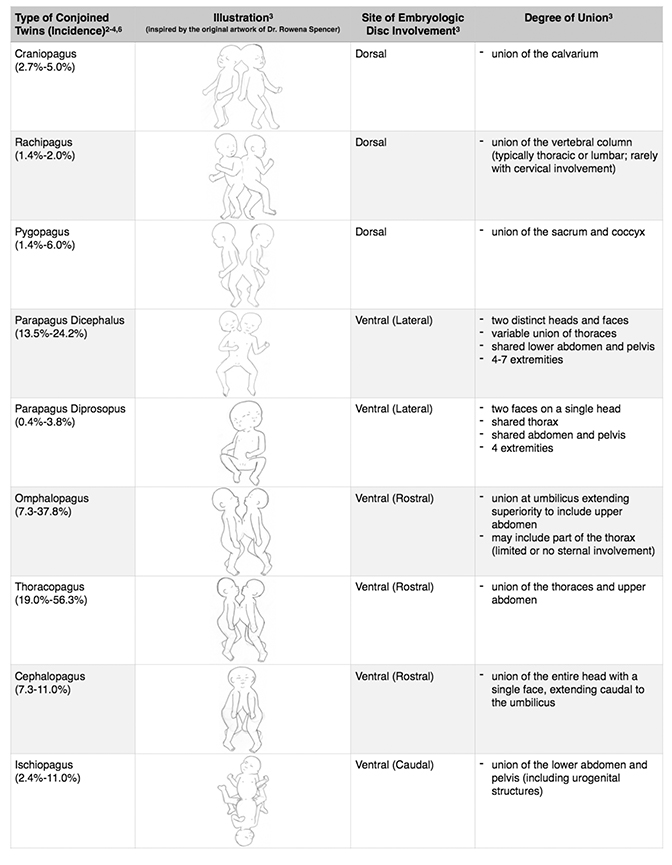

Conjoined twins are divided into two main groups, ventral and dorsal, based on the location of embryonic disc union. They are further classified into eight basic types relative to their site(s) of union or pagus (Greek for joined): Omphalopagus (umbilicus/abdomen), thoracopagus (thorax/upper abdomen), cephalopagus (maxillofacial), craniopagus (skull), ischiopagus (pelvis), rachipagus (spine) and pygopagus (sacrum). Additional terminology includes the suffixes: -parapagus (fused laterally/side-by-side), -brachius (upper limb), -pus (lower limb) and -prosopus (face).3

Parapagus conjoined twins can be divided into two types: Parapagus dicephalus (two heads, single trunk/abdomen/pelvis with 4-7 limbs) which was the presented case, and parapagus diprosopus (two faces on a single head, single trunk/abdomen/pelvis and four limbs). The classification of conjoined twins is summarized in Table 1 and the various subtypes of parapagus dicephalus are summarized in Table 2.3

The distance between the rostral ends of the embryonic disc increases as the spectrum of parapagus conjoined twins progresses from diprosopus to dicephalus. As this distance increases, there is increasing separation of the conjoined twins; the heads separate first, followed by the thoraces, while the number of limbs increases from four to a maximum of seven.3

Conjoined twins often have several associated anomalies in various organ systems, including musculoskeletal, cardiac, gastrointestinal, and the central nervous system. As the number of limbs and degree of separation increases, so does the likelihood of organ duplication. For example, parapagus diprosopus twins (parapagus type with the least degree of physical separation) will share a single heart. However, parapagus dicephalus twins have greater separation that may result in a partially duplicated or two separate hearts. This phenomenon is not limited to the thorax and the same principles apply to the abdomen, pelvis, and CNS.3

The earliest published diagnosis of conjoined twins via sonography was seven weeks’ gestation (thoracopagus type).4 A conjoined twin can be ruled out if there is visualization of two placentae or a membrane separating the twins. The following sonographic diagnostic criteria for conjoined twins have been proposed: “absent separating membrane, conjoined body parts, inseparable bodies or heads between the twins despite changes in fetal position or a bifid appearance of the fetal pole in the first trimester.”5

Other findings suggestive of conjoined twins include: An umbilical cord with greater than three vessels, persistence of fetal position and anatomy relative to one another on repeat scans. Identification of shared organs is critical in guiding management as the main clinical dilemma is determining if the twins can be surgically separated.

Multiple case reports encourage the use of three-dimensional sonography to diagnose conjoined twins.1,6 Three-dimensional sonography improves specificity regarding the level of fusion and degree of shared anatomy. Three- dimensional sonography also aids in parent counseling as it helps demonstrate disease severity and illustrate reason for prognosis.

CONCLUSION

The early diagnosis of a conjoined twin pregnancy is important in guiding clinical management. Classification of conjoined twins is a relatively simple system based on sites of fetal union. Establishing a correct diagnosis and identifying shared organs will help determine the possibility for fetal separation and minimize morbidity.

The authors thank Nicole Miravite for illlustrating Tables 1 and 2.

REFERENCES

- Bega G, Wapner R, Lev-Toaff A, Kuhlman K. Diagnosis of conjoined twins at 10 weeks using three-dimensional ultrasound: a case report. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Sep;16(4):388-390.

- Mutchinick OM, Luna-Muñoz L, Amar E, et al. Conjoined twins: a worldwide collaborative epidemiological study of the International Clearinghouse for Birth Defects Surveillance and Research. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2011 Nov 15;157C(4):274-287.

- Spencer R. Theoretical and analytical embryology of conjoined twins: part II: adjustments to union. Clin Anat. 2000;13(2):97-120.

- Chen CP, Hsu CY, Su JW, Cindy Chen HE, Hwa-Ruey Hsieh A, Hwa-Jiun Hsieh A, Wang W. Conjoined twins detected in the first trimester: A review. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Dec; 50(4):424-431.

- Tongsong T, Chanprapaph P, Pongsatha S. First-trimester diagnosis of conjoined twins: a report of three cases. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Dec;14(6):434-437.

- Yang PY, Wu CH, Yeh GP, Hsieh CT. Prenatal diagnosis of parapagus diprosopus dibrachius dipus twins with spina bifida in the first trimester using two- and three-dimensional ultrasound. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Dec;54(6):780-783.

Citation

CDA B, JR Y, M C.Parapagus dicephalus dibrachius dipus conjoined twin case. Appl Radiol. 2018; (5):29-32.

May 8, 2018