Neurocysticercosis

Images

Summary

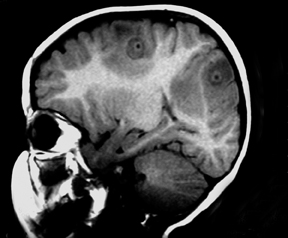

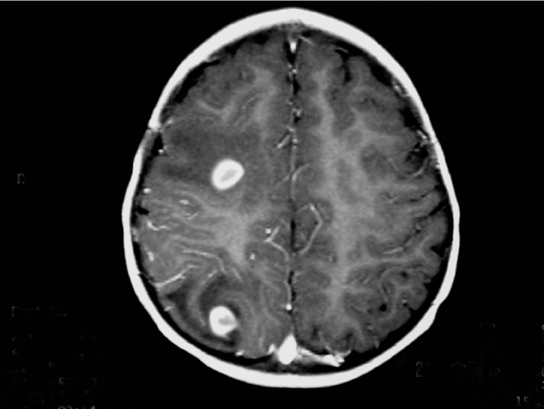

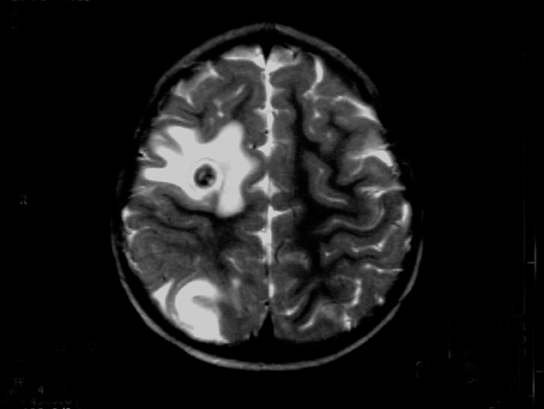

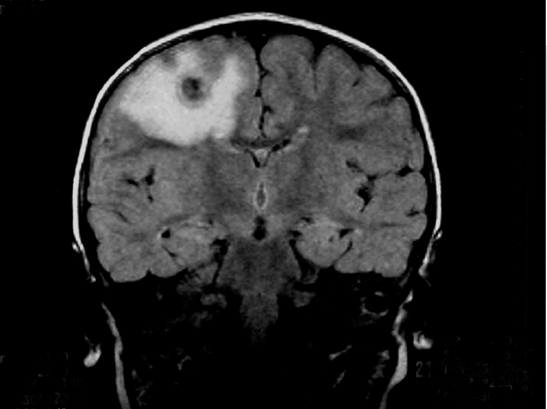

An 18-month-old child born to a Mexican immigrant mother resident in Texas presented with a convulsive crisis in the emergency room.1 Her pregnancy and his birth history were unremarkable. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination of the child’s brain was performed (Figure 1).

Imaging Findings

The images show several round, ring-enhancing lesions at the gray matter-white matter interface measuring approximately 1 cm in diameter. Each is associated with vasogenic edema, but there is no midline shift or subfalcine or transtentorial herniation.

Diagnosis

Neurocysticercosis

Differential diagnoses: Pyogenic abscesses, tuberculomas, metastases, tuberous sclerosis, and toxoplasmosis.

Discussion

Neurocysticercosis results when encysted larval forms of Taenia solium (pork tapeworm) invade the central nervous system.2 It is the most common parasitic disorder of the CNS,5 occurring in 4% of autopsy series from endemic countries of the world (in Latin America, Asia, Africa, and some European countries).

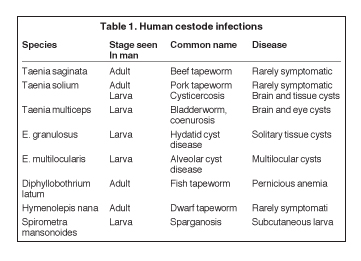

Taenia solium is one of the 8 cestode species that infect man (Table 1). Humans are the definitive host for the parasite (harboring the adult worm), while omnivorous or herbivorous vertebrates (like pigs) host its larval form (intermediate host). Although the adult forms of the cestodes that humans host rarely cause harm, the larval forms cause variable degrees of illnesses in humans. In the former case the parasites often reside harmlessly in the bowels, while in the latter they invade the tissues.

For example, in the pork tapeworm’s normal life cycle, humans harbor the parasite and shed its eggs (either individually or in proglot tides impregnated with eggs) in our feces. The pig, an omnivore and its natural intermediate host, consumes the eggs of the parasite, which hatch into larval forms in its alimentary tract and invade its tissues. Consumption of undercooked meat from infected pork by humans completes the cycle, freeing the encysted larvae when they encounter gastric acid and bile salts.

In contrast, humans act as the intermediate host of the parasite when they ingest the tapeworm eggs by eating food infected with them (the mother in this case may have infected her child this way). Their larvae invade the bowel walls and invade human tissues as far afield as the brain, eyes, muscles, heart, and others, wreaking havoc along the way.4

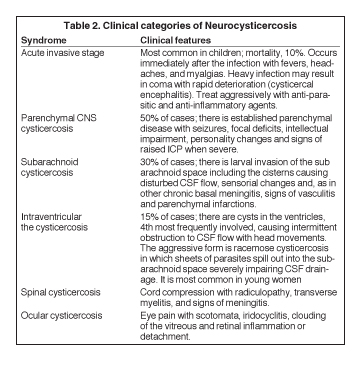

In the CNS, the cysticerci (the larvae) may lodge in the brain parenchyma, the spinal cord, the subarachnoid space, or the ventricles, lying dormant for years or causing various categories of clinical disease (Table 2).5 However, 2 to 10 years after CNS invasion, the dormant cysts may die, lose osmoregulation, absorb fluid and disintegrate, releasing antigens that set up variable degrees of inflammation. The clinical conundrum that results from CNS larval invasion depends upon the size of the invasion, and the location and degree of the inflammation.

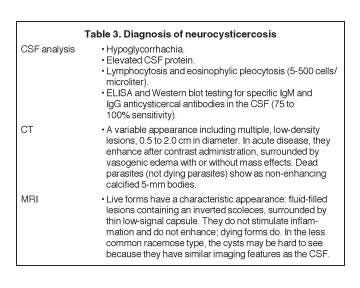

A certain diagnosis of neurocysticercosis can be made by analyzing infected tissue microscopically. But a presumptive diagnosis of the disease can be made if the patient is from or resides in an endemic area (as in this case) and, if laboratory analysis of their CSF specimen, including an immunoblot test, and their CNS imaging results are positive for markers of the disease (Table 3).5,6

For cysts that cause symptoms outside the CNS, surgical resection achieves a cure.

The treatment of symptomatic neurocysticercosis, which carries 50% mortality rate, is more problematic. Two drugs, albendazole and praziquantel, control symptoms and cause regression in the size and number of cysts in patients with viable (nonenhancing) cysts in the brain parenchyma. However, they provide limited improvement in patients with arachnoiditis and no improvement in patients with intraventricular cysts. These latter patients should be treated with surgery or palliated with ventricular shunting, anticonvulsants, and anti-inflammatory drugs. According to our case’s physician, the patient did not receive antiparasitic medication because the imaging features suggested that the parasites were dying (vasogenic edema and ring enhancement).7

Two cautionary injunctions about treatment: First, 20% of patients with parenchymal cysticercosis worsen symptomatically following institution of drug treatment as the parasites die and release their antigens. Concomitant administration of antiinflammatory drugs subdues this phenomenon. Second, because anti-inflammatory agents alter the CNS pharmakokinetics of the anti-parasitic agents, their routine use is discouraged.

Patients should be rescanned 3 months after therapy to judge their response to treatment; an alternative drug to the one used ab initio can be used if there is no response.

For patients with ocular cysticercosis (remember, 20%), it is preferable to hold off drug treatment until resection of their lesions because they do not respond well to medication.

Conclusion

MRI is an effective examination for evaluating neurocysticercosis and other similar conditions. Utilizing techniques, such as axial T1W image after IV gadolinium administration, axial T2W image, and coronal FLAIR images, effectively depicts enhanced views of the lesions at the gray matter-white matter interface.

References

- Shandera WX, White AC Jr, Chen JC, et al. Neurocysticercosis in Houston, Texas. A report of 112 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1994;73:37-52.

- Domenici R, Matteucci L, Meossi C, Stefani G, Frugoli G. Neurocysticercosis: A rare cause of convulsive crises. Pediatr Med Chir. 1995;17(6):577-581. [in Italian]

- Caparros-Lefebvre D, Lannuzel A, Alexis C, et al. Cerebral cysticercosis: Why it should be treated. Presse Med. 1997;26:1574-1577. [in French]

- Ruiz-Garcia M, González-Astiazaran A, Rueda-Franco F. Neurocysticercosis in children. Clinical experience in 122 patients. Childs Nerv Syst. 1997;13:608-612.

- Grill J, Pillet P, Rakotomalala W, et al. Neurocysticercosis: Pediatric aspects. Arch Pediatr. 1996;3(4):360-368. [in French]

- Riley T, White AC Jr. Management of neurocysticercosis. CNS Drugs. 2003;17):577-591.

- Rahalkar MD, Shetty DD, Kelkar AB, et al. The many faces of cysticercosis. Clin Radiol. 2000;55:668-674.

Citation

Neurocysticercosis. Appl Radiol.

January 18, 2013