Hanging bladder stone

Images

Prepared by W. Forrest Carson, MD, Robert Bechtold, MD, and Ray Dyer, MD from the Department of Radiology; and Joel C. Hutcheson, MD from the Department of Urology, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC.

CASE SUMMARY

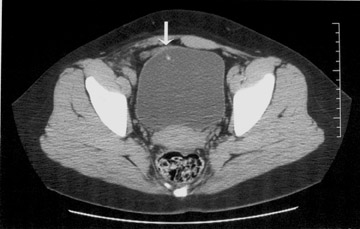

A 17-year-old girl presented to her nephrologist with complaints of nausea, vomiting, and dysuria. Her medical history was significant for renal failure secondary to nephritis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Two years prior to her presentation, she had received a renal transplant from a living-related donor. She also reported a history of recurrent urinary tract infections while on prophylactic therapy. Despite having just completed a 10-day course of antibiotics, her urine culture was positive for Escherichia coli and Klebsiella . A urologic consultant recommended a computed tomography (CT) examination to exclude anatomic causes for the recurrent urinary tract infections (Figure 1).

DIAGNOSIS

Hanging bladder stone

IMAGING FINDINGS

An unenhanced CT image through the pelvis, above the bladder, shows mild hydronephrosis in the right iliac fossa transplant kidney (Figure 1A). The ureteroneocystostomy can be identified entering the right anterior aspect of the bladder (Figure 1B). An image obtained at a slightly lower level reveals a stone hanging from the anterior bladder wall near the ureterovesical junction (Figure 1C). At cystoscopy, the stone was dangling from the anterior wall of the bladder, attached by nonabsorbable suture. Removal of the stone necessitated division of the suture (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

Bladder calculi are divided into migrant, primary endemic, and secondary types. 1 Migrant calculi are the most common, forming in the kidney and migrating down the ureter into the bladder. Once in the bladder, they are usually mobile and, if imaged before they pass, they will fall to a dependent position. 2 They can remain in the bladder in cases of bladder outlet obstruction, where they may enlarge. Primary endemic calculi usually occur in children and young adults and are related to the diet in underdeveloped countries. 1 Secondary bladder calculi are often seen in adults as a consequence of urinary stasis. In men, this is most commonly the result of prostatic enlargement with outflow obstruction. In women, stones may develop as a result of cystocele formation. A neurogenic bladder with associated urinary stasis may be a cause in both sexes. 1

An uncommon, but well-recognized, cause of secondary bladder calculi is formation on a foreign body. The foreign body may serve as a nidus for crystallization with resultant stone formation. Bladder stones appearing to defy gravity and hanging from the anterior bladder wall were first described by Levack in 1955. 3 As in this case, the stones in the original report formed on nonabsorbable suture material. Stone formation has also been reported on bladder catheter balloons, 1 mesh used for treatment of incontinence, 4 surgical staples, 5 and other nonabsorbable material chronically exposed to urine. 6

CONCLUSION

The diagnosis of a hanging stone may be difficult by standard radiographic examinations. The CT finding of a curious, nondependent stone location should prompt review of the patient's history for a surgical procedure involving nonabsorbable material. In this case, the anastamosis of the transplant ureter with the bladder was created using a nonabsorbable, running prolene suture that served as the nidus for stone formation. In the modern era of CT examination, this old stone, "just hanging around," is revealed in a new way.