Pancreatic Divisum in Children

Case Summary

A teenager presented with chronic abdominal pain and severe nausea. The patient previously underwent surgery for median arcuate ligament syndrome, with persistent chronic abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting as well as and progressive weight loss. One month prior to presentation, the patient was diagnosed with pancreatitis and dilated intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts with a common bile duct (CBD) stone on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Additionally, pancreas divisum was noted on the MRCP.

Diagnosis

Pancreatic divisum (PD).

The differential diagnosis for PD includes gallstones, microlithiasis, medication-induced pancreatitis, autoimmune metabolic disorders, and other anomalies such as annular pancreas.1

Imaging Findings

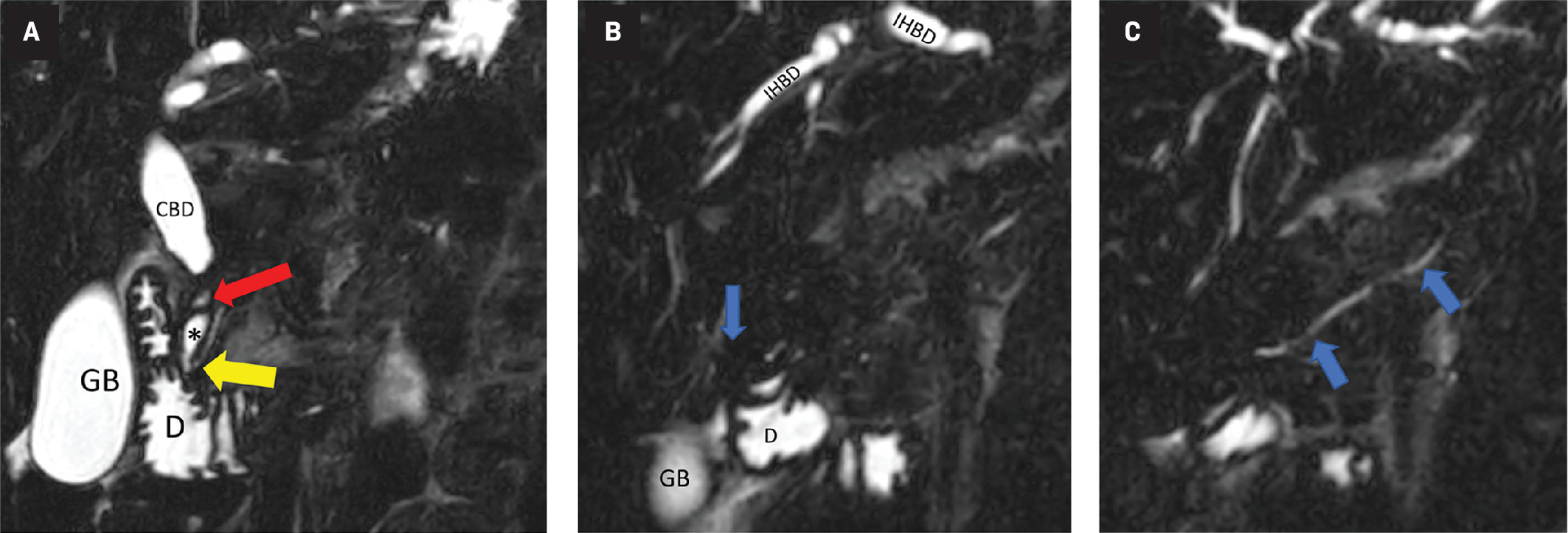

Coronal MRCP sequence images ( Figure 1 A-C) show that the ventral (Wirsung) duct joins the CBD and drains into the duodenum via the major papilla. There is dilatation of the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts as well as a stricture of the CBD. The distal dorsal pancreatic duct (Santorini) is shown emptying into the duodenum via the minor papilla, dorsal pancreatic duct. PD is diagnosed when the ducts of Wirsung and Santorini fail to fuse.

Posterior to anterior images. All images are a coronal MRCP sequence. The ventral (Wirsung) duct (A, yellow arrow) joins the CBD and drains into the duodenum via the major papilla. There is dilatation of the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts as well as a stricture of the CBD (red arrow). The distal dorsal pancreatic duct (B, Santorini) empties into the duodenum via the minor papilla (blue arrow), dorsal pancreatic duct (C, blue arrows). Pancreatic divisum is diagnosed when the ducts of Wirsung and Santorini fail to fuse.

Discussion

PD is a congenital malformation of the pancreatic ducts, with a reported prevalence of approximately 10% in the general population. The anomaly is usually identified at autopsy with MRCP or with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) studies.2 The clinical significance of PD has not been clearly defined, with more than 95% of these patients found to have PD incidentally, lacking pancreatic symptoms.3 However, in the INSPPIRE (INternational Study Group of Pediatric Pancreatitis) cohort of children with acute recurrent or chronic pancreatitis, 14.6% were found to have PD, which is more than the general population.4

The embryological development of the pancreas starts around the fifth week when the pancreas starts as ventral and dorsal pancreatic buds. The ventral pancreatic bud originates in the hepatobiliary system, rotates, and fuses with the dorsal pancreatic bud originating in the foregut. The ventral bud contains the duct of Wirsung, and the dorsal bud, the duct of Santorini. As the CBD rotates, the 2 components fuse to form the main pancreatic duct of Wirsung, opening into the major papilla in the CBD. An accessory duct of Santorini from the dorsal bud can either atrophy or persist as an accessory duct.5

PD arises when the 2 ducts fail to fuse. The degree of this failure can result in several subtypes: (1) In classic PD (major variant), there is no communication between the 2 ducts; the ventral duct opens into the major papilla and the longer dorsal duct opens into the minor papilla. (2) When there is incomplete PD (minor variant), the anatomy is similar to the classic PD but with a small communication between the 2 ducts. (3) In reverse PD (rare variant), the duct of Santorini does not communicate with the main duct or the minor papilla.3

Due to most patients with PD being asymptomatic in the absence of additional risk factors such as cholelithiasis, cystic fibrosis, medications (most notably valproic acid and asparaginase), or mutations in genes encoding pancreatic enzymes, screening asymptomatic children is not recommended except for children with cystic fibrosis identified with an abnormal sweat chloride test.1 Young children with pancreatitis, especially infants and toddlers, present with generalized abdominal pain and irritability whereas adolescents and adults present with severe epigastric pain radiating to the back.1 According to the INSPPIRE criteria, a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis in pediatric patients must meet 2 of 3 criteria: (1) abdominal pain, (2) serum lipase or serum amylase level 3 times the normal level, and (3) characteristic findings of acute pancreatitis on imaging.6, 7 Of note, serum lipase is a more reliable laboratory marker since amylase production is physiologically low in infants.1

Patients with asymptomatic PD require no further workup and treatment. Those with minor or infrequent symptoms are treated conservatively with a low-fat diet, analgesics, anticholinergics and, if necessary, pancreatic enzyme supplementation. Children with recurrent or severe symptoms warrant MRCP for evaluation and possible treatment of a stenotic minor papilla orifice or obstructive causes. Treatment of PD can include an endoscopic sphincterotomy, which is less invasive than a surgical sphincteroplasty.3, 7 Therapy should be based on morbidity, patient preference, and local institutional expertise.3

If a patient with PD presents with pancreatitis, oral feeding is recommended as soon as tolerated. If oral feeds are not tolerated or the required calories cannot be achieved in 72 hours, enteral tube feeding is recommended.8 Aggressive fluid replacement therapy is recommended in children for the first 24 hours.3 Analgesia should be provided when indicated, with an emphasis on nonopioid medications.1, 8 Endoscopic therapy for PD includes minor papilla endoscopic sphincterotomy, minor papilla orifice balloon dilation, and trans minor papilla duct stenting. Total pancreatectomy and islet auto transplantation is a surgical option to reduce the recurrence of chronic pancreatitis refractory to other therapies.3, 8

Endoscopic US can diagnose PD, with a sensitivity of 87% to 95% with secretin enhancement to better visualize the ducts by stimulating pancreatic secretions.3 Findings suggestive of pancreatic anomalies include the absence of the “stack sign” in which the distal CBD, ventral pancreatic duct, and portal vein run on a parallel axis in a normal pancreas. The presence of a “crossed duct sign,” in which the dorsal pancreatic duct crosses over the bile duct anteriorly and superiorly, indicates the presence of PD.3

Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT is recommended only in pediatric patients who are clinically deteriorating. CT will visualize acute and chronic changes such as pancreatic atrophy and fat replacement but will not detect subtle parenchymal changes.1 On contrast-enhanced CT, the findings are described as dorsal duct crossing anteriorly and superiorly to the distal CBD in the pancreatic head opening into minor papilla with a small ventral duct opening into the major papilla. CT sensitivity can be as low as 50% to 60% when there is pancreatic inflammation and is not desirable in childhood due to the radiation exposure.1, 3

ERCP is considered the gold standard for diagnosing PD and can be used in this therapeutic setting but is not recommended for diagnostic purposes alone due to its invasive nature.3, 8 MRCP is comparable to ERCP, and noninvasive MRCP is recommended for a suspected pancreatic ductal leak injury or suspected biliary tract abnormalities.8 Sensitivity and specificity increase with secretin-enhanced MRCP to 83% to 86% and 97% to 99%, respectively. MRCP findings can include a Santorinicele, described as a cystic dilation of the dorsal duct near the opening of the minor papilla.3 In addition to its lack of radiation exposure, MRCP is significantly more sensitive than CT for detecting chronic changes and irregularities of the pancreatic ducts and side branches.1

Conclusion

Although PD is a congenital malformation of the pancreas, pancreatitis is unlikely; however, there may be an increased risk. Imaging findings, including the crossed duct sign can diagnose PD. Patients should be treated for PD when they have associated severe or chronic pancreatitis.

References

Citation

Groth N, Towbin RB, Schaefer CM, Towbin AJ. Pancreatic Divisum in Children. Appl Radiol. 2024;(5):17 - 19.

doi:10.37549/AR-D-24-0015

October 1, 2024