Study Finds Larger Warning Labels Linked to Lower Desire to Consume Alcohol

Images

In a groundbreaking study, young adult men who viewed larger, picture-based alcohol warning labels experienced a lower activation of the reward circuits in their brains compared to viewing more familiar small-text warnings. These findings could inform more effective messaging on alcohol-containing beverages and advertisements.

Despite recommendations from the World Health Organization and European Commission that warning labels be included on alcoholic products, few countries have implemented alcohol warning policies comparable to their approach to tobacco. Alcohol warnings are typically small, text-only messages. Research has been equivocal about their impact on drinking and whether incorporating pictures would increase their effectiveness, in part because most studies have relied on participants’ self-reported reactions. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has demonstrated variations in brain activation in response to varying types of tobacco warnings, including impacts that may be linked to smoking cessation. For the study in Alcohol: Clinical & Experimental Research, investigators in France used fMRI to compare young men’s reactions to different formats of alcohol warnings and how those related to self-reported responses.

The researchers worked with 74 men aged 18-25 who met the criteria for moderate or high risk of alcohol misuse. They tested two alcohol warnings custom-designed by an advertising agency. The message read, “One out of four drivers killed in a drink-driving accident is an 18 to 24 year old person.” One warning used a typically small text-only format. The other used larger text, in red, and showed the bloody face of a young man. The participants underwent fMRI while viewing beer, vodka, and whisky advertisements. They viewed 96 advertisements with text-only warnings and 96 with larger warnings with pictures. They also viewed 96 images of water advertisements without warnings. To each image, they answered whether the ad made them want to consume the product. The researchers used statistical analysis to compare self-reported and fMRI responses to different advertisements.

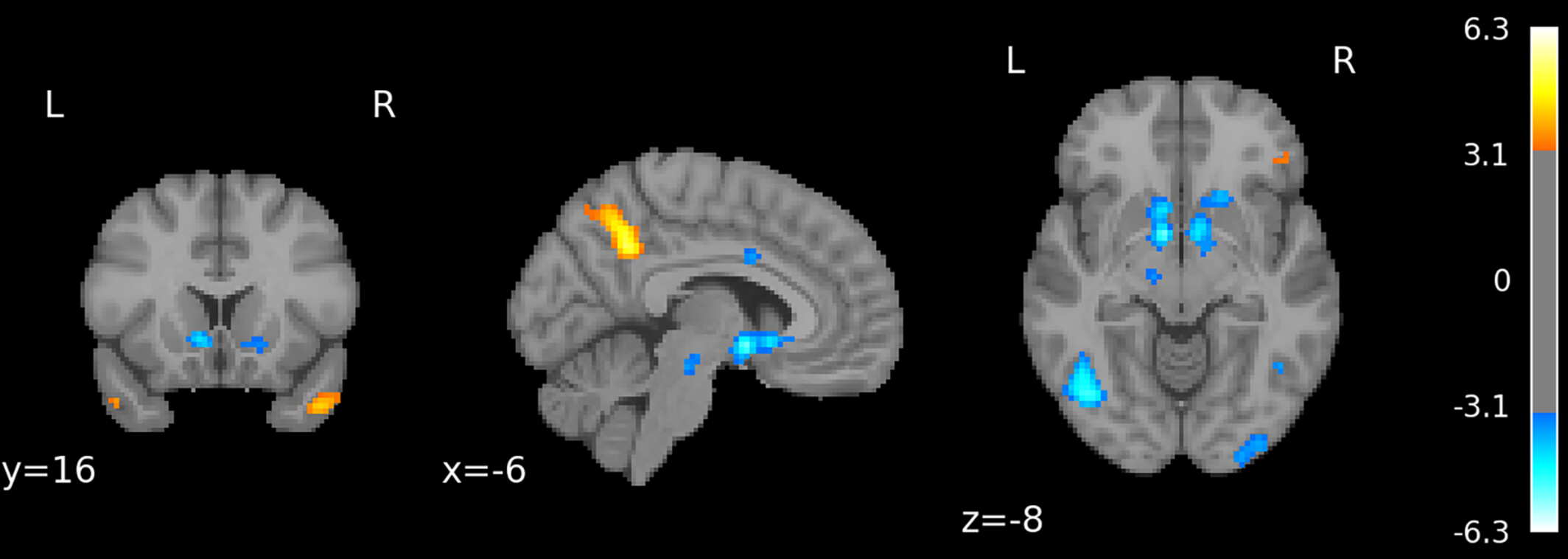

The young men reported a stronger desire to consume alcohol products that came with a small text-only warning. The larger warning, including the image, significantly reduced their reported desire to drink. The fMRI measures were aligned with these self-reports. Labels that included larger warnings and images generated more intense activation of brain regions involved in self-reflection, responsibilities, social or contextual focus, and processing emotionally salient stimuli. The warnings containing images were also linked to reduced activations in brain regions associated with reward, compared to the smaller text-only warnings. The participants expressed a greater desire to consume the water brands than the alcohol products.

The study suggests that larger warning labels, including pictures, are more effective drinking deterrents than typical small-text warnings and may reduce the persuasive effects of positive social content in some alcohol advertisements. The findings are similar to those of fMRI studies of tobacco warning labels. They offer neuroimaging-based evidence for designing labels that can effectively reduce dangerous drinking. The study did not adjust for participants’ smoking behavior, which could have influenced blood flow in the brains, nor assess their alcohol use following the fMRI session. Additional research is needed to test warnings related to other messages.