MRI Technique May Predict Impaired Fetal Growth

Images

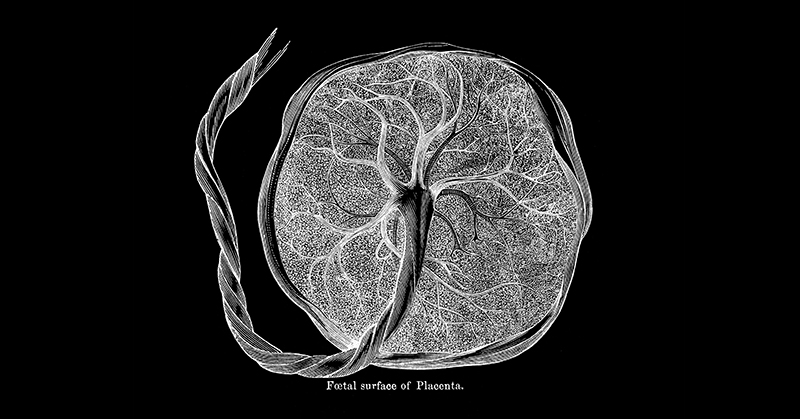

A National Institute of Health funded study reports that a MRI technique administered as early as the 14th week of pregnancy may predict the chances of impaired fetal growth. The technique measures the ability of the placenta to supply blood to the fetus. It appears to allow earlier diagnosis than the standard technique, ultrasound of the placenta, which can diagnose reductions in maternal blood flow to the placenta at 20 to 24 weeks. Earlier detection of fetal growth restriction and those at risk for being small for their gestational age at birth may lead to strategies for treating these conditions. The study, published in Placenta, was conducted by Sherin U Devaskar, MD, and colleagues at the University of California at Los Angeles.

Intrauterine growth restriction refers to poor growth of the fetus in the uterus. Small for gestational age means that a fetus or an infant is smaller or less developed than normal for the baby's sex and gestational age. Early in pregnancy, arteries in the wall of the uterus widen, supplying maternal blood to the fetus. Failure of the arteries in the wall of the uterus to widen sufficiently is thought to be one of the potential causes of intrauterine growth restriction and being born small for gestational age. Failure of the arteries to widen sufficiently deprives the fetus of the nutrients and oxygen it needs to grow. This failure also may lead to preeclampsia, a potentially life threatening complication of pregnancy resulting in high blood pressure and protein in the urine.

For the current study, researchers considered any of these three conditions in a pregnancy to be an indication of ischemic placental disease—an insufficient supply of maternal blood to the fetus.

Study participants underwent MRI scans of the placenta at 14 to 16 weeks of gestation and at 19 to 24 weeks. At each scan, measures were taken of the total placental volume, the degree of perfusion (maternal blood the placenta contained), and the placental blood’s oxygen content.

A total of 181 participants completed the study. Of these, 30 had ischemic placental disease and 151 did not. Those with ischemic placental disease were more likely to have smaller placental volume, perfusion, and oxygen content than those who did not.

Among those with ischemic placental disease, 17 had preeclampsia (3 with fetuses with intrauterine growth restriction that later were born small for gestational age). Among those with preeclampsia, 2 developed preeclampsia before 34 weeks and the remainder developed it after 34 weeks. A total of 11 had intrauterine growth restriction and 5 had newborns who were small for gestational age alone.

Compared to placentas of participants without ischemic placental disease, placentas of participants with growth restricted fetuses and small for gestational age infants had the greatest differences in placental volume, perfusion, and oxygen content. Of the placentas from pregnancies that later developed preeclampsia, only those with preeclampsia before 34 weeks differed significantly from those of participants without preeclampsia. Cases with early preeclampsia also had intrauterine growth restriction and small for gestational age births. The authors theorized that preeclampsia before 34 weeks may be a different, and more severe, form of the disease than preeclampsia that develops later.

The authors noted their results predicted intrauterine growth restriction and small for gestational age births from insufficient widening of the uterine arteries at 14 to 16 weeks—much earlier than previous studies. The authors called for a larger study to verify their results. If the results can be confirmed, the method could be used to identify pregnancies at risk for intrauterine growth restriction and small for gestational age births early, so that at-risk pregnancies could be diagnosed earlier and monitored more intensely for signs of problems. Similarly, earlier identification of these conditions could foster studies of earlier intervention and treatment.