Avoiding pitfalls in adding to a PACS or changing PACS vendors

Images

Dr. Horii is a Professor of Radiology and the Clinical Director of Medical Informatics, the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA.

Increasingly, radiology practices are deciding to add to an existing picture archiving and communications system (PACS) or to change PACS vendors entirely. These are among the most challenging transitions a radiology practice will ever face. This article will discuss why it maybe desirable to upgrade a PACS, how to manage the project, and some pitfalls to watch out for.

Adding to a PACS

The decision to add to a PACS is often driven by imaging subspecialties. Existing PACS often fail to meet the needs of radiologists who interpret ultrasound or nuclear medicine studies, for example. An ultrasound system must be able to handle not just color imaging but multiple cine loops, Doppler wave forms, and other complex tasks that PACS supplied by the major vendors often don't handle. Nuclear medicine studies involve similar challenges, particularly in the mathematical analysis of images. Cardiology is also placing new demands on PACS, as cardiologists have different requirements from radiologists when interpreting images. At the same time, new capabilities for advanced visualization may drive the need to add to or change a PACS.

Upgrading is difficult because the PACS interacts with so many other systems and devices. There are a tremendous number of interfaces involved, and that complexity affects information flow. Network loads may change, for example, and a larger amount of storage may be needed. Studies may begin to incorporate new images, as advanced imaging techniques enable radiologists to create 3-dimensional (3D) series from data that was already part of the image acquisition.

Similarly, new imaging equipment raises new issues. If cardiology is being integrated into the PACS, images should flow to the archive directly from the angiography systems. To do that, it is necessary to interface with equipment in the catheterization laboratory. Table 1 summarizes some tips for adding to a PACS.

Avoiding pitfalls

PACS and radiology information systems (RIS) do not exist as stand-alone systems. They interface with a number of other systems, including hospital information systems, pharmacy systems, admission-discharge-transfer systems, billing systems, and others. Software and hardware changes have the potential to affect the way those interfaces operate.

It is critical to consider how information will move among several PACS. Should we go back to the old store-and-forward days of routing images to where they're needed? How do we do that with different kinds of PACS? How do we get the information where it's needed, when it’s needed?

At a minimum, interfaces usually require the setting of parameters by both vendors involved. The software on both sides of the interface is expecting certain behavior and data across that interface, and is sensitive to very small changes.

When managing interface changes, keep in mind that vendors generally accept responsibility only for their hardware and software and for managing their side of any interface. They will not be responsible for what is on the other side of the interface, unless an agreement to that effect has been negotiated or the same vendor manufactures both pieces of equipment.

The process of installing a new system, new software release, or new hardware usually results in downtime. Management of this process is important because it affects all users. Be aware that a system that worked perfectly during testing can still develop problems during installation. It is unlikely that any vendor can exactly reproduce your system configuration for testing.

There are many stories of major problems that developed after the addition of a new system or a change in software on an existing system. Usually, the systems themselves work, but the interface fails. For example, when we installed a new CT scanner at the University of Pennsylvania, the PACS stopped acquiring images. Both devices were DICOM conformant, but the network interface had been set for a particular scanner. When we changed that scanner, we had to change the parameters on the network interface to suit the performance of the new machine.

To avoid such problems, it is essential to completely understand the projected work flow and movement of information across the interfaces between systems, especially between a new PACS and the existing one. There must be a strict policy in place covering any changes and upgrades. Vendors should understand the policy and sign off on it. Such an agreement can avoid the common problem of a vendor who performs preventive maintenance on a scanner and, without the explicit consent of the radiologist, also installs some new software. Often it is only when the scanner stops sending images to the PACS that the radiologist becomes aware of the software upgrade.

Consider having a test system that enables the testing of changes before they are actually implemented in operational systems. As mentioned earlier, this will not catch all of the little, irritating problems that might occur, but it will catch the big ones that prevent the system from operating.

Understand that knowledge is power. A radiologist who is knowledgeable about the interfaces between systems, what those interfaces do, and what information flows across them is in a much better position to determine whether a new system is likely to impact an existing system.

It is also important to understand that interfaces have both upstream and downstream dependencies. A change on one side may affect the way devices operate on the other side.

Changing to a new PACS

If adding to an existing PACS is challenging, changing to a new PACS vendor is daunting. Many radiology departments are doing just that, however. There are several reasons why. A vendor may go out of business or be purchased by another company, for example. In addition, an existing PACS may no longer support the department’s current work, or it may not expand to meet new needs. If the PACS cannot handle the advanced visualization needed for cardiac imaging, a new PACS may be needed.

A corporate decision may drive the change to a new PACS. If the hospital is purchased by a larger entity, hospital administration may sign an exclusive purchase agreement with a particular vendor. One radiology practice may take over an existing one with a very large installed base. A new radiology chairman may have a preferred system and initiate the change in the PACS vendor.

The University of Pennsylvania has changed PACS vendors 3 times. The first time, the vendor for our ultrasound mini-PACS left the business. Our main PACS vendor could not handle ultrasound images in the way we needed, so we had to make a change to a new ultrasound mini-PACS. In another case, our health system established an exclusive relationship with a single imaging equipment vendor, and we were required to change vendors for our departmental PACS. We eventually changed back when the new system could not meet our needs.

Challenges

There is no question that changing to a new PACS is painful. The most intense pain does not come from the capital costs. Nor does it come from the need to dispose of old equipment or to part ways with the existing vendor.

What is really difficult is the migration of multiple terabytes of data that reside in an existing archive. This may seem puzzling. We can store and retrieve DICOM images, so why can’t we easily retrieve DICOM objects? Many PACS store DICOM attributes in proprietary database tables, reassembling the DICOM objects only when they are requested. Vendors do this because it optimizes system performance. Remember, DICOM was designed for the communication of images, not as a database format.

Typical database problems include irregularities in patient names. Is Homer Simpson the same person as Homer J. Simpson? What about Homer Simson, spelled without the p, who has a different identification number but the same birth date and the same address? Are they all the same person?

What about a head CT study that actually contains images of the head, chest, abdomen, and pelvis? What about studies that were entered into the database with incorrect order or request numbers? And what about studies that were stored on read-only memory but whose attributes were updated after the initial image acquisition? When those studies are read off the disc, they will come back with the older values in the DICOM headers.

There are numerous other examples, all with some sort of information mismatch. During the migration progress, each of these will need either manual intervention or processing through additional software.

As might be expected, interfaces present special problems. All interfaces between the new PACS and other information systems and imaging equipment will, at the least, need to be tested. In addition, a new round of interface license fees may be imposed by other vendors, for example, the RIS vendor.

The phasing out of old equipment can create another problem, particularly if the new PACS installation runs behind schedule. In our case, we had been observing archive failures resulting from mechanical problems in the existing jukebox. We didn’t fix the problems because we expected the new system to be in place before the existing system failed completely. Unfortunately, we missed the target date for installation of the new PACS. Archive failures began to occur with increasing frequency and began to affect clinical operation.

At that point, it was unclear who would handle problems with the existing system during changeover. The old system vendor was no longer under service contract, and the new system vendor was not enthusiastic about paying to repair a system it was going to replace. It took several months of negotiation with both vendors to get the situation resolved. In the end, we had support of both systems.

Recommendations

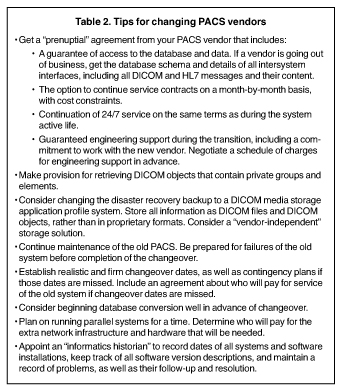

Based on our experience, it is wise to get a “prenuptial agreement” from the PACS vendor (Table 2). This agreement should provide for guaranteed access to the database and the data. If a vendor is going out of business, it is important to get the database schema from them before they shut down. Details of all intersystem interfaces are also needed, including all DICOM and HL7 messages and their content.

The agreement should include an option to continue service contracts on a month-to-month basis, with cost constraints. Service should be on the same terms as during the system’s active life. If service had been available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, it should continue at this level as long as the system is in clinical use.

The agreement should also provide for guaranteed engineering support during the transition, including a commitment to work with the new vendor. Such service will not be free of charge, but it is wise to negotiate a schedule of charges in advance.

No matter how information migration is managed-whether by the existing vendor, the new vendor, or a third party-provision should be made for DICOM objects that contain private groups and elements. Private DICOM groups are permitted in the DICOM standard, and many vendors use them. Ideally, a storage system will store these and return them on request. Determine how these will be migrated to the new system. Make sure the vendor does not simply discard private DICOM groups.

Establish realistic and firm change-over dates, as well as contingency plans in case those dates are missed. This should include an agreement about who will pay for service of the old system if changeover dates are not met.

Consider changing the disaster recovery backup to a DICOM media storage application profile system. Store all information as DICOM files and DICOM objects, rather than in proprietary formats. Consider using a vendor-independent storage solution that supports different vendors’ PACS. There are commercial vendors that provide such products, and some of the main PACS vendors can do so as well, upon request (and payment of the cost of such options).

Be prepared for failures of the old system before completing changeover to the new system, and know how to handle those failures. Do not ignore maintenance of the old system. Continue to check that backup systems are working.

Don’t count on reusing old PACS hardware. Not only is the old hardware likely to be obsolete, it will be needed when the old system is run in parallel with the new system during testing and startup. In addition, if the original PACS was acquired through an operating lease, the equipment must be returned to the original vendor unless a purchase agreement is negotiated.

Consider beginning database conversion well in advance of changeover. Set a target for the amount of data to be converted prior to the changeover, typically 1 to 2 years’ worth, with the rest converted on either an ad hoc basis or in a background process.

Determine who will perform database clean-up and how it will be paid for. If health system staff will be doing the clean-up, consider negotiating a charge-back rate to cover labor.

Considering having a database survey done ahead of time to determine how many problems exist in the database. This will provide perspective on how difficult the changeover is likely to be.

It will likely be necessary to run parallel systems for a while. Determine who will pay for the extra network infrastructure and hardware that may be needed to support a network that is twice its usual size.

If the change in PACS is a result of a decision by the health system or hospital administration, make sure they are aware of the full costs associated with making the change and are willing to support those costs.

Finally, appoint an “informatics historian” who will record the dates of all systems and hardware installations, keep track of all software version descriptions, and maintain a record of problems, as well as their follow-up and resolution. Such records are extremely valuable and have saved some institutions significant expenses on service contracts.

Conclusion

Adding a PACS to an existing enterprise is not a trivial endeavor. It requires knowledge and planning, chiefly with regard to interfaces and data flow. It is possible to minimize the negative impact of a PACS addition, but it is difficult to completely eliminate it. A change in PACS vendors is, without question, painful. The most effective way to minimize the pain is to thoroughly plan for the change and prepare for all that it will entail.

Related Articles

Citation

Avoiding pitfalls in adding to a PACS or changing PACS vendors. Appl Radiol.

December 14, 2008