Worrisome and Incidental Signs on Knee Radiographs in Clinical Practice: Malignant Primary Bone Tumors and Benign Bone Lesions

Images

SA-CME credits are available for this article here.

Knee radiographs are ubiquitous studies interpreted by many radiologists in daily clinical practice, since X-ray is the most appropriate imaging modality for initial evaluation of nearly all knee signs and symptoms.1-5

In the first part of this series we explained how to identify a select group of difficult-to-diagnose traumatic pathologies and when to recommend additional imaging or clinical work up. We also discussed incidental signs of degenerative joint disease and a developmental anomaly that mimics worrisome pathology on radiographs.

In this second part of the series, we explain how to distinguish a select group of primary malignant bone tumors requiring further imaging and clinical workup from benign, tumor-like conditions. These entities can be a source of consternation, even for experienced radiologists.

Malignant Tumors

Chondrosarcoma

Chondrosarcoma, a malignant chondroid tumor, is the third-most common primary malignant bone tumor. It arises most often in middle-aged adults, commonly in the femur, and presents with insidious pain that progresses over time.6,7

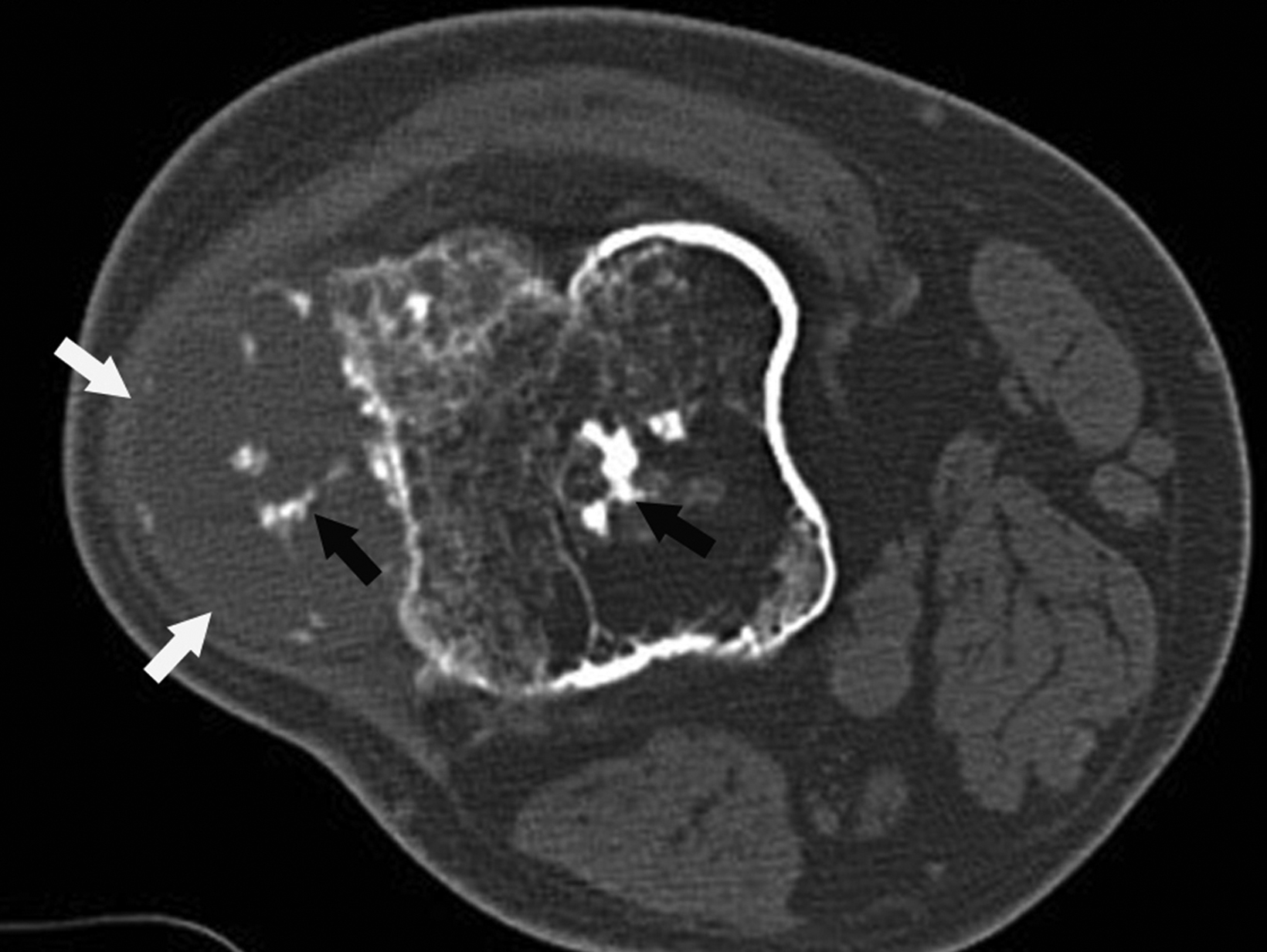

Typically, chondrosarcomas appear radiographically as ill-defined lytic lesions with internal chondroid matrix and bone destruction (Figure 1). Key features that favor chondrosarcoma over benign enchondroma include deep cortical endosteal scalloping, cortical bone destruction, and extra-osseous extension.6,8 Correlation with computed tomography (CT) imaging offers higher sensitivity for detecting chondroid matrix and evaluating extra-osseous extension. Primary management of chondrosarcoma typically consists of surgical intervention, as the tumor is relatively resistant to radiation and chemotherapy.6,7

Periosteal Osteosarcoma

A subtype of nonconventional “surface” osteosarcomas, periosteal osteosarcomas are rare, malignant neoplasms representing about 1% of all osteosarcomas.9,10 They most commonly affect adolescents and young adults and most often involve the metaphysis or diaphysis of the femur or tibia. Limb pain and swelling are the most frequent clinical symptoms.9,11

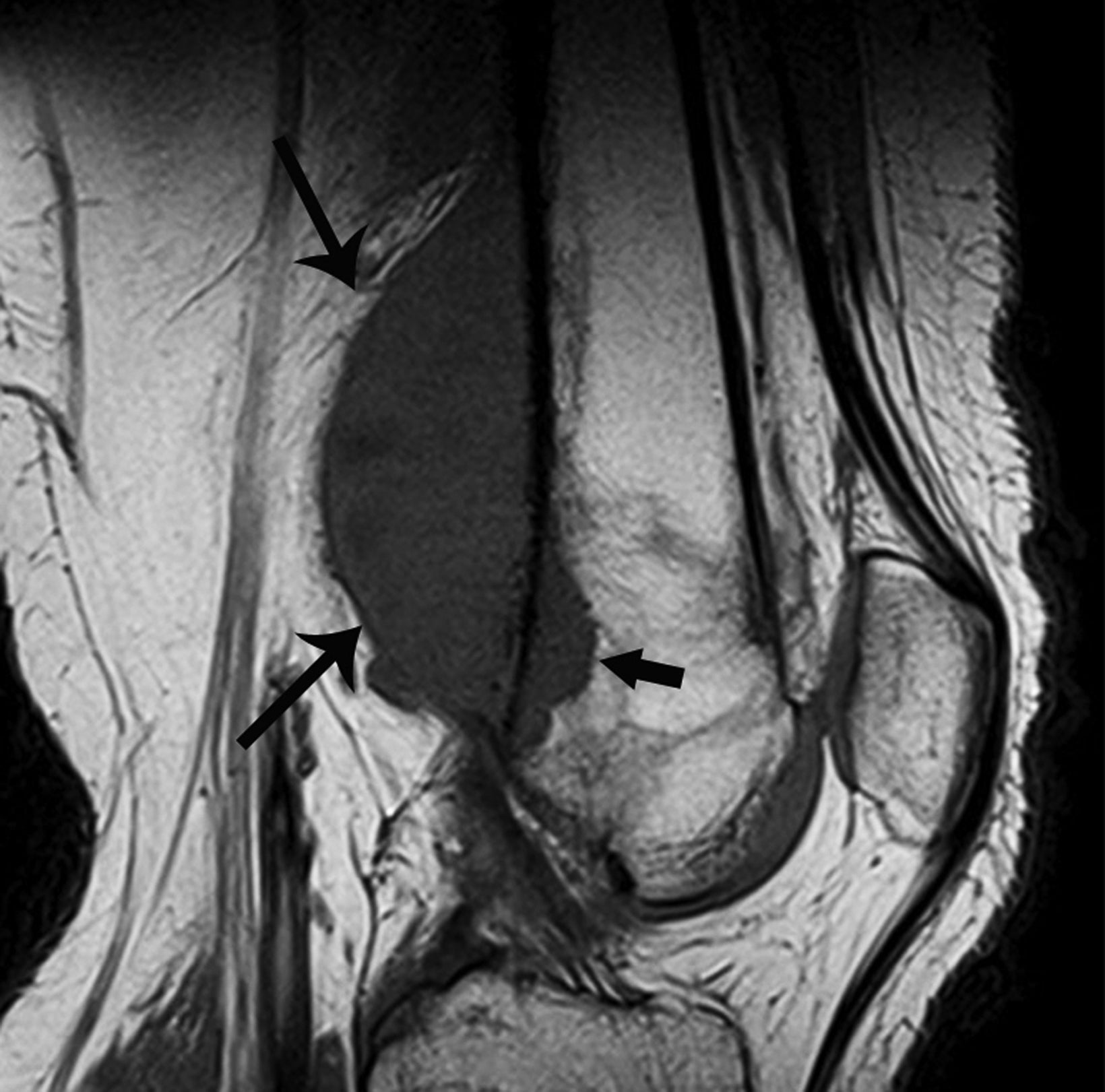

Radiographic features include an aggressive appearing periosteal reaction perpendicular to the cortex; cortical thickening and/ or erosion is also possible (Figure 2).9,10,12 Although signs of periosteal osteosarcoma may appear subtle on knee radiographs, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) typically reveals a large, extraosseous soft-tissue mass with intramedullary invasion in some cases.9-11 The absence of the more obvious cloud-like osseous matrix, sclerosis, and bone destruction usually associated with conventional osteosarcoma makes periosteal osteosarcoma a diagnostic challenge. Optimal treatment includes surgical resection with or without chemotherapy.9,11

Benign tumors

Chondroblastoma

Chondroblastomas are benign chondroid neoplasms that typically affect the epiphyses of the long bones. Afflicting mostly adolescents and young adults, they appear most often in the knee and represent nearly half of all cases. Symptoms/signs include pain, local tenderness, stiffness, and swelling.13-15

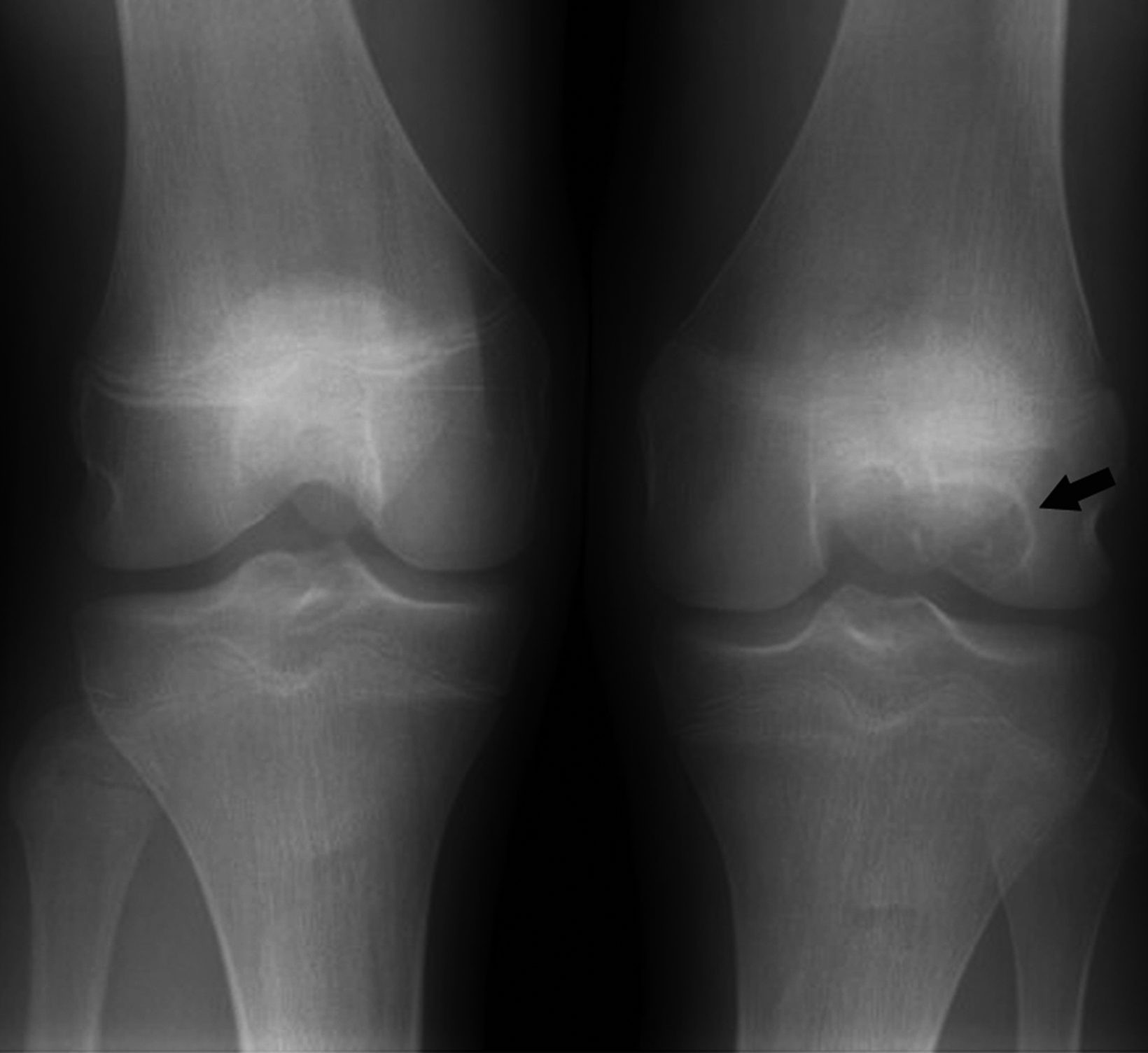

On radiographs chondroblastoma presents as an epiphyseal lytic lesion with lobular contours and well-defined sclerotic margins (Figure 3). MRI classically demonstrates intermediate signal on T1 images with variable signal intensity on T2 images and extensive edema in the adjacent bone (Figure 3). CT reveals sclerotic margins and internal chondroid matrix.13 Although considered benign, chondroblastoma usually requires surgical management.13-15 Local recurrence is uncommon but can be seen in cases of inadequate surgical management or malignant transformation.14

Osteochondroma

The most frequent bone tumors, osteochondromas represent 20-50% of benign tumors and 10-15% of all bone tumors.16 They occur most commonly in the long bones near the metaphyses about the knee. Osteochondromas can present as solitary lesions, or as multiple lesions in the setting of hereditary multiple exostoses, an autosomal dominant disorder.17 Most osteochondromas are asymptomatic and identified incidentally.

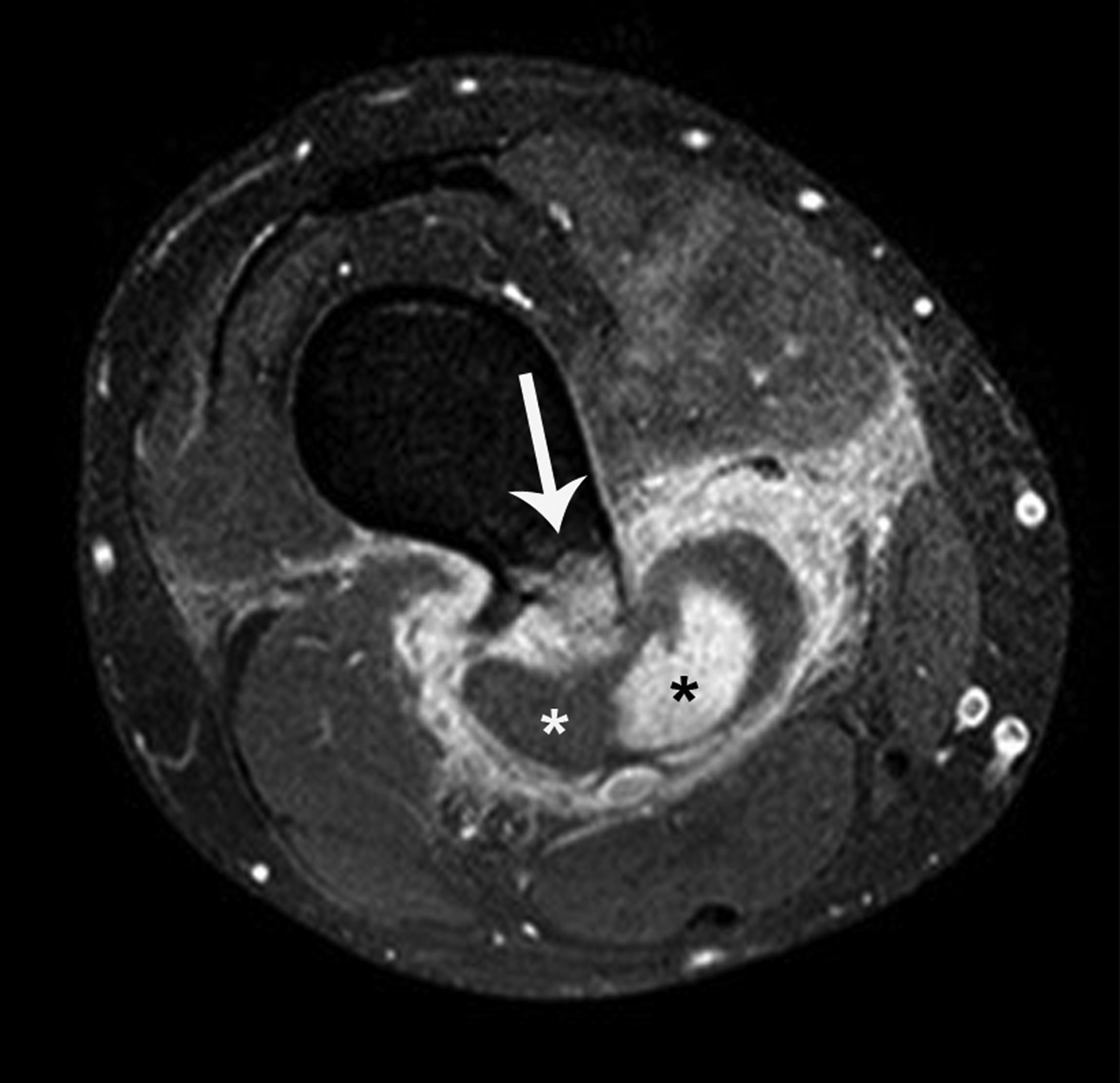

The typical pathognomic appearance of an uncomplicated osteochondroma on knee radiographs consists of an osseous excrescence with medullary and cortical continuity near the metaphysis that points away from the tibiofemoral joint.16 Although the majority of osteochondromas are incidental, uncommon complications include fracture, malignant transformation, and compression of adjacent soft tissue structures such as blood vessels and nerves (Figure 4). Bursal formation and bursitis resulting from the pressure effects of these tumors are additional soft-tissue complications. Another, more rare complication is benign osteochondroma-related pressure erosion owing to extrinsic compression on an adjacent bone. Surgical resection is usually reserved for osteochondromas that demonstrate thickening of the cartilage cap > 2 cm or bone destruction concerning for malignant transformation; severe mechanical complication; or cosmetic deformity.17,18

Incidental Signs

Enchondroma

Enchondromas are benign chondroid tumors frequently encountered about the knee.19,20 Typically, they are clinically silent and discovered during an unrelated workup for knee symptoms. The lack of pain directly referable to a discovered chondroid tumor is a subjective discriminator from chondrosarcoma.8

Enchondromas have a typical ring-and-arc mineralization pattern characteristic of chondroid matrix (Figure 5). Radiographic findings that distinguish them from chondrosarcomas include the absence of deep endosteal scalloping, cortical destruction, or extra-osseous extension. However, enchondromas may present with endosteal scalloping measuring less than two-thirds the width of the cortex.8,19 The majority of uncomplicated enchondromas do not require follow-up or treatment. The presence of symptoms referable to the lesion, pathologic fracture, increasing size, and bone destruction are indications for referral to an orthopedic oncologist.20,21

Nonossifying Fibroma

Common benign bone tumors, nonossifying fibromas typically occur in childhood and adolescence. They are usually asymptomatic and discovered incidentally.22-24

Nonossifying fibromas are well-defined lytic lesions with a bubbly appearance and thin sclerotic margins (Figure 6).25 They typically require no follow-up when asymptomatic, with most resolving spontaneously. Surgical management is usually reserved for cases that present with fractures discovered after the onset of bone pain.22,24

Incidentalomas

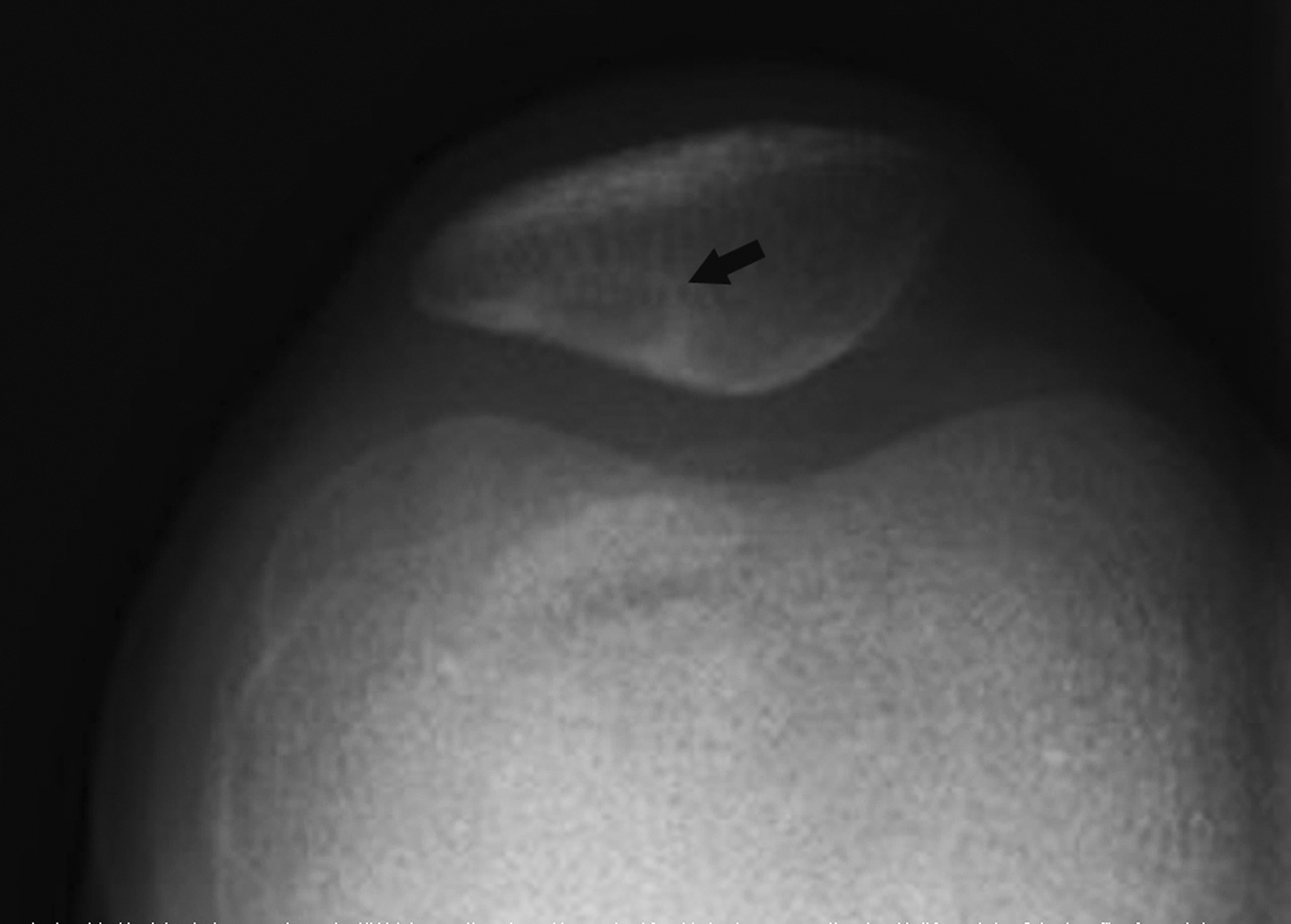

Dorsal Defect of the Patella

Dorsal defect of the patella is a benign developmental abnormality observed in about 1% of the population. Their etiology is not entirely understood but thought to be secondary to incomplete ossification.26,27

The keys to making a definitive diagnosis of this lesion and avoiding further workup are its location and appearance. Radiographically, the dorsal defect of the patella is a well-defined, round, lytic lesion with a sclerotic narrow zone of transition at the superolateral pole of the patella (Figure 7).28 Some cases “heal” over time with partial or complete resolution of the lucent appearance.27,29

Cortical Desmoid

Benign fibro-osseous lesions, cortical desmoids are most frequently located at the posteromedial aspect of the distal femoral metaphysis.30,31 They may be identified at any age but are most often encountered in adolescents and young adults. These lesions are described as the sequelae of avulsion injury caused by the medial head of the gastrocnemius or adductor magnus aponeurosis femoral insertion.32 Most cases are asymptomatic.33,34

Oblique knee radiographs usually provide optimal visualization of cortical desmoids, which appear as small, radiolucent, saucer-shaped lesions or areas of cortical roughening at the posteromedial cortex of the distal femoral condyle (Figure 8).33 The location and classic appearance, in the absence of any additional signs of bone destruction, should allow for confident diagnosis without requiring additional follow-up or intervention. Cortical desmoids have been reported to resolve spontaneously.33,34

Pellegrini-Stieda Lesion

The Pellegrini-Stieda lesion is a benign posttraumatic focus of mineralization that may mimic a bone tumor. Pellegrini-Stieda lesions classically occur at the medial femoral condyle after a presumptive traumatic insult related to the ligamentous structures, including the origin of the medial collateral ligament. Patients typically present with ongoing pain at the medial knee.35-37

On radiography, Pellegrini-Stieda lesions typically appear as dense linear or dystrophic mineralization along the proximal course of the medial collateral ligament (Figure 9). Comparison with radiographs performed at the time of injury typically demonstrate an absence of the lesion, since the posttraumatic soft-tissue mineralization may take weeks to months to appear radiographically. Most cases are managed conservatively, with surgical intervention rarely necessary.35-38

Conclusion

Knee radiography is commonplace in daily clinical practice. Knowledge of worrisome signs related to less-often encountered malignant or problematic primary bone tumors informs radiologists when to recommend additional imaging and intervention. Familiarity with the radiographic features of benign tumors and tumor-like conditions provides for confident diagnosis and peace of mind when no additional workup is required.

References

Citation

M W, G M, I K, DL D. Worrisome and Incidental Signs on Knee Radiographs in Clinical Practice: Malignant Primary Bone Tumors and Benign Bone Lesions. Appl Radiol. 2023; (2):8-15.

March 7, 2023