Solid Pseudopapillary Tumor of the Pancreas

Case Summary

A teenager presented to the emergency room after a motor vehicle collision and 5 weeks following Caesarean-section. The chief complaint was of left lower-quadrant abdominal pain. CT showed no traumatic injury but identified a pancreatic tail mass. Subsequent laboratory testing revealed normal lipase and cancer antigen 19-9 levels.

Imaging Findings

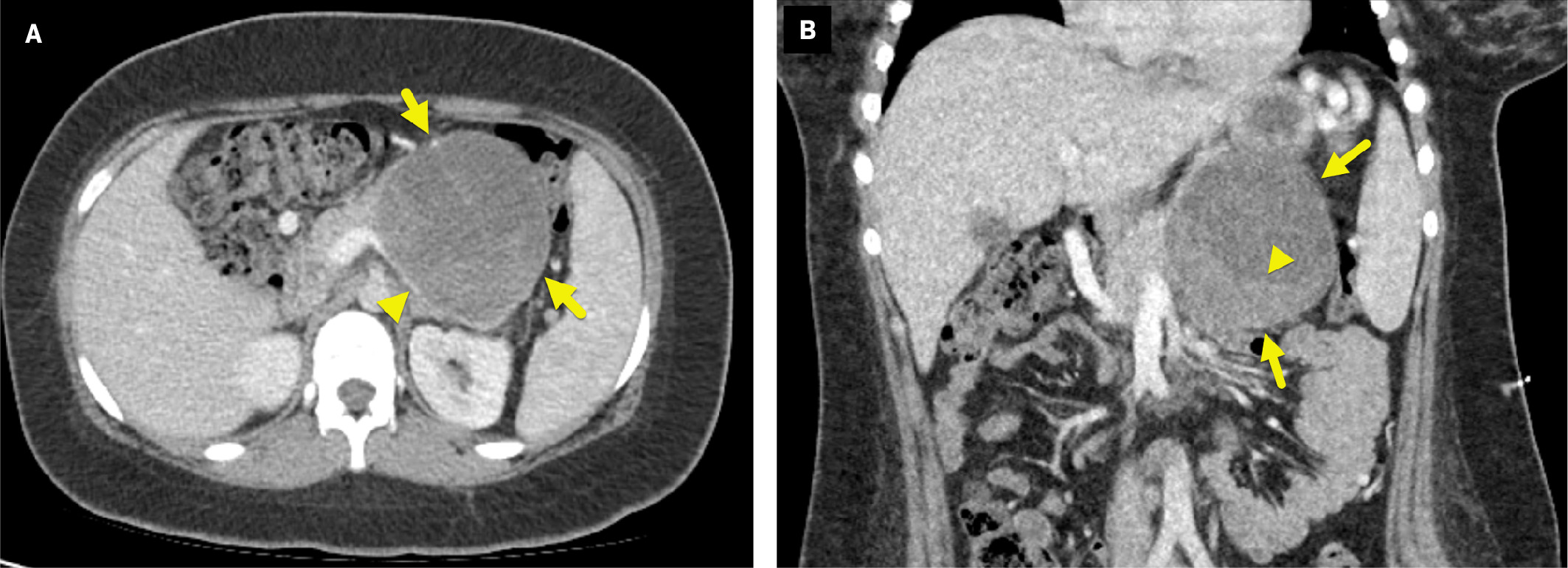

CT imaging ( Figure 1 ) showed an oval, well-circumscribed, 9.5-cm mass arising from the tail of the pancreas. The mass had a heterogeneous appearance with solid and cystic regions. It compressed the splenic vein, causing large splenic collateral vessels.

Axial (A) and coronal (B) contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen shows a mass (arrows) arising from the tail of the pancreas. The mass compresses the splenic vein (arrowhead in A) and has a solid, enhancing component posteriorly and inferiorly (arrowhead in B).

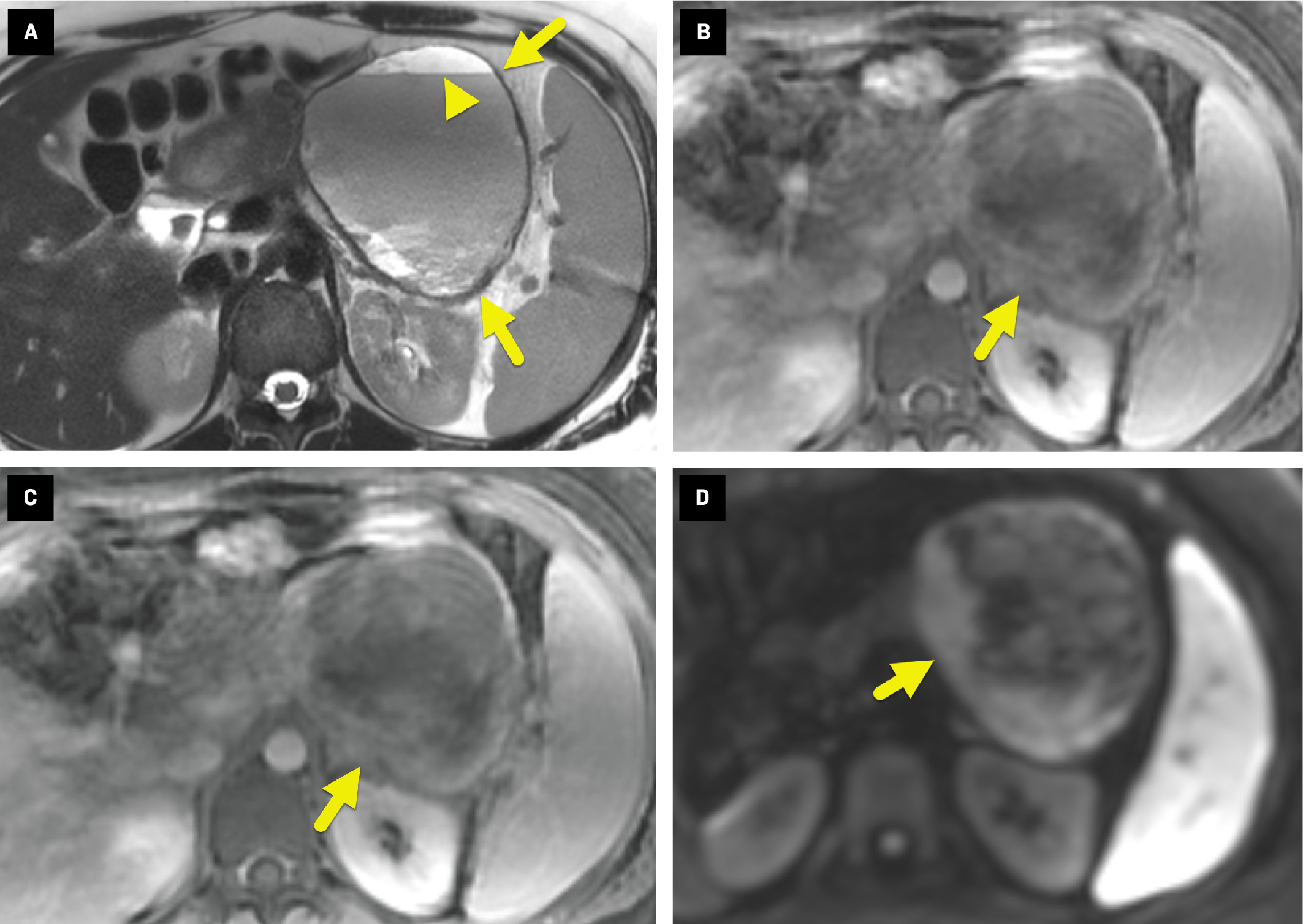

On MRI ( Figure 2 ), the mass appeared heterogeneous, with layering hemorrhage on T2-weighted images. Postcontrast images showed mild enhancement of the irregular soft-tissue component. The areas of enhancement also displayed restricted diffusion.

Axial T2-weighted MRI without (A) and with (B) fat suppression shows a heterogeneous pancreatic mass (arrow). The mass has layering fluid/debris within the cystic component (arrowhead in A), a heterogeneous posterior solid component, and does not contain fat. Axial T1-weighted dynamic spoiled gradient echo sequence (C) obtained 4 minutes after contrast administration shows mild enhancement (arrow) of the solid component of the mass. Diffusion-weighted sequence (b-value = 800) (D) shows restricted diffusion (arrow) in the enhancing portion of the mass.

Diagnosis

Solid pseudopapillary tumor (SPT) of the pancreas.

Differential diagnosis includes mucinous cystadenoma, mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, pancreatoblastoma, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor.

Discussion

An SPT of the pancreas is a low grade neoplasm of the exocrine parenchyma characterized by heterogeneous components of a cystic and/or solid nature.1 The latter characteristic had given rise to various names commonly used in the literature.2 Such names include solid and cystic acinar tumor, papillary epithelial neoplasm, solid pseudopapillary epithelial neoplasm, and Gruber-Frantz tumor.1, 3 - 6

Solid psuedopapillary tumors of the pancreas have a relatively low incidence, accounting for 1% of pancreatic neoplasms, 6% of all exocrine subtypes, and 8 to 17% of pediatric pancreatic tumors, noting that pancreatic tumors are highly unusual in children.3, 5 This type of pancreatic neoplasm has a disproportionately high 1:5.3-10 male-to-female (M:F) ratio and typically occurs during the third decade of life.2, 5 - 8 Papavramidis et al showed that SPTs are more likely to be diagnosed in children.5 In their study, 22% of patients were diagnosed when younger than 19 years of age while only 6% of patients were diagnosed when older than 51 years.5

The predilection for the tumor to occur in young women suggests that reproductive hormones, such as estrogen, may play a role in the pathogenesis of SPT of the pancreas. This theory is supported by data showing that postmenopausal women with SPT have a smaller tumor size compared with premenopausal women.7 Also, pediatric series have reported M:F ratios between 1:1.75-6.5, lower than the ratio seen in adults.8

Incidental detection, as seen here, is relatively common. When symptomatic, patients typically present with vague abdominal pain, bloating, and discomfort.2 - 6, 9, 10 Other signs can include a palpable abdominal mass or more nonspecific presentations such as nausea, vomiting, and weight loss.6 Tumors in the pancreatic head may eventually cause obstruction and signs associated with biliary backflow and obstruction (eg, jaundice, pancreatitis).2 - 7

Diagnosis is usually made using fine-needle aspiration (FNA) guided by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS).3 Histological features of SPT include branching fragments with central capillaries and myxoid stroma. On microscopic examination, the cells are uniform and polygonal, with abundant cytoplasm containing oval, regular nuclei. Immunohistological markers have been used adjunctly for diagnosing SPTs of the pancreas. These tumors are strongly positive for vimentin, alpha-1 antitrypsin, and neuron-specific enolase.3, 4 Tumor cells from SPTs usually do not stain for chromogranin and synaptophysin, which help distinguish them from islet cell tumors. They usually do not stain for keratin, which can help distinguish SPTs from acinar carcinoma.4 This is important as SPT is often considered in the differential diagnosis based on imaging characteristics, but it is uncommon.4

On imaging, SPT is characterized by hemorrhage and cystic degenerative change; it can be cystic, cystic and solid, or a solid mass. On US, SPT typically appears as large and well-defined, with capsular integrity.1, 4 On CT, it is typically well-encapsulated, with heterogeneous density and contrast enhancement of peripherally located solid components.1, 4 On MRI, SPTs are usually heterogeneously hypointense on T1, and heterogeneously hyperintense on T2.1, 10 After contrast injection, there is patchy enhancement of internal components.1, 4 MRI is generally the imaging modality of choice as it can show hemorrhage, cystic degeneration, and integrity of tumor capsule, the classic features of pancreatic SPT.4

There is inconsistency in the literature regarding its most common location; some studies suggest that the body and tail of the pancreas are more common, whereas others have found that SPT occurs relatively equally in the head and tail.1, 4, 9, 10 The tumors are typically large at diagnosis, with an average diameter of 8 cm.9, 10 A systematic analysis that collected studies performed before and after the year 2000 found that the average size at diagnosis had decreased while the number of cases of pancreatic SPT had increased.10 These trends are thought to be due to earlier detection with improved imaging.

Solid pseudopapillary tumor typically has a good prognosis after surgical resection. However, malignant progression and fatal outcomes have been reported.3, 4 It is not clear what causes malignant or aggressive progression.4

Conclusion

An SPT of the pancreas is an exocrine parenchymal neoplasm characterized by cystic and/or solid components that usually affect young women of reproductive age. Patients most commonly present with abdominal pain and a palpable mass. Diagnosis is usually made using FNA guided by EUS.

These tumors are considered low-grade neoplasms with an overall good prognosis. Early recognition of characteristic imaging features on US, CT, and/or MRI can aid in diagnosis.

References

Citation

Perez, ES, Towbin AJ, Morgan D, Towbin RB. Solid Pseudopapillary Tumor of the Pancreas. Appl Radiol. 2024;(4):39 - 41.

doi:10.37549/AR-D-24-0021

October 1, 2024