Muscle Loss May Increase Dementia Risk

Images

According to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA), skeletal muscle loss is a risk factor for developing dementia.

Skeletal muscles make up about one-third of a person’s total body mass. They are connected to the bones and allow for a wide range of movements. As people grow older, they begin to lose skeletal muscle mass.

Because age-related skeletal muscle loss is often seen in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia, this study aimed to examine whether temporalis muscle loss (a measure of skeletal muscle loss) is associated with an increased risk of AD dementia in older adults.

The temporalis muscle is located in the head and is used for moving the lower jaw. Studies have shown that temporalis muscle thickness and area can be an indicator of muscle loss throughout the body.

“Measuring temporalis muscle size as a potential indicator for generalized skeletal muscle status offers an opportunity for skeletal muscle quantification without additional cost or burden in older adults who already have brain MRIs for any neurological condition, such as mild dementia,” said the study’s lead author, Kamyar Moradi, MD, postdoctoral research fellow in the Russell H. Morgan Department of Radiology and Radiological Sciences at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. “This is the first longitudinal study to demonstrate that skeletal muscle loss may contribute to the development of dementia.”

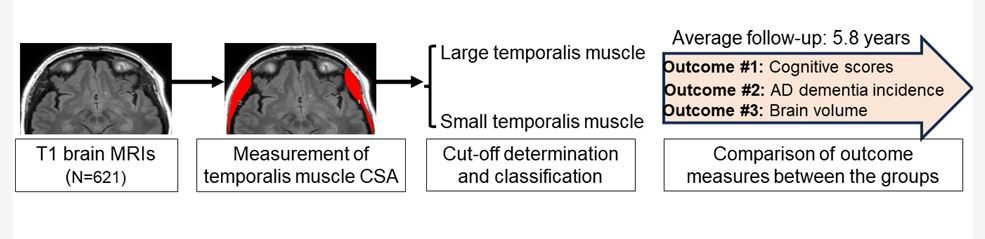

For the multidisciplinary research study, a collaboration between the radiology and neurology departments at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Dr Moradi and colleagues used baseline brain MRI exams from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative cohort to quantify skeletal muscle loss in 621 participants without dementia (mean age 77 years).

The researchers manually segmented the bilateral temporalis muscle on MRI images and calculated the sum cross-sectional area (CSA) of these muscles. Participants were categorized into two distinct groups: large CSA (131 participants) and small CSA (488 participants). Outcomes included subsequent AD dementia incidence, change in cognitive and functional scores, and brain volume changes between the groups. Median follow-up was 5.8 years.

Based on their analysis, a smaller temporalis CSA was associated with a higher incidence risk of AD dementia. Furthermore, a smaller temporalis CSA was associated with a greater decrease in memory composite score, functional activity questionnaire score and structural brain volumes over the follow-up period.

“We found that older adults with smaller skeletal muscles are about 60% more likely to develop dementia when adjusted for other known risk factors,” said the study’s co-senior author and professor of neurology, Marilyn Albert, PhD.

According to Shadpour Demehri, MD, co-senior author and professor of radiology, the study demonstrates that this muscle change can be opportunistically analyzed through any conventional brain MRI, even when conducted for other purposes, without incurring additional costs or burdens.

Dr Albert pointed out that early detection through readily available brain MRI could enable timely interventions to address skeletal muscle loss, such as physical activity, resistance training and nutritional support.

“These interventions may help prevent or slow down muscle loss and subsequently reduce the risk of cognitive decline and dementia,” Dr Demehri said.

Related Articles

Citation

. Muscle Loss May Increase Dementia Risk. Appl Radiol.

December 3, 2024