Re-engineering radiology in an electronic world: The radiologist as value innovator

Images

Dr. Chang is a Professor and Vice-Chairman, Radiology Informatics, and Medical Director, Pathology Informatics, University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, and the Medical Director, Enterprise Imaging, for the University of Chicago Hospitals, Chicago, IL.

In radiology informatics and information technology (IT), we are constantly challenged to provide a sustainable infrastructure that supports the needs of the radiology department and enables imaging throughout the healthcare enterprise. In the early days, many of us thought that radiology informatics was defined merely by digital image management and its promise to eliminate X-ray film. Once we accomplished that goal, we realized that optimization of workflow was even more important.

Too often, electronic practice tools are viewed as turnkey solutions. In reality, installation of a picture archiving and communication system (PACS) or a speech recognition system will not fix a “broken” radiology practice. The improper application of electronic-based systems can make deficiencies in workflow even more glaring. Unless we are willing to dramatically re-engineer the radiology department and our own attitudes and practices, we will not only fail to successfully leverage and exploit these advanced imaging tools, we may threaten the perceived value of radiology and participate in its marginalization or commoditization.

From a strategic perspective, our true goal is to build a technology infrastructure that ensures the relevance and value of radiologists in taking care of patients. Those of us in informatics and IT need to incorporate into our strategic planning a view of radiologists as value innovators.

Value innovation

The concept of value innovation was first introduced by Michael Porter in his 1985 book, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance.1 Value innovation is the never-ending task of re-examining what we provide that is of value to our customers. We must always ask ourselves: Are we relevant? Do we add value? And we must continuously re-engineer our workflow and our attitudes to add that value.

In a modern economy, there are 2 ways to compete. If your product or service is perceived as a commodity—that is, undifferentiated from competing products or services—the only legitimate basis on which to compete is price. Toilet paper, for example, is a commodity.

Another way to compete is to provide a product or service that is perceived as having additional value that can be differentiated when compared with other products and services. An iPod (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA), for example, is perceived to have more value than other MP3 players.

The question is, as radiologists, are we providing a commodity that can be outsourced anywhere or are we providing true value? The answer depends on how we see ourselves and what kinds of service we provide. In arriving at that answer, it is important to ask customers what is important to them and how well we're succeeding in meeting those needs.

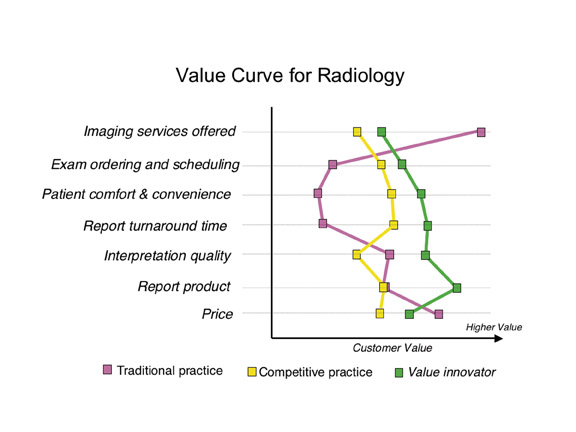

Once we have defined those axes of value, it is possible to plot a value curve. Figure 1 shows value curves for 3 different types of radiology practices. 2 The value curve for a typical academic radiology practice shows very high value in the number of imaging services provided. However, academic practices tend to fall short when it comes to other components that are valued by customers, such as examination ordering and patient comfort.

The services provided by a competitive, successful community-based practice are quite different from those provided by an academic practice, and they result in a characteristic value curve that is also different. The “competitive” practice may not deliver as many imaging services, but it excels in services that are perceived as being of value to the customer, including examination ordering and scheduling, patient comfort and convenience, and report turnaround time.

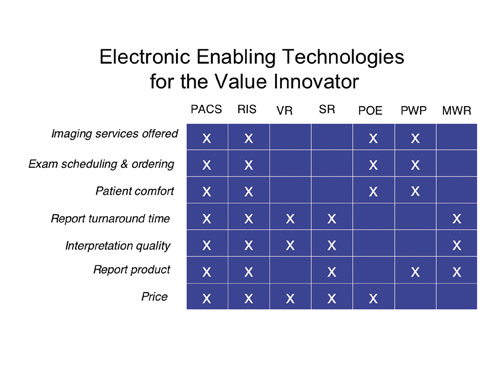

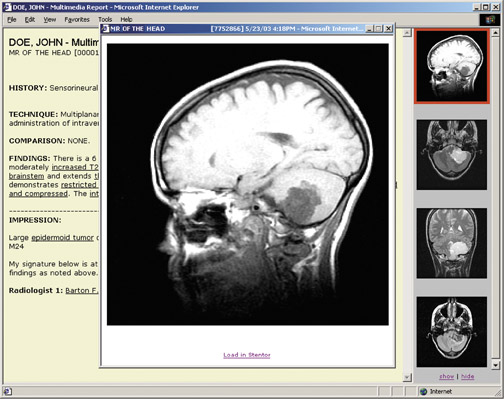

True value innovators go even further, identifying where they are on the value curve, where they want to be, and the gaps in between. Then, and only then, do they acquire technology that best suits and addresses those gaps, whether it be PACS, teleradiology, a radiology information system (RIS), voice recognition, structured reporting, Web-based physician order entry, multimedia Web reports, or patient Web portals(Figure 2).

The iPod effect

Before identifying gaps in value, it is important to understand who the customer is. In the context of radiology, our customers are our referring physicians and, ultimately, our patients. Today, patients are active health consumers, and, like other consumers, their characteristics have changed over the last 10 to 15 years. Let’s call it the iPod effect.

From functional point of view, the iPod could be considered an inferior product. For example, it doesn't come equipped with FM radio, and it locks users into a particular application, iTunes. Yet the totality of the experience is viewed as seamless, attractive, and very positive. The reason the iPod is successful is that it addresses 3 major drivers of the modern-day consumer-characteristics that drive our modern-day healthcare consumer as well.

The first driver of the iPod effect is real-time delivery, or “I want it now.” In the past, if customers ordered a music CD and received it in the mail a few days later, they were happy. Then it became possible to place an online order before midnight and receive the CD by express delivery the next day. Now, we can go to iTunes and download music onto the iPod immediately. Real-time delivery of service and product is a critical driver and one of the reasons the iPod has been so successful.

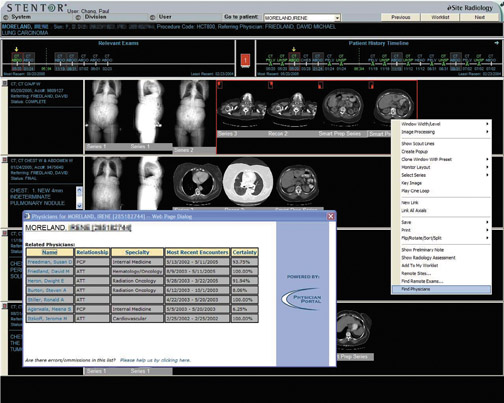

When it comes to medical care, that same expectation is valid. Many of us in hospital-based radiology practices have confronted the increasing demand to provide same-day service. A patient comes in in the morning for a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study or a positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scan, and the patient wants the interpretation in his or her oncologist’s hands that afternoon, so therapy can begin immediately (Figure 3). Clearly, the drive for real-time delivery of service is going to continue and is one of the reasons certain technologies such as speech recognition have become so important.

The second iPod characteristic is no-compromise service. From the elegant interface to the seamless integration with an industry-leading, comprehensive iTunes library, the iPod offers users a listening experience that is without peer.

In healthcare, patients have developed similar expectations. In the past, there was an asymmetrical distribution of healthcare information-that is, the doctor always knew more than the patient. This is no longer the case. Who is more motivated to know everything about a disease than the person who has the disease? With the resources available on the Web, many patients are extremely knowledgeable. After all that research, they want optimized, no-compromise service. As a result, we can no longer differentiate ourselves as physicians who add value by simply knowing more than our patients. Instead, we must take on the role of consultant and manager, becoming the person who helps shepherd the patient through a complex process. Patients will no longer settle for second-best.

The last driver is personalized service. With the iPod, we can select our own music. We no longer have to listen to someone else’s selection on the radio. With amazing advances in genetics and proteomics, physicians will be able to provide customized therapy for patients. That same driver is going to be relevant in radiology. For example, optimized image protocols that are tailored to the specific patient will require much more capable integration of information systems.

Information throughput

Another major driver in radiology is the concept of pay for performance, or “no outcome-no income.” Can radiologists successfully play this game? I believe we can. However, critical requirements for success will include massive improvements in efficiency, productivity, and cost-effectiveness—in other words, optimized information throughput.

Electronic-based technology and informatics can be important enablers of value innovation, if we’re willing to re-engineer our processes. When it comes to improving efficiency in information throughput, we must go beyond such simple measures as enhancing patient throughput or reducing report turnaround time.

The turnaround time that really matters encompasses the entire service chain. It spans from the time a physician decides to order a study to the time at which information is available from that study to help the clinician create a patient management plan. To truly improve turnaround time, we must re-evaluate examination ordering and scheduling, patient registration, examination acquisition, examination interpretation, report authoring, and report delivery.

Collaboration

It is clear that we must do away with film and paper. Instead, we must embrace electronic-based informatics systems. To do this, we need much better integration of electronic information systems and modalities within those systems. To date, a lack of integration is one of vendors’ biggest failures.

Time-motion studies repeatedly show that technologists waste too much time typing information from one electronic system to another. We also need greater integration in communicating context. It makes no sense for technologists to have to tell a RIS that they have completed a study. “Performed procedure” steps and other kinds of technology can do that automatically.

In addition, we will need to make major improvements in how we communicate. Simply sending out reports in a timely fashion willno longer be adequate. We must be much more engaged and collaborative.

In considering the difference between communication and collaboration in radiology, it is useful to think about the evolution of the Web. Radiologists typically use a PACS the way people used an old-fashioned Web 1.0 application. We sit in a dark room, and information or images come to us. Our clinicians are not interacting with us, and we’re not collaborating with them. This is one reason radiology can be easily commoditized and marginalized.

Today, kids don’t use the Web to passively receive information in isolation from one another. They use such applications as Skype (SkypeTechnologies, Luxembourg), instant messaging, MySpace (MySpace, Inc., Los Angeles, CA), and YouTube (YouTube, LLC, San Bruno, CA) to foster virtual collaboration and active participation.

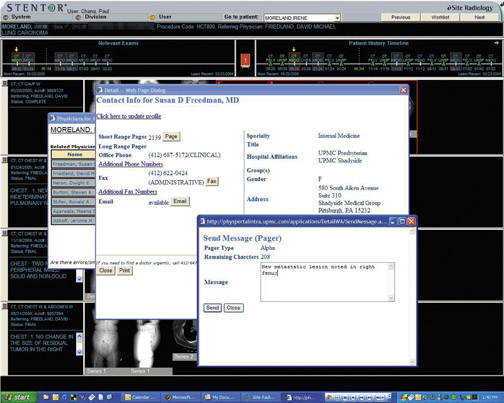

Radiologists and vendors must re-evaluate applications from this Web 2.0 perspective, re-engineering them in a way that fosters collaboration with clinicians (Figure 4). The goal is to match the appropriate communication method to a specific clinical context. Messaging, Web conferencing, multimedia reports, and other electronic communication models can all be very helpful.

Conclusion

Radiology must be willing to continuously re-engineer and reinvent itself to fully exploit electronic technology. Information systems canplay a significant role in helping radiologists to evolve from being simple providers of information to true collaborators. If we choose to make this transition, we will avoid being marginalized and commoditized. Instead, we will be able to show that we add true value to patient care.