MDCT of the central airways: Anatomy and pathology

Images

A variety of neoplastic, inflammatory and congenital diseases may affect the trachea and mainstem bronchi. The clinical manifestations of these diseases are frequently protean, including symptoms such as cough, hemoptysis, dyspnea and wheezing. Often, patients with these diseases are misdiagnosed with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

The central airways can be evaluated with computed tomography (CT), which can detect widening or narrowing of the airway, airway wall thickening, the location of an abnormality to guide interventions, and associated findings in the mediastinum or lung parenchyma. CT is inferior to bronchoscopy in evaluating mucosal abnormalities and may underestimate disease extent.

In this article, we review the anatomy of the central airways and describe different pathologic conditions. We group central-airway abnormalities by diffuse or focal tracheal wall thickening and morphologic abnormalities.Central airway anatomy

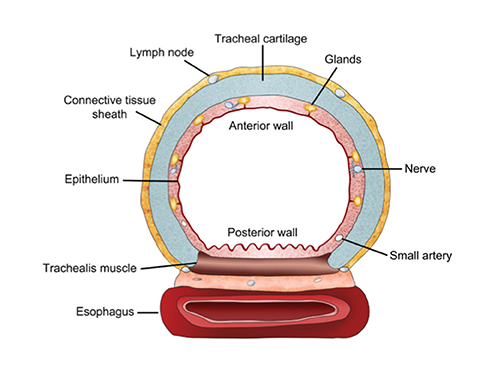

The trachea consists of 4 layers: an inner mucosal layer, a submucosal layer, cartilage and muscle, and an outer adventitial layer (Figure 1). The anterior trachea is composed of 16 to 22 C-shaped, cartilaginous rings linked by annular ligaments of fibroconnective tissue (Figure 2).1 The function of the rings is to support the trachea during expiration. The posterior tracheal wall lacks cartilaginous support, which is provided only by the thin band of the trachealis muscle. The posterior aspect of the trachea is also known as the membranous portion.

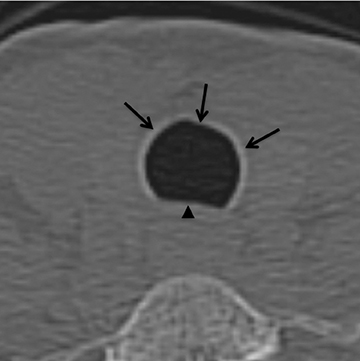

The trachea is approximately 10-12 cm in craniocaudal length, extending from the inferior aspect of the cricoid cartilage to the carina. The normal coronal diameter is 13-25 mm in men and 10-21 mm in women. The normal sagittal diameter is 13-27 mm in men and 10-23 mm in women.2 On CT, the normal tracheal wall is 1-3 mm thick, delineated by luminal air and the mediastinal fat or lungs. Calcification of the cartilage can be associated with senescent changes, particularly in older women.3

The superior aspect of the manubrium separates the extrathoracic and intrathoracic portions of the trachea.4 During expiration, CT images will demonstrate physiologic anterior bowing of the posterior non-cartilaginous aspect of the intrathoracic trachea with little change in contour of the anterolateral tracheal wall (Figure 3).

The mainstem bronchi are histologically similar, but have different morphologic features. The right mainstem bronchus courses posteriorly and superiorly to the right pulmonary artery (epaterial), while the left mainstem bronchus courses laterally and inferiorly in relation tothe left pulmonary artery (hyparterial). The right mainstem bronchus is shorter, has a more vertical course and originates more superiorly than the left.

Diffuse wall thickening sparing the posterior wall

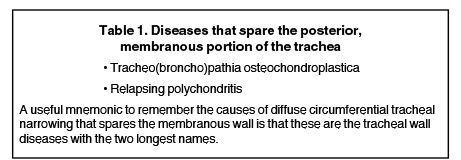

There are two main differentials to consider when there is diffuse tracheal wall thickening sparing the membranous wall (Table 1).

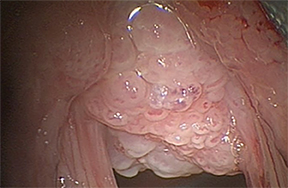

Tracheo(broncho)pathia osteochondroplastica

Tracheo(broncho)pathia osteochondroplastica (TPO) is histologically characterized by the development of nodules containing osseous orcartilaginous material in the submucosa of the lower trachea, with or without mainstem bronchi involvement. This is usually an incidental finding on chest CT performed for other reasons and most commonly seen in middle-aged men. These patients are commonly asymptomatic but sometimes may present with hemoptysis, dyspnea, stridor or hoarseness.

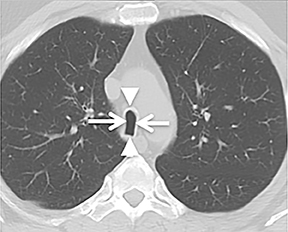

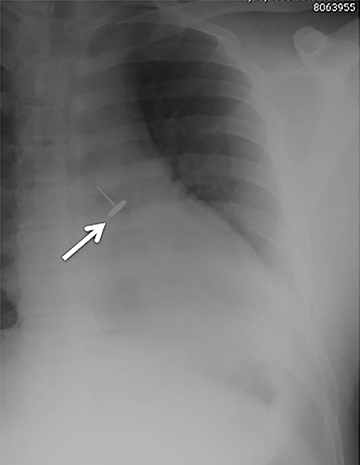

On CT, TPO appears as 1- to 3-mm calcified nodules arising from the cartilaginous, anterior ring of the trachea. These calcified, nodular excrescences protrude into the lumen of the airway, resulting in narrowing. The posterior wall of the trachea and mainstem bronchiare characteristically spared (Figure 4), which helps distinguish this from other disease processes.

Relapsing polychondritis

Relapsing polychondritis (RPC) is a rare autoimmune disorder that results in inflammation and destruction of cartilaginous structures throughout the body, including the ears, nose, joints and laryngotracheobronchial tree. The airway is involved in approximately 50% of patients.2

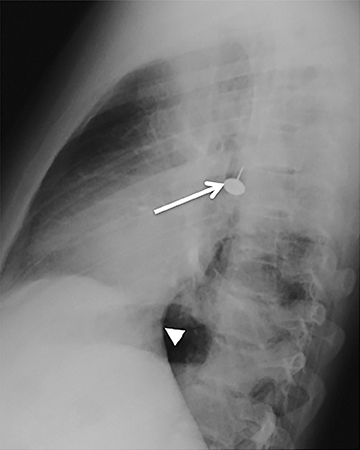

On CT, RPC is characterized by thickening of the anterior and lateral tracheal walls. In addition, the thickened walls demonstrate increased attenuation (Figure 5). There is often associated destruction of the cartilaginous tracheobronchial rings with sparing of the non-cartilaginous posterior wall.5 Tracheomalacia and/or large airway stenosis may develop as sequelae.2

Diffuse wall thickening with circumferential involvement

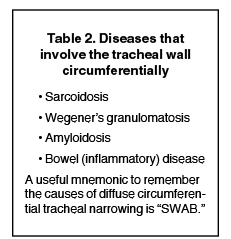

Diseases that cause diffuse circumferential wall thickening can generally be remembered as diseases associated with chronic inflammation (Table 2).

Wegener’s granulomatosis

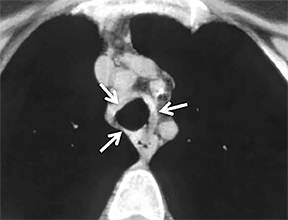

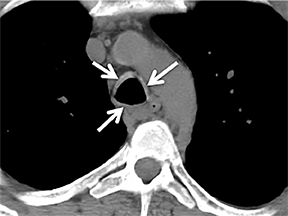

Wegener’s granulomatosis is an idiopathic disease characterized by a multisystemic necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis. There is no particular age predilection. The upper airways are nearly always affected, and the lungs and kidneys are involved in 90% and 80% of patients, respectively.6 Patients may present with respiratory signs and symptoms, and frequently patients have elevated serum c-antineutrophil antibodies against protease 3 in cytoplasmic granules (c-ANCA).7

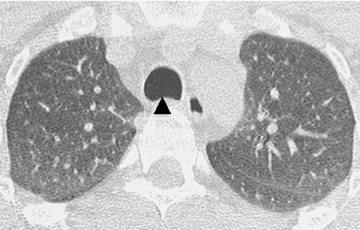

Diffuse circumferential tracheal and bronchial wall thickening may be present on CT (Figure 6). Approximately 25% of patients have subglottic stenosis and approximately 10% will have bronchial stenosis.8 Additional pulmonary findings on CT include pulmonary nodules and masses, some of which may be cavitary, consolidation and ground-glass opacities.2

Amyloidosis

Amyloidosis is a rare disorder of unknown etiology characterized by deposition of abnormal proteinaceous material in extracellular tissues and various organs throughout the body. The organs most commonly affected are the kidneys, liver, spleen, central nervous system andgastrointestinal tract. It may be idiopathic or associated with a variety of inflammatory, hereditary or neoplastic etiologies.9 Involvement of the tracheobronchial tree, although rare, is the most common manifestation of thoracic amyloidosis.2

Diffuse nodular thickening of the trachea and mainstem bronchi can be seen on thoracic CT. The subglottic trachea is involved most frequently. The nodular areas will commonly calcify; consequently, tracheobronchial amyloidosis may resemble TBO. However, in tracheobronchial amyloidosis there is circumferential wall involvement whereas in TBO, the posterior wall is spared. Bronchial occlusion and/orstenosis are known sequelae.9

Inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease-associated tracheobronchial involvement is uncommon; but when it does occur, it is seen late in the course of disease.2 This diagnosis should be considered in patients with a history of inflammatory bowel disease and asthma-like symptoms. CT may demonstrate focal or diffuse circumferential airway narrowing with either smooth or irregular wall thickening (Figure 7). Given its nonspecific imaging appearance, patient history is key to suggesting this diagnosis. Additional pulmonary findings include bronchiectasis, chronic bronchitis, obliterative bronchiolitis, and pulmonary fibrosis, with the latter two usually occurring as the result of some of the toxic pulmonary drugs used to treat this disorder.10

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is an idiopathic, multisystemic disorder characterized by formation of noncaseating hylinized granulomas. It typically involves the hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes and lung parenchyma, depending on which stage is present. Tracheobronchial involvement is rare, affecting up to 3% of patients and when present, most commonly involves the proximal trachea.9

CT may demonstrate extrinsic narrowing of the airways by adjacent lymph nodes. Alternatively, primary infiltration of the airway walls with noncaseating granulomas may occur.5 Additional pulmonary CT findings include multiple tiny lung nodules with a perilymphatic distribution(involving the fissural and pleural surfaces). Thickening and nodularity or the bronchovascular bundles or peribronchovascular consolidation can also be seen.2 Classically, parenchymal involvement is symmetrical and upper lobe predominance. Lymph node involvement is most commonly seen and tends to result in bulky, symmetrical bilateral hilar and mediastinal adenopathy which may or may not contain calcification.

Diseases with focal wall thickening

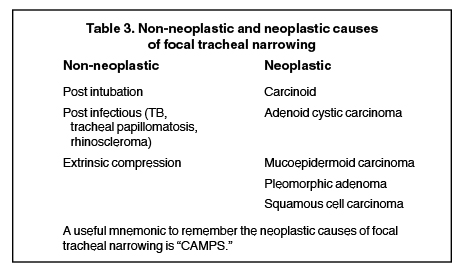

Myriad underlying conditions, including neoplasm, infection and trauma, can cause short-segment narrowing of the trachea, (Table 3).Many of these entities can be accurately characterized on cross sectional imaging.11

Non-neoplastic causes of tracheal stenosis

Iatrogenic tracheal injury is a well-recognized complication of endotracheal intubation and tracheostomy.12 The most common site of stricture is at the level of the inflated cuff (upper thoracic trachea, usually around the second or third thoracic vertebral level). The stricture occurs when cuff pressures exceed capillary arterial pressure, causing ischemia of the adjacent mucosa and leading to fibrotic narrowing, usually within 3 to 6 weeks after removal.13,14 Risk factors include prolonged intubation as well as certain intrinsic patient characteristics such as female sex, smoking status and a history of diabetes mellitus.15 Use of low-pressure high-volume (LPHV) cuffs appears to decrease the odds of occurrence.15,16

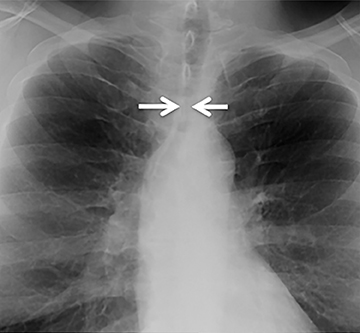

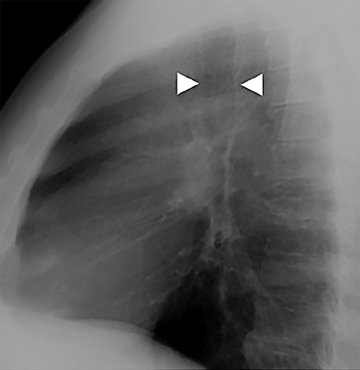

CT demonstrates circumferential subglottic tracheal wall thickening causing short segment narrowing in the region of the cuff site, usually 3 to 6 cm above the carina (Figure 8). Chest radiographic findings may be subtle, but when visible, narrowing of the airway in a characteristic location may be identified. In post-tracheostomy patients, the narrowing is most often located at the prior stoma site; however, the cuff site is commonly affected in this patient population as well.17

Tracheal papillomatosis

Tracheal papillomatosis is an airway manifestation of human papilloma virus (HPV), which is thought to be contracted via vertical transmission from an infected mother. The gold standard for diagnosis is flexible bronchoscopy; however, because patients present with nonspecific symptoms ranging from cough to complete airway obstruction, imaging is often obtained as part of the initial workup.18

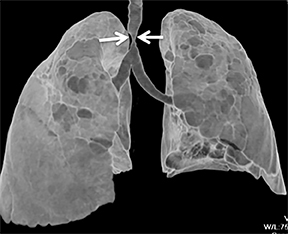

The CT appearance of papillomatosis shows multiple intraluminal nodules of varying size and number, without sparing of the membranous trachea (Figure 9). The disease can extend into the distal airways, and is occasionally associated with recurrent airspace consolidation,atelectasis, hemorrhage and parenchymal cystic lesions or cavitary lung nodules.17,19 Transformation to squamous cell carcinoma is a rare but well-documented occurrence.20

Post-infectious stenosis

Infectious involvement of the large airways occurs not infrequently; however, long-term sequelae are rarely seen. The most common infection described to result in airway abnormalities is Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It is reported that approximately 10-40% of all tuberculosis patients exhibit evidence of endobronchial infection.9 Post-infectious strictures are seldom restricted to the trachea alone, but rather, are multifocal throughout the central airways.21 Tracheal stenosis in the setting of tuberculosis infection can occur both during active disease, when the affected regions appear thick walled and irregular and after treatment, when the stenotic areas have become thin-walled and fibrotic. It is important to be aware that concurrent intrapulmonary manifestations of tuberculosis may not be evident on imaging at the time of diagnosis.

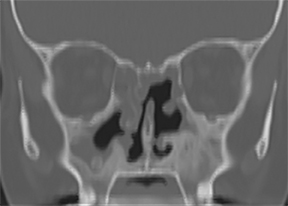

Rhinoscleroma is a chronic granulomatous infection due to Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis, which affects the respiratory epithelium from the nose to the bronchi. Laryngeal involvement has been reported to occur in 15-80% of cases.22

The paranasal sinuses and pharynx are also commonly affected. This infection is rare in the United States but endemic in Central America, Africa, Egypt, India and Indonesia. Imaging findings include focal narrowing of the trachea or bronchi with rarely associated calcification.9 Rhinoscleroma may demonstrate nodular deformity of the tracheal mucosa or severe, circumferential thickening of the walls of the trachea and central bronchi resulting in marked luminal narrowing (Figure 10).

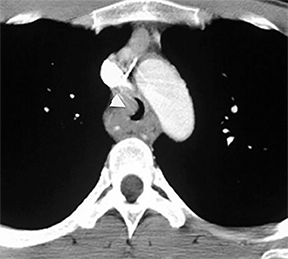

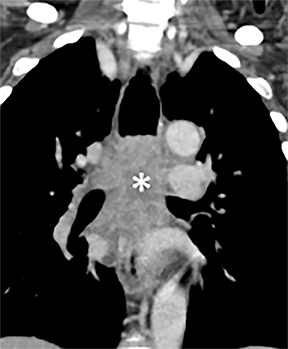

Extrinsic compression

Narrowing of the airway secondary to extrinsic compression can present with respiratory compromise, asthma-like symptoms and occasionally hemoptysis.

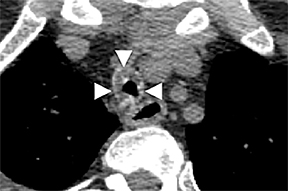

Compression frequently occurs due to mediastinal masses (Figure 11), with thyroid goiter being one of the most commonly encountered etiologies, and vascular abnormalities.23 However, unusual causes, such as osteophytosis of the cervical spine (Forestier-Rotes-Querol’s disease, also known as diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis) have been reported.24 Sometimes radiographic imaging of the chest is normal or nonspecific, and cross-sectional imaging is usually required to make or confirm the diagnosis.

Malignant causes of tracheal stenosis

The most common malignant cause of tracheal narrowing is an adjacent neoplastic process that directly invades the trachea (such as lungor esophageal cancer). Primary tracheal neoplasms are rare and are more commonly malignant than benign (Table 3). Of the malignant neoplasms, the most common are squamous cell carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, carcinoid and mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Less commonly, benign neoplastic entities, such as pleomorphic adenoma, can affect the central airways. It is important to stress that imaging findings of tracheal neoplasms are nonspecific and cannot reliably distinguish between the different histologic types.

Squamous cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common of the primary tracheal neoplasms, comprising approximately one-third. As is true ofSCC in other head and neck locations, tracheal SCC is seen in patients in their 6th and 7th decade with a significant smoking history.

On CT, the mass can be focal or circumferential. The focal appearance is that of an intraluminal soft tissue mass with smooth, lobulated or irregular contour. Direct mediastinal extension of tumor is not uncommon (Figure 12). Approximately 10% of lesions are multifocal, which necessitates careful evaluation of the remainder of the airway when SCC is suspected.25

Adenoid cystic carcinoma

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) is a well-differentiated, slow growing tumor that typically affects the salivary glands; however, on occasion, the trachea is the primary site. ACC is also one of the more common tracheal neoplasms, with prevalence similar to that of squamous cell carcinoma, comprising approximately one-third of all primary tracheal neoplasms.26 It affects men and women equally and often presents in the 5th or 6th decade. Unlike tracheal squamous cell carcinoma, ACC occurs more commonly in non-smokers and younger patients.26

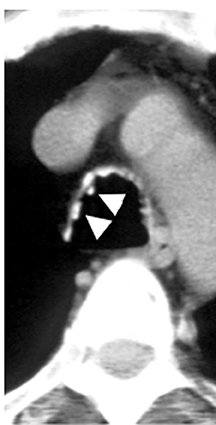

The typical CT finding is a soft tissue mass, commonly located in the proximal half of the trachea, and more frequently along the posterolateral wall, although other sites are also possible (Figure 13). The tumor typically demonstrates extensive submucosal and transmural spread; however, distant metastases do not usually occur until late in the disease course.26

Carcinoid

Carcinoid tumors are neoplasms of neuroendocrine origin that rarely affect the respiratory tree. When they do, they are most often located in the main, lobar, or segmental airways; however, the trachea can also be affected. Patients are usually in their third to fifth decade and can present with airway obstruction resulting in atelectasis or recurrent postobstructive pneumonia in the same lobe. Because the majority of these tumors arise in or close to the central airways, patients commonly present with symptoms related to airway involvement, such as asthma, cough or hemoptysis. Symptoms related to ectopic hormone production (carcinoid syndrome) are rare with pulmonary carcinoids.27 These tumors usually do not have any association with cigarette smoking.

There are two histologic subtypes of bronchial carcinoid. Typical carcinoids comprise up to 90% of cases. They are generally small, do not metastasize to regional lymph nodes, and are associated with an excellent prognosis, with surgical resection resulting in a cure in most cases. These tumors are classically slow growing, with a doubling time usually greater than two years. Carcinoids are also known to give a false-negative result on PET scan due to their low metabolic activity. Atypical carcinoids are generally larger, metastasize to regional lymph nodes and are associated with a worse prognosis.28

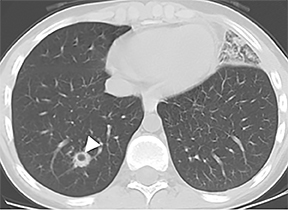

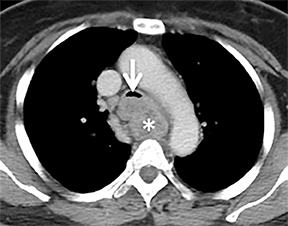

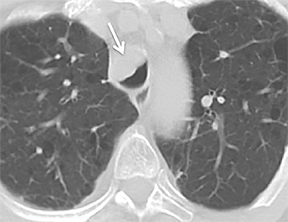

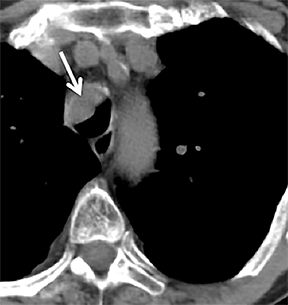

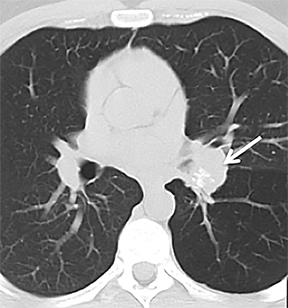

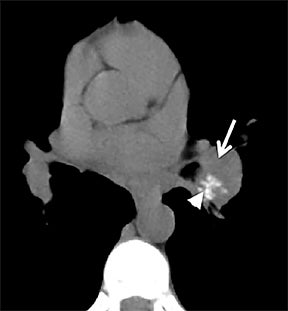

On cross-sectional imaging, carcinoid tumors classically appear as a centrally located, endobronchial lesions. A smaller percentage of tumors present as a peripheral, well-circumscribed, solitary pulmonary nodule. They are usually of homogeneous soft-tissue density. If intravenous contrast is administered, they can demonstrate avid enhancement. Internal calcifications may be present in up to approximately one-third of cases (Figure 14).28 Lesions can extend beyond the airway wall, with the bulk of the lesion extraluminal in location (known as the “tip of the iceberg sign” appearance at bronchoscopy).29

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma comprises approximately 0.1-0.2% of all pulmonary neoplasms, and like adenoid cystic carcinoma and pleomorphic adenoma, arises from minor salivary gland tissue, most often in the central airways.29 Presentation is variable, ranging from asymptomatic, to cough, wheezing, and/or hemoptysis, usually in a young patient.

Similar to its clinical presentation, the CT appearance of mucoepidermoid carcinoma is quite variable. The tumor often appears as an enhancing lesion with smooth or lobulated contours, with or without punctate internal calcifications. Cavitary lesions, as well as diffuse tracheal wall thickening, have also been described.29,30

Pleomorphic adenoma

While pleomorphic adenoma is the most common neoplasm of the major salivary glands, it rarely affects the trachea. As with pleomorphic adenomas of other locations, lesions within the airway have been noted to have a variable appearance, and few have been described.31 As with other tracheal tumors, distinguishing these from the other histologic types based solely on imaging appearance is impossible.

Morphologic abnormalities of the central airways

There are a variety of acquired and morphologic central airway abnormalities. Congenital abnormalities may occur anywhere along the tracheobronchial tree; however, the anomalies are most common in the upper lobe bronchi.32 Awareness of these variants can be very helpful in guiding the pulmonologist during bronchoscopy.

Congenital bronchial variant

While there are congenital variations in bronchial branching patterns, the main ones that arise from central bronchi include tracheal bronchus and accessory cardiac bronchus. These are usually incidental findings at CT, although less commonly they may be associated with recurrent infection. A tracheal bronchus is a broad term that includes bronchial anomalies that originate from the trachea or a main bronchus.A prevalence of up to 2% for right tracheal bronchus (with the apical segment of the right upper lobe arising from the distal trachea as th emost common) and up to 1% for left tracheal bronchus has been reported.32 The bronchus may be termed supernumerary or displaced, depending on whether they coexist with a normal type of branching pattern of the upper lobe bronchus or if they replace the normal upper lobe bronchus, respectively. The displaced type is more common than the supernumerary type.32 When the entire right upper lobe bronchus is displaced to the trachea, this has been termed “pig bronchus” and has a frequency of 0.2% (Figure 15).32

An accessory cardiac bronchus occurs in 0.08% of the population and is defined as a supernumerary bronchus arising from the inner wall of the right main bronchus or bronchus intermedius opposite to the origin of the right upper lobe bronchus.32 This bronchus is typically blind-ending and usually does not cause any symptoms.

Tracheomalacia

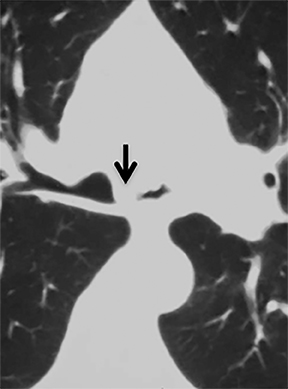

Tracheomalacia results from weakness of the cartilaginous support of the tracheobronchial walls as well as from hypotonia of the myoelastic elements. The most common etiology is COPD. Other etiologies include long-term intubation, tracheal trauma, congenital abnormalities,chronic extrinsic compression in the setting of a vascular ring or sling, chronic inflammation, infection or may be idiopathic.1 On imaging, tracheomalacia is characterized by greater than 50% collapse of the intrathoracic trachea during forced expiration.1 With this disease process, the posterior trachea bows anteriorly during expiration, resulting in the appearance of a frown, the so-called “frown” sign (Figure 16).33

Tracheobronchomegaly

Tracheobronchomegaly (Mounier-Kuhn syndrome) is characterized by diffuse airway dilatation, which makes it unique from the other morphologic abnormalities of the central airways. Its etiology may be either congenital or acquired atrophy of the connective tissue of the trachea and central bronchi. Tracheal diameter greater than 3 cm or mainstem bronchi diameters greater than 2.4 cm are highly suggestive of the disease.3 Additionally, prominent airway diverticula may project through the cartilaginous rings, resulting in a corrugated appearance of the central airways.2 The abnormal trachea often demonstrates evidence of tracheomalacia; i.e., it tends to collapse with forced expiration.

Saber-sheath trachea

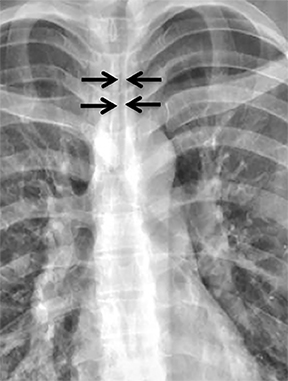

Saber-sheath trachea is a common acquired morphologic abnormality of the intrathoracic trachea, occurring frequently in men with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.1 Only the intrathoracic trachea is involved with the extrathoracic trachea remaining unaffected.

On imaging, the intrathoracic trachea demonstrates an abnormally marked decrease in the transverse diameter with an associated increase in the AP diameter (Figure 17). There is no associated tracheal wall thickening. With a saber-sheath trachea, the ratio of the sagittal-to-coronal diameter of the trachea usually exceeds 2:1.1 Remember to look for other effects of smoking-related lung disease, such as emphysema, hyperinflation, air-trapping, smoking-related interstitial lung disease, and lung cancer.

Tracheal diverticulum

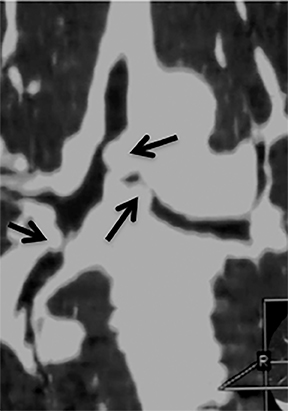

Tracheal diverticula may be congenital or acquired. Congenital diverticula are more common in men.34 Typically, the diverticulum occurs4-5 cm inferior to the vocal cords along the right lateral aspect of the trachea. It is thought to represent a vestigial supernumerary lung or a remnant of an abnormally high lung bud.35 Acquired tracheal diverticula may occur anywhere, but are most commonly seen at the posterolateral aspect of the trachea superiorly on the right at the level of the thoracic inlet, and they occur as a result of increased intraluminal pressure.34 Whether congenital or acquired, almost all cases of tracheal diverticula are asymptomatic.1 It is important to be aware of these and not to mistake them for pneumomediastinum or other pathology.

Foreign bodies

Central airway foreign bodies are the most common endobronchial “mass” encountered in children, but can also be seen in adult patients.They tend to lodge in the main or lobar bronchi, with the right mainstem bronchus being the most common location given its more vertical course.

Radiographically, the foreign body may be visually apparent if it is radiopaque (Figure 18). If the foreign body is radiolucent, then secondary findings of resultant airway obstruction, such as atelectasis or air-trapping, may be present.36

References

- Boiselle PM. Imaging of the large airways. Clin Chest Med. 2008;29:181-193.

- Chung JH, Kanne JP, Gilman MD. CT of diffuse tracheal diseases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:W240-246.

- Webb EM, Elicker BM, Webb WR. Using CT to diagnose nonneoplastic tracheal abnormalities: Appearance of the tracheal wall. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000; 174:1315-1321.

- Gamsu G, Webb WR. Computed tomography of the trachea: Normal and abnormal. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1982; 139:321-326.

- Kwong JS, Muller NL, Miller RR. Diseases of the trachea and main-stem bronchi: Correlation of CT with pathologic findings. Radiographics. 1992;12:645-657.

- Allen SD, Harvey CJ. Imaging of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Br J Radiol. 2007; 80:757-765.

- Pretorius ES, Stone JH, Hellman DB, et al. Wegener’s Granulomatosis: CT evolution of pulmonary parenchymal findings in treated disease. Crit Rev Comput Tomogr. 2004; 45:67-85.

- Lohrmann C, Uhl M, Kotter E, et al. Pulmonary manifestations of wegener granulomatosis: CT findings in 57 patients and a review of the literature. Eur J Radiol. 2005; 53:471-477.

- Prince JS, Duhamel DR, Levin DL, et al. Nonneoplastic lesions of the tracheobronchial wall: Radiologic findings with bronchoscopic correlation. Radiographics.2002; 22 Spec No:S215-230.

- Spira A, Grossman R, Balter M. Large airway disease associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Chest. 1998; 113:1723-1726.

- Koletsis EN, Kalogeropoulou C, Prodromaki E, et al. Tumoral and non-tumoral trachea stenoses: Evaluation with three-dimensional CT and virtual bronchoscopy. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007; 2:18.

- Cooper JD, Grillo HC. The evolution of tracheal injury due to ventilatory assistance through cuffed tubes: A pathologic study. Ann Surg. 1969; 169:334-348.

- Wain JC. Postintubation tracheal stenosis. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 2003; 13:231-246.

- Weymuller EA, Jr. Laryngeal injury from prolonged endotracheal intubation. The Laryngoscope. 1988; 98:1-15.

- Whited RE. Laryngeal dysfunction following prolonged intubation. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1979; 88:474-478.

- Zias N, Chroneou A, Tabba MK, et al. Post tracheostomy and post intubation tracheal stenosis: Report of 31 cases and review of the literature. BMC Pulm Med. 2008; 8:18.

- Kligerman S, Sharma A. Radiologic evaluation of the trachea. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009; 21:246-254.

- Harris K, Chalhoub M. Tracheal papillomatosis: What do we know so far? Chron Respir Dis. 2011; 8:233-235.

- Ingegnoli A, Corsi A, Verardo E, et al. Uncommon causes of tracheobronchial stenosis and wall thickening: MDCT imaging. Radiol Med. 2007; 112:1132-1141.

- Lam CW, Talbot AR, Yeh KT, et al. Human papillomavirus and squamous cell carcinoma in a solitary tracheal papilloma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004; 77:2201-2202.

- Choe KO, Jeong HJ, Sohn HY. Tuberculous bronchial stenosis: CT findings in 28 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990; 155:971-976.

- Soni NK. Scleroma of the larynx. J Laryngol Otol. 1997; 111:438-440.

- Constenla I, Alvarez B, Yugueros X, et al. Innominate artery aneurysm with hemoptysis and airway compression in a patient with bovine aortic arch. J Vasc Surg. 2012; 56:822-825.

- Karlins NL, Yagan R. Dyspnea and hoarseness. A complication of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis. Spine.1991; 16:235-237.

- Ferretti GR, Bithigoffer C, Righini CA, et al. Imaging of tumors of the trachea and central bronchi. Radiol Clin N Am.2009; 47:227-241.

- Kwak SH, Lee KS, Chung MJ, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the airways: Helical CT and histopathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:277-281.

- Tryfon S, Parisis V, Ioannis K, et al. Excessive muscle paralysis due to pulmonary carcinoid—a case report. Clin Med Insights Case Rep. 2012; 5:43-48.

- Marom EM, Goodman PC, McAdams HP. Focal abnormalities of the trachea and main bronchi. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001; 176:707-711.

- Fisher DA, Mond DJ, Fuchs A, et al. Mucoepidermoid tumor of the lung: CT appearance. Comput Med Imaging Graph.1995; 19:339-342.

- Li X, Zhang W, Wu X, et al. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the lung: Common findings and unusual appearances on CT. Clin Imaging. 2012; 36:8-13.

- Aribas OK, Kanat F, Avunduk MC. Pleomorphic adenoma of the trachea mimicking bronchial asthma: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2007; 37:493-495.

- Ghaye B, Szapiro D, Fanchamps JM, et al. Congenital bronchial abnormalities revisited. Radiographics.2001; 21:105-119.

- Boiselle PM, Ernst A. Tracheal morphology in patients with tracheomalacia: Prevalence of inspiratory lunate and expiratory “frown” shapes. J Thoracic Imaging. 2006; 21:190-196.

- Soto-Hurtado EJ, Penuela-Ruiz L, Rivera-Sanchez I, et al. Tracheal diverticulum: A review of the literature. Lung. 2006; 184:303-307.

- Frenkiel S, Assimes IK, Rosales JK. Congenital tracheal diverticulum. A case report. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1980; 89:406-408.

- Dähnert W. Radiology review manual, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams Wilkins, 2007.