Radiological Case: Infarcted splenule

SUMMARY

A 58-year-old female with a medical history significant for asthma, diabetes and hypertension presented to the emergency department with left flank pain of 1 day’s duration. She also reported a 100.8°F fever but denied nausea or vomiting. On physical exam, she was afebrile with an occasional cough, 4/10 pain, and mild abdominal tenderness to palpation in the left upper quadrant. There was no CVA tenderness or peritoneal signs. She denied any trauma. Her white blood cell count was slightly elevated (12,500) with an increased neutrophil count (10,000/ul). Due to the patient’s continued pain, a contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained.

IMAGING FINDINGS

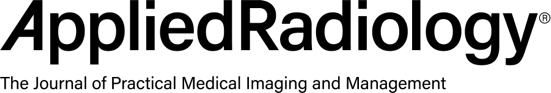

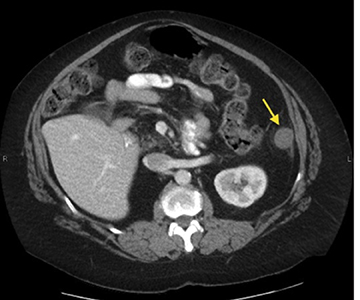

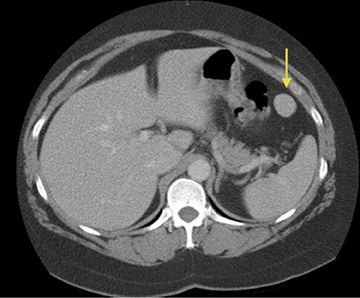

Contiguous axial CT images of the abdomen and pelvis were obtained using non-ionic contrast material, and coronal and sagittal reformats were also provided. These images revealed a hypoattenuating, round, soft-tissue mass inferior and anterior to the spleen with mild inflammatory changes of the surrounding mesenteric fat (Figure 1). On coronal and sagittal reformats, there was also a curvilinear structure extending superiorly from the mass which could be traced back to the splenic artery, likely representing a splenic arterial branch (Figures 2A, 2B). This mass had been seen on a chest PE with contrast study 12 years prior and had similar contrast enhancement patterns and Hounsfield unit values as the spleen, compatible with a splenule (Figures 3A, 3B).

DIAGNOSIS

Infarcted splenule. Differential diagnoses: neoplasm, tuberculoma, infectious abscess.

DISCUSSION

Splenules, or accessory spleens, are congenital foci of normal splenic tissue that are separate from the main body of the spleen.1 They are not uncommon, and are often incidentally found on CT scans and other abdominal imaging studies. A retrospective review by Mortele et al of 1000 patients found that 16% had splenules on contrast-enhanced CT imaging.2 They most commonly appear posterior and medial to the spleen (22%) and are well-marginated, round masses that enhance homogenously on contrast-enhanced imaging.2 Vascular supply is usually from the splenic artery.3

Splenules are typically asymptomatic, but various clinical complications such as hemorrhage, rupture, and torsion in pediatric patients have been described.4 Symptoms typically include intermittent left upper quadrant pain due to ischemia in torsed splenules, but they can progress to an acute abdomen in more severe cases.

It is important to differentiate splenules from wandering spleens, although infarction of the two may present with similar imaging findings. A wandering spleen occurs because of laxity or absence of the suspensory ligaments of the spleen, leading to hypermobility.5 While not a common entity, this occurs more often in children rather than adults. Failure of the splenic tissue to enhance on contrast-enhanced CT indicates infarction in these cases. Similarly, the splenule on our exam appeared hypoattenuating compared to the spleen, suggesting ischemia and infarction given that the splenule previously enhanced like the spleen on the prior CT exam. The surrounding mesenteric stranding also supported splenule infarction.

It is important to be able to distinguish infarcted splenules from other causes of acute left upper quadrant pain which require surgery as they represent an abnormal cause of abdominal pain that can be managed nonsurgically. In this case, the patient was sent home with analgesics and made a full recovery.

CONCLUSION

In this case, CT was used to diagnose an infarcted splenule. While rare, it is important to know the radiological and clinical signs in order to keep a high index of suspicion for infarcted splenule given the correct clinical scenario in order to prevent unnecessary surgery and facilitate correct, conservative treatment.

REFERENCES

- Freeman JL, Jafri SZ, Roberts JL, Mezwa DG, Shikhoda A. CT of congenital and acquired abnormalities of the spleen. Radiographics. 1993;13:579–610.

- Mortele KJ, Mortele B, Silverman SG. CT features of the accessory spleen. Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1653–1657.

- Grinbaum R, Zamir O, Fields S, et al. Torsion of an accessory spleen. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31:110–112.

- Mendi R, Abramson LP, Pillai SB, Rigsby CK. Evolution of the CT imaging findings of accessory spleen infarction. Ped Radiol. 2006;36:1319-1322.

- Nemcek AA JR, Miller FH, Fitzgerald SW. Acute torsion of a wandering spleen: Diagnosis by CT and duplex Doppler and color flow sonography. Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:307-309.