NUT Carcinoma

Images

Case Summary

An adult presented with a rapidly growing, painless bump over the left forehead, gradual loss of vision in the left eye, and poor medial peripheral vision. Physical examination revealed a large mass on the left forehead involving the left supraorbital region, extending into the eye. There was no ulceration, breach of overlying skin, or significant pain on palpation.

Imaging Findings

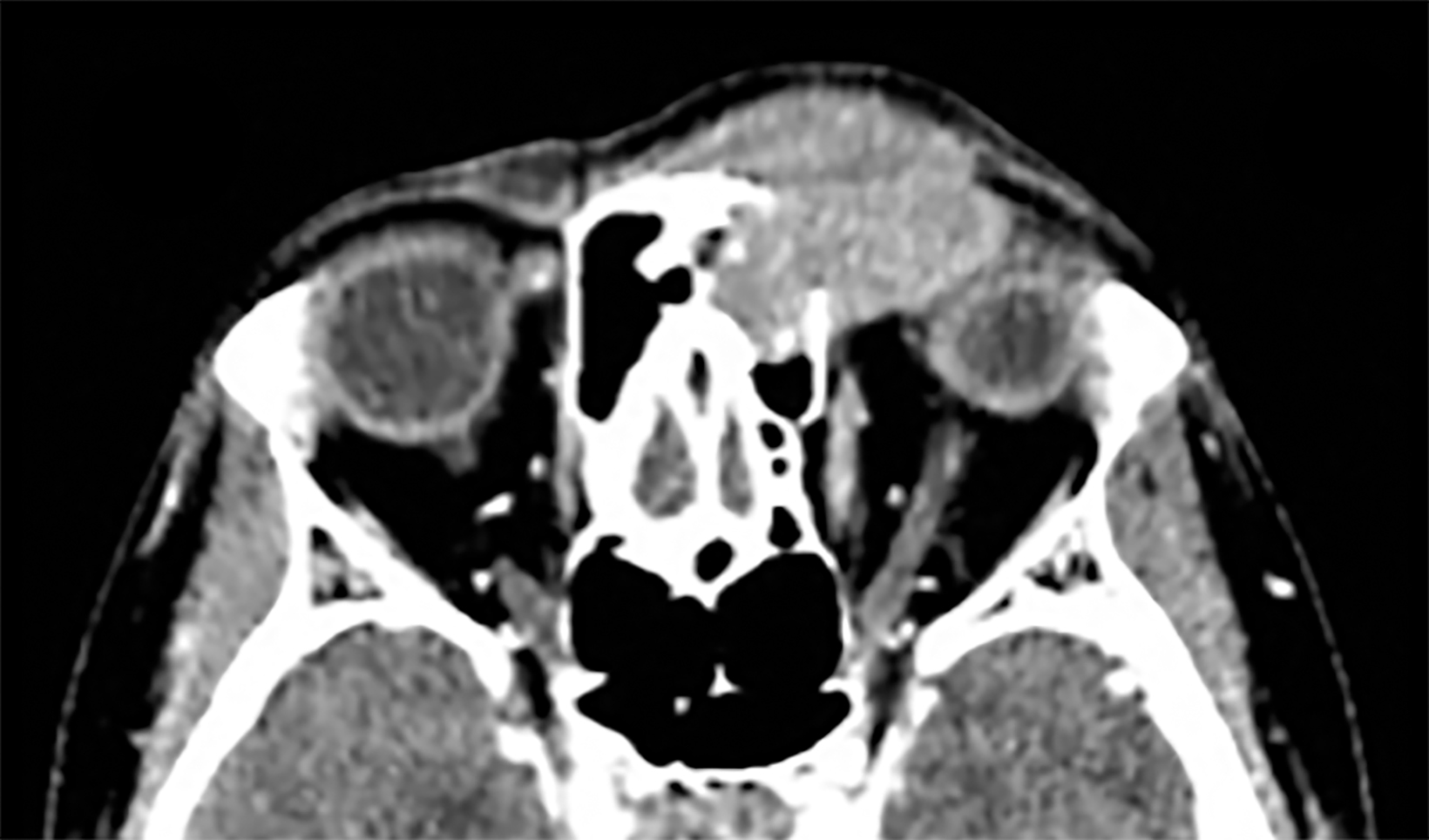

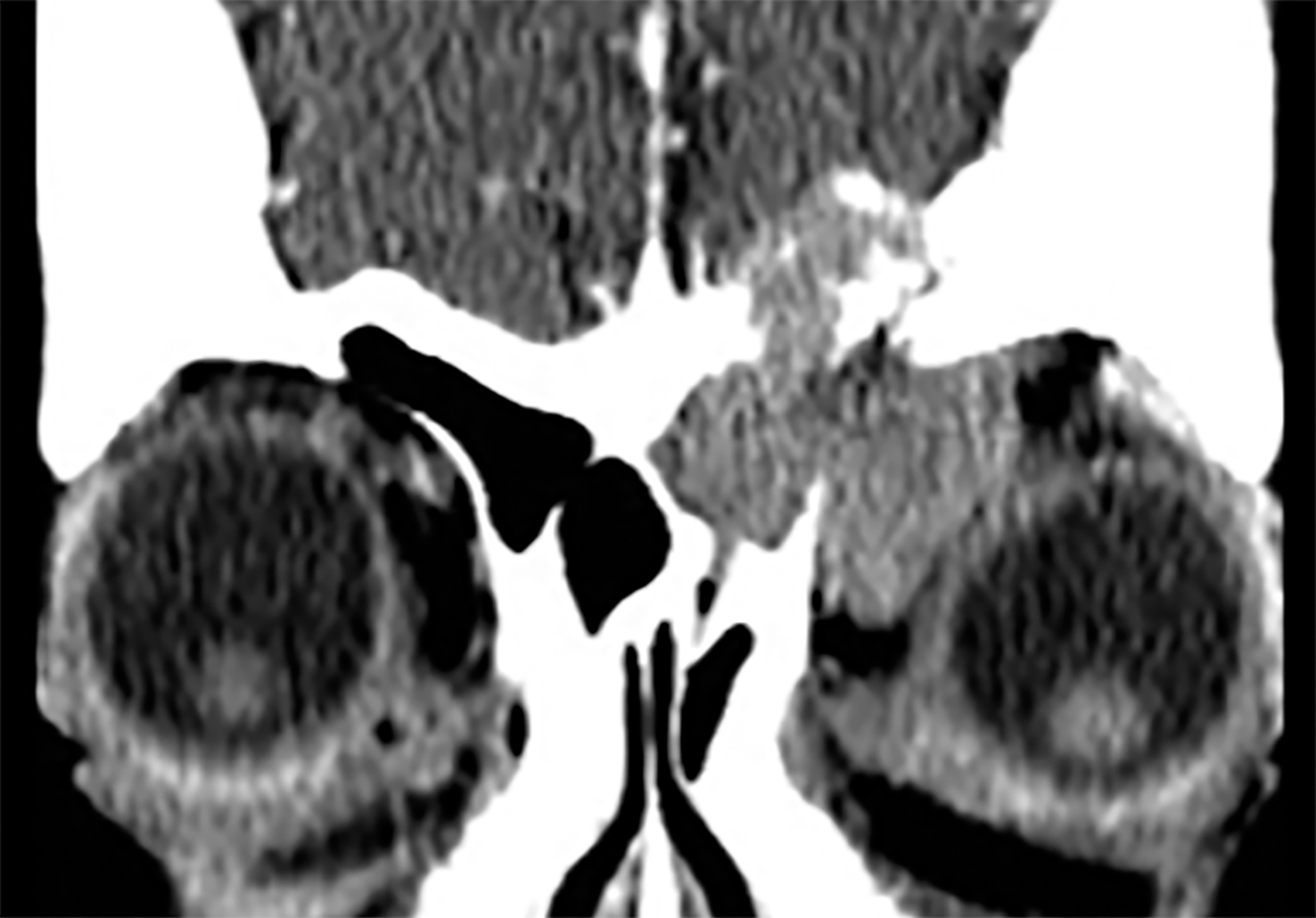

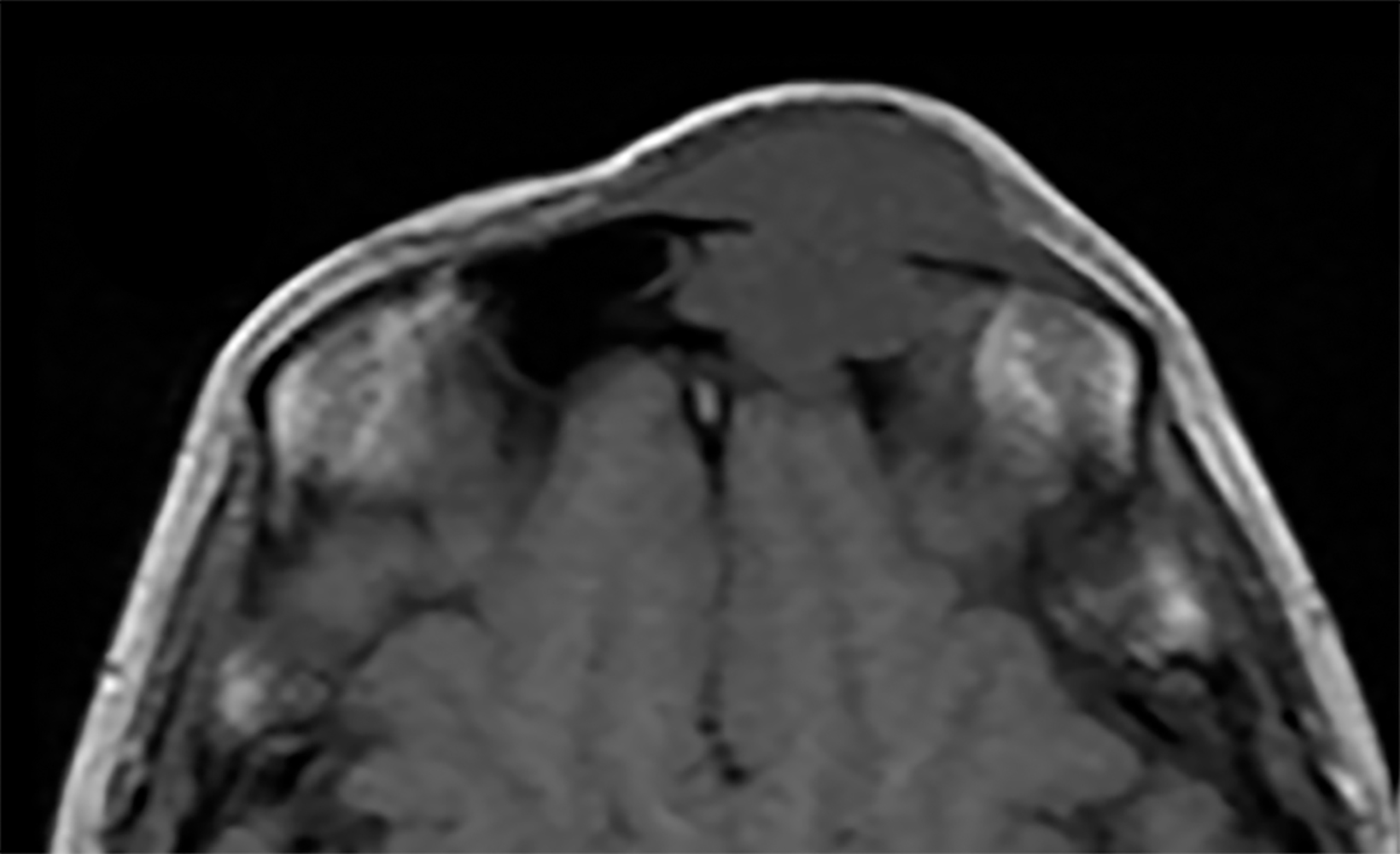

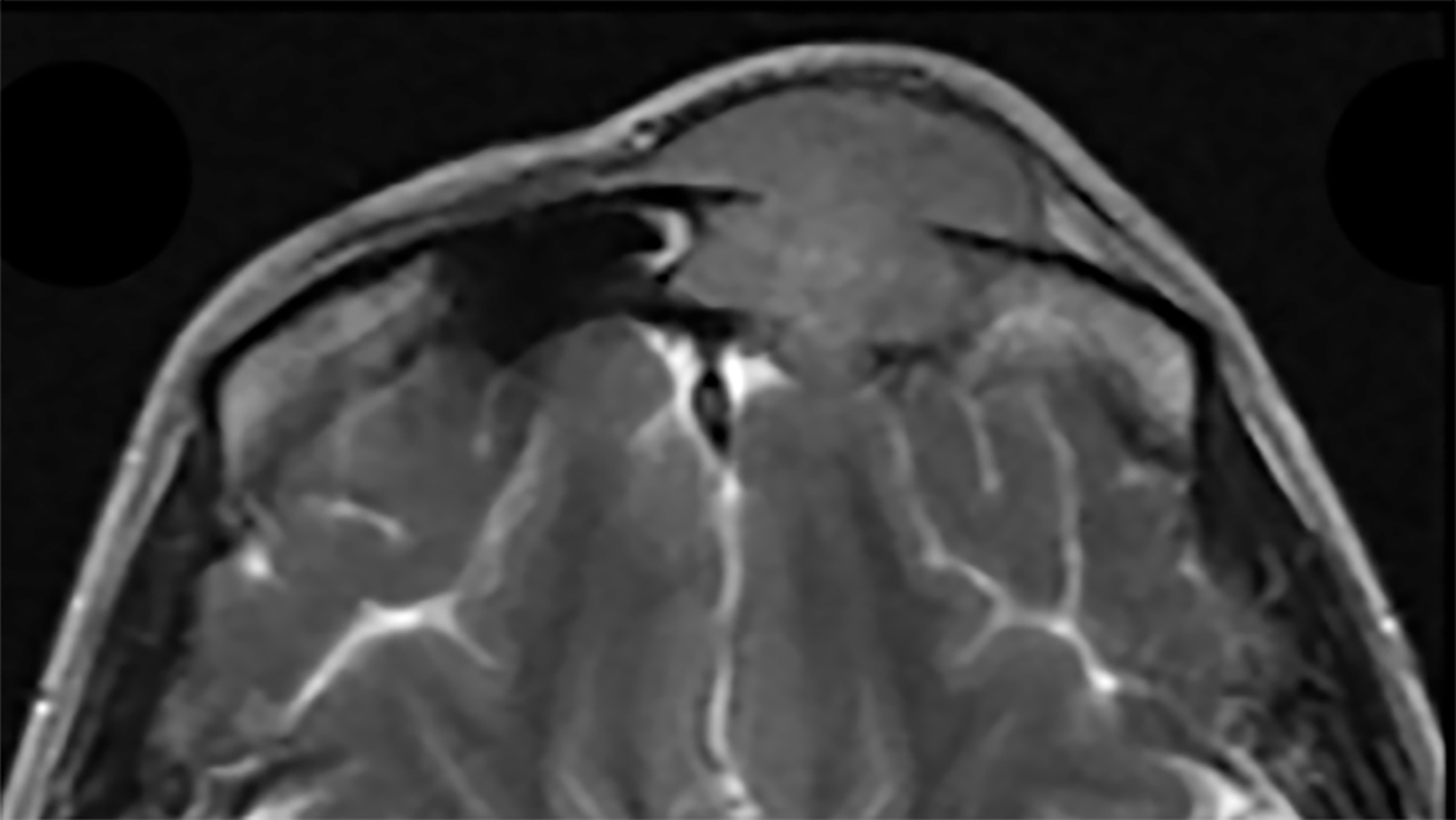

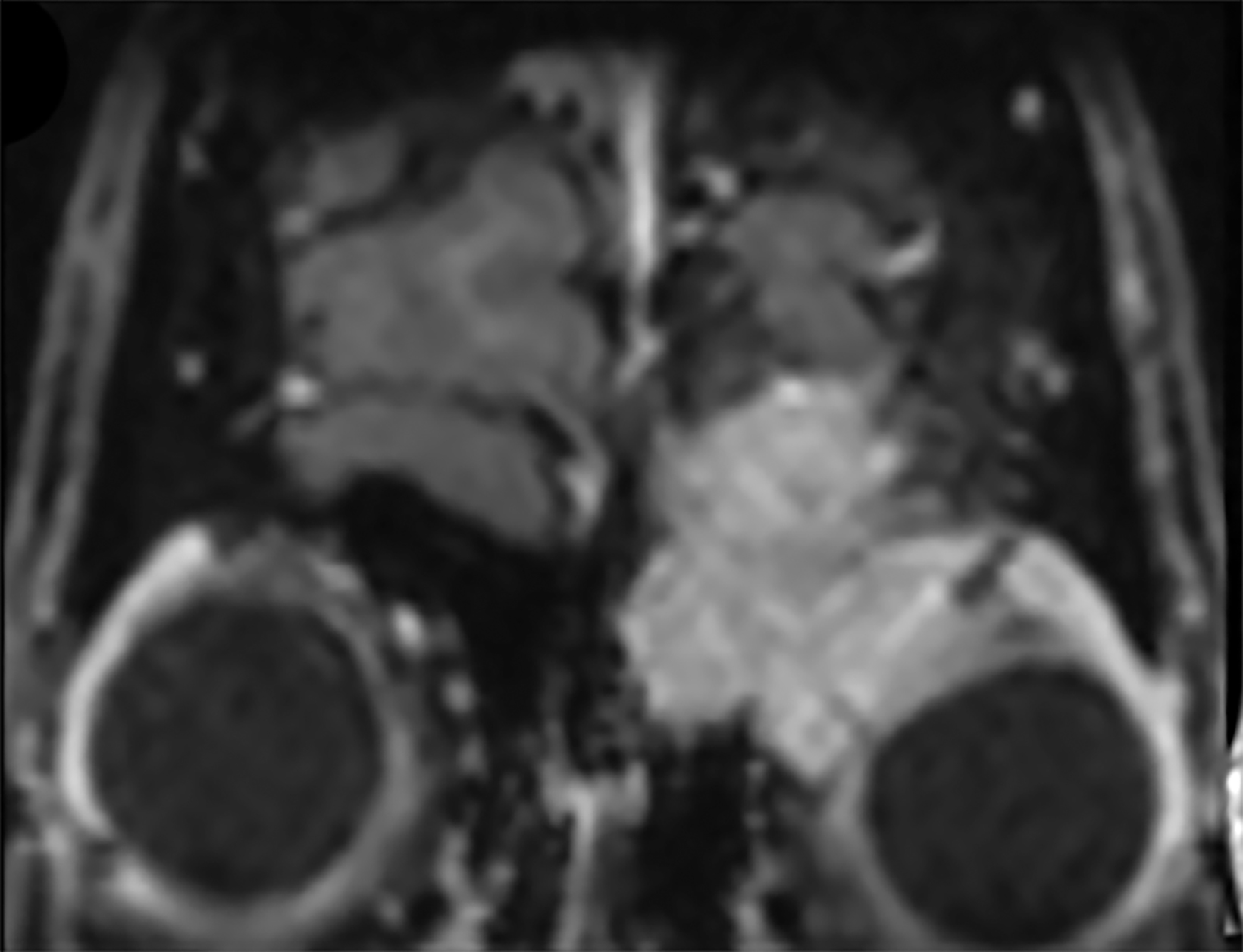

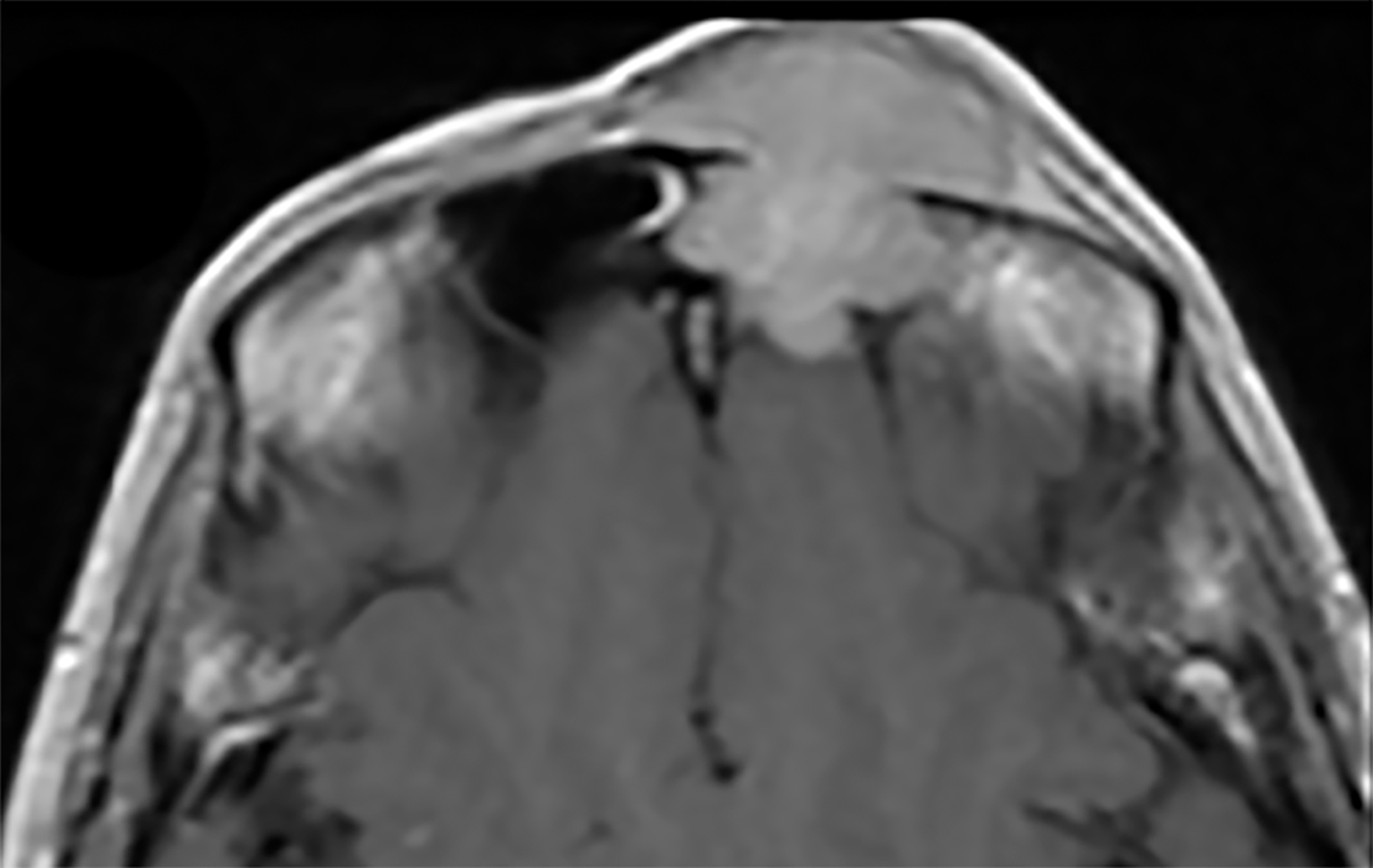

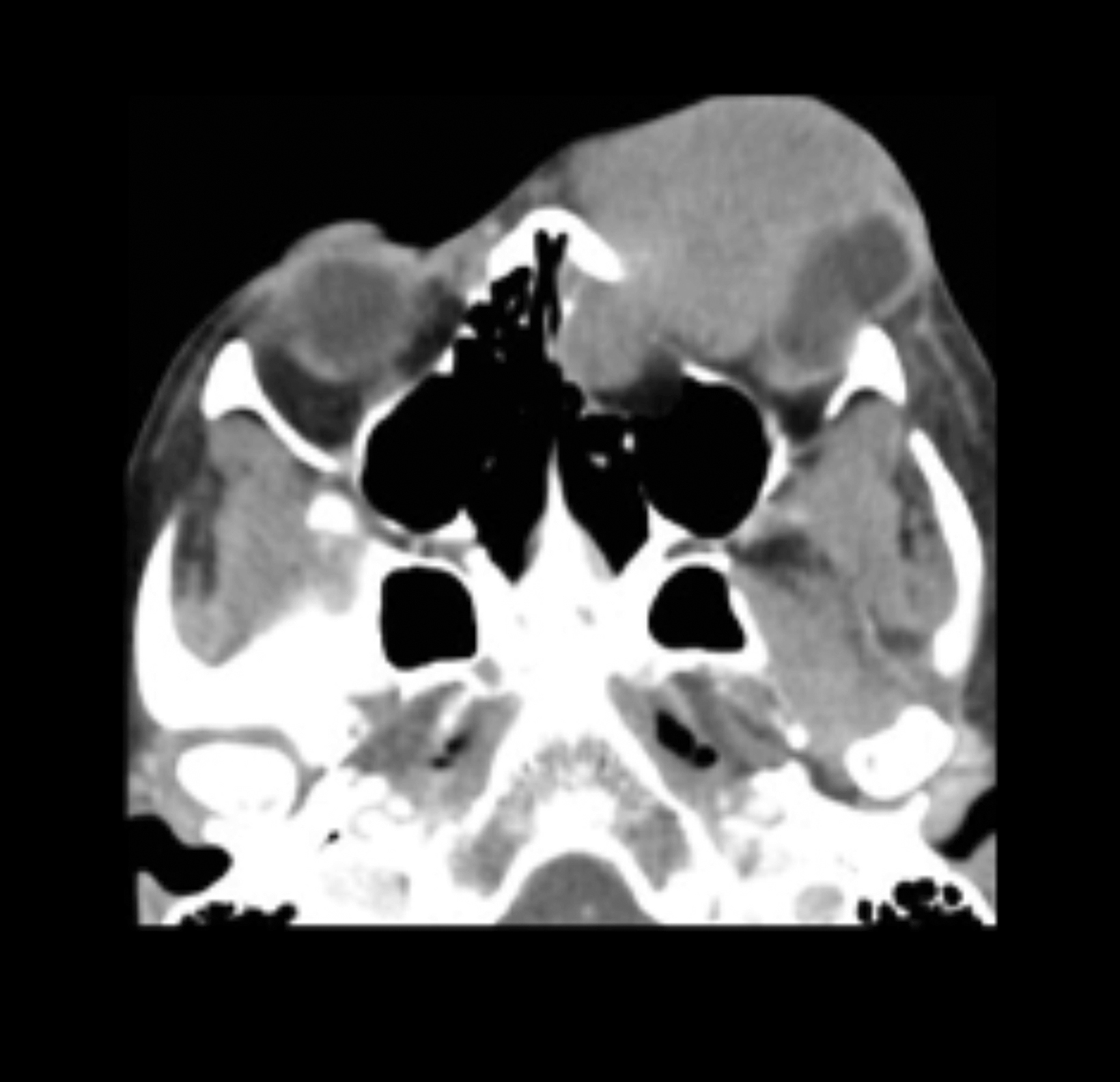

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (Figure 1) and magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 2) revealed an aggressive, enhancing, soft-tissue mass centered in the left ethmoid sinus. There was a significant interval increase in tumor size with increased mass effect and tumoral extension into the anterior cranial fossa on short-term follow-up imaging (Figure 3).

Excisional biopsy of the left frontal mass was performed. Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) staining demonstrated poorly differentiated cells, focal necrosis, and abrupt keratinizing of squamous cells while high-molecular-weight staining was positive for keratin and p63. Additional immunohistochemical and fluorescence in situ hybridization testing were positive for NUT midline carcinoma. Radical chemoradiotherapy resulted in tumor shrinkage; the patient subsequently underwent radical craniofacial resection with flap reconstruction. Unfortunately, the patient developed cerebral abscesses and calvarial metastasis and passed away less than 9 months following initial presentation.

Diagnosis

NUT carcinoma. Differential diagnosis includes squamous cell carcinoma, and Ewing sarcoma, lymphoma, and sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma (SNUC).

Discussion

NUT carcinoma (NC) is characterized by chromosomal rearrangements that involve the gene encoding the NUT protein. Genetically, NC is defined by chromosomal rearrangements involving the NUT gene on chromosome 15q14. In 70% of cases, the NUT gene is fused to bromodomain extra-terminal (BET) gene BRD4 on chromosome 19p13.1, forming a BRD4-NUT fusion oncogene. 1,2,3,5,9

In the remaining cases, NUT is fused to the closely related BRD3 gene and other partner genes (NUT variant). NUT carcinoma was initially described in children and adolescents, but there is an increasing frequency of diagnosis in adults. 8,10 The median age at diagnosis is 16 years (range, 0.1–78 years), with no predilection for either sex. 1,6,8,10 Actual NC incidence is unclear, and it is almost certainly underdiagnosed owing to the need for a specific (100%) and sensitive (87%) immunohistochemistry test for nuclear NUT expression. In fact, up to 18% of undifferentiated carcinomas of the head and neck are NC. Definitive diagnosis is not possible based solely on imaging, owing to the lack of pathognomonic imaging findings. However, a midline head and neck tumor with an infiltrative, aggressive appearance and rapid progression warrant including NC in the differential diagnosis. 10

No established and effective treatment regimen exists for NC; various treatment paradigms include combinations of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Chemo/radiotherapy alone is often inadequate. Aggressive initial surgical resection with clear margins, with or without postoperative chemo radiation, is associated with significantly increased survival. 4, 6,7 Targeted therapy with BET protein bromodomain inhibitors (acetyl histone mimics) targeting BRD4-NUT are currently being used in clinical trials. 7

Conclusion

NUT carcinoma should be considered in any poorly differentiated sinonasal carcinoma with aggressive imaging features and p63 positivity.

References

- French CA. NUT carcinoma: Clinicopathologic features, pathogenesis, and treatment. Pathol Int. 2018; 68(11):583-595.

- Edgar M, Caruso AM, Kim E, Foss RD. NUT midline carcinoma of the nasal cavity. Head and Neck Pathol. 2017;11(3):389-392. doi: 10.1007/s12105-016-0763-0

- French CA. NUT midline carcinoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010; 203(1):16–20.

- Chau NG, Hurwitz S, Mitchell CM, et.al. Treatment and survival outcomes in NUT midline carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 2016;122(23): 3632-3640.

- Bishop JA, French CA, Ali SZ. Cytopathologic features of NUT midline carcinoma: A series of 26 specimens from 13 patients. Cancer Cytopathology. 2016;124(12):901-908. DOI: 10.1002/cncy.21761

- Bauer DE, Mitchell CM, Strait KM, et.al. Clinicopathologic features and long-term outcomes of NUT midline carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(20):5773-5779.

- Napolitano M, Venturelli M, Molinaro E, et.al. NUT midline carcinoma of the head and neck: current perspectives. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:3235-3244.

- Lemelle L, Pierron G, Fréneaux P, et.al. NUT carcinoma in children and adults: A multicenter retrospective study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017; 64(12).

- Albrecht T, Harms A, Roessler S, et.al. NUT carcinoma in a nutshell: A diagnosis to be considered more frequently. Pathol Res Pract. 2019; 215(6):152347.

- Liu S, Ferzli G. NUT carcinoma: a rare and devastating neoplasm. BMJ Case Rep. 2018 Sep 1;2018: bcr2018226526. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-226526.

References

Citation

JKR N, M J, M H, R S, H L, C F, J L.NUT Carcinoma. Appl Radiol. 2021; (6):54-55.

November 6, 2021