3D Printed Models May Help Babies with Hip Dysplasia

Mechanical engineering students at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University are working on a 3D printed model project that may help babies born with hip dysplasia, a condition where the hip socket is shallow or ill-shaped, resulting in pain and worn out joints. Six undergraduates and one PhD student are combining their efforts across various areas of research to tackle this condition, which affects two to three children per every 1,000 born, according to the International Hip Dysplasia Institute (IHDI).

Mechanical engineering students at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University are working on a 3D printed model project that may help babies born with hip dysplasia, a condition where the hip socket is shallow or ill-shaped, resulting in pain and worn out joints. Six undergraduates and one PhD student are combining their efforts across various areas of research to tackle this condition, which affects two to three children per every 1,000 born, according to the International Hip Dysplasia Institute (IHDI).

“As a graduate student, Tamara Chambers is currently developing an infant musculoskeletal model using motion-capture,” said Dr. Victor Huayamave, assistant professor of Mechanical Engineering and faculty advisor for the project. “Two undergrads are developing finite element models using CT (computed tomography) and MR (magnetic resonance) images. Another student is developing models from cadaveric images. A group of three is building a 3D model of an infant with hip dysplasia to help train medical professionals.

“The objective of the trainer is to improve the accuracy of medical diagnoses of DDH (Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip) and reduce the cost of current industry models,” said Pedro McGregor, a Mechanical Engineering senior who led the 3D manufacturing aspect of the work.

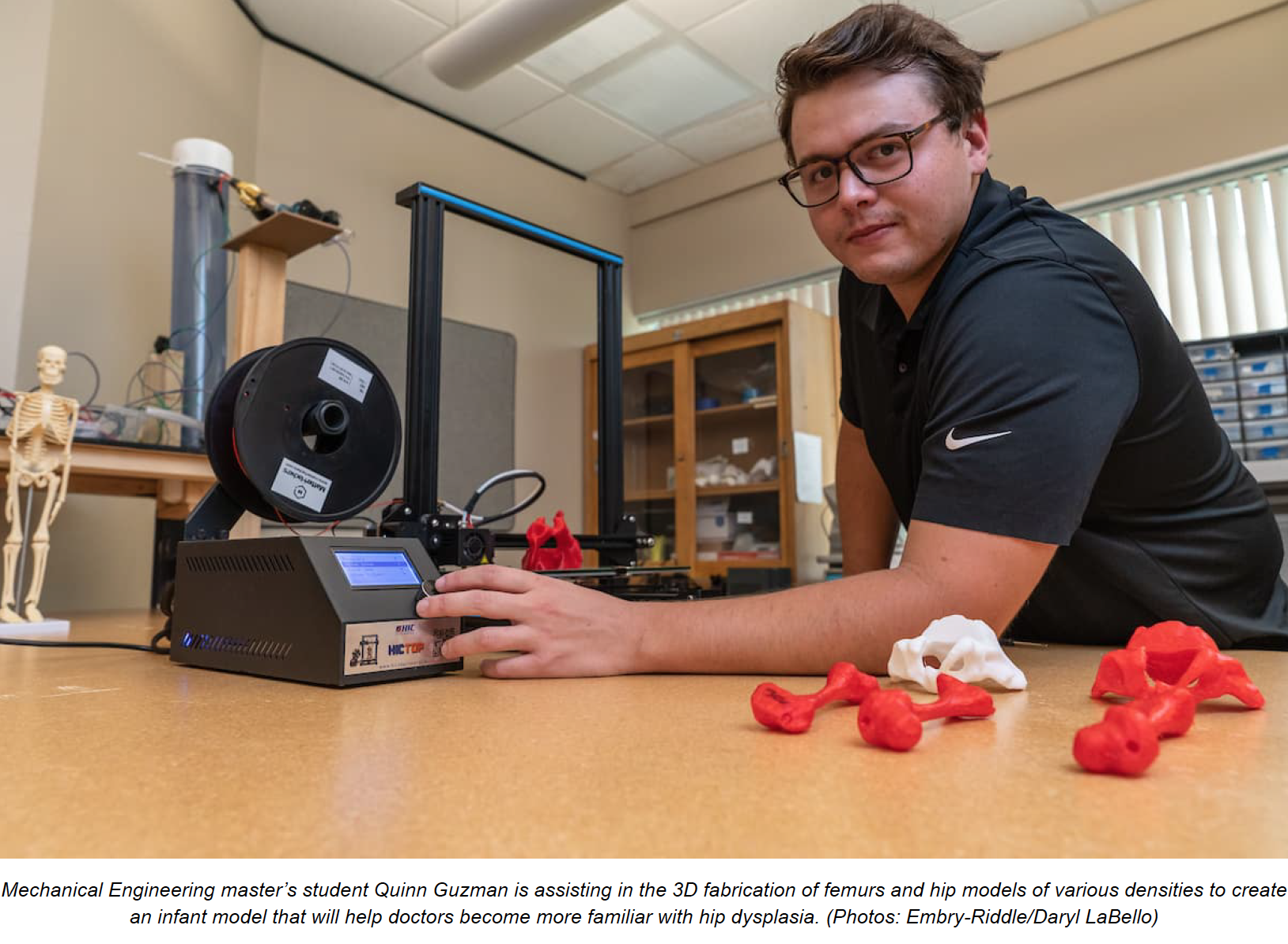

The 3D-printed models, inspired by a specimen from an anatomical museum, will help physicians in training understand what’s happening when they feel the movement of an unstable hip. The fabricated femurs and hips are of various densities and designed to mimic the fragility of infant bones during development. One of the biggest challenges the team encountered during their research, however, according to McGregor, is the lack of literature available on infant ligament properties — namely, stiffness and strength values.

“Because we came to a dead end, the team refocused our efforts on ensuring the ligaments would be able to hold the pelvis and femurs in place and be able to stretch without breaking when performing the medical maneuvers,” McGregor added.

Imitating an infant’s musculoskeletal anatomy, though, is much more complicated than simply scaling down a model of a fully matured human body.

“The goal is for this model to represent an infant and not an infant-sized adult,” said Chambers, a second-year Ph.D. in Mechanical Engineering student. “It will allow more researchers to study an infant’s growth and development within the first year of life.”

Aspen Taylor, a recent Mechanical Engineering graduate, led the component of the work in which segmented clinical images of infant bones were collected for 3D modeling and analysis.

“Catching hip dysplasia at an early age will allow doctors to solve the issues while the infant is still young, rather than the child growing older and it being harder the fix — or even possibly developing into other issues later in life,” she said.

Ultimately, the work can lead to a breakthrough in treatment options.

“What’s cool about research in this field is you provide one piece that someone else picks up and then they keep it going, and then the next person keeps it going, and then you have this really great end result,” said Quinn Guzman, another student involved in the work. “It would feel really rewarding knowing I contributed a little piece of that research that carried on to something that made a positive impact.”

But as Huayamave pointed out, hands-on research like this can be just as valuable to the students as it is for those their work is serving.

“All students are working on topics related to hip dysplasia but, at the same time, they are learning tools that can be translated to any engineering field,” said Huayamave. “This will help them tremendously in the future if any of them decide to change their research interest.”

Huayamave, along with Dr. Eduardo Divo, program chair and professor of Mechanical Engineering, has been contributing to hip dysplasia research since 2012, when he was a PhD student at the University of Central Florida (UCF).

Related Articles

Citation

. 3D Printed Models May Help Babies with Hip Dysplasia. Appl Radiol.

July 28, 2021