Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis

Images

Case Summary

A teenager with a medical history of autoimmune pancreatitis who had been recently weaned off steroids, presented with epigastric pain, epistaxis, watery diarrhea, nonbloody emesis, weight loss, and hemoptysis. Physical exam was significant for decreased bibasilar breath sounds and epigastric tenderness. Pertinent laboratory findings included positive PR3-ANCA antibodies, elevated C-reactive protein and sedimentation rate, and microscopic hematuria.

Imaging Findings

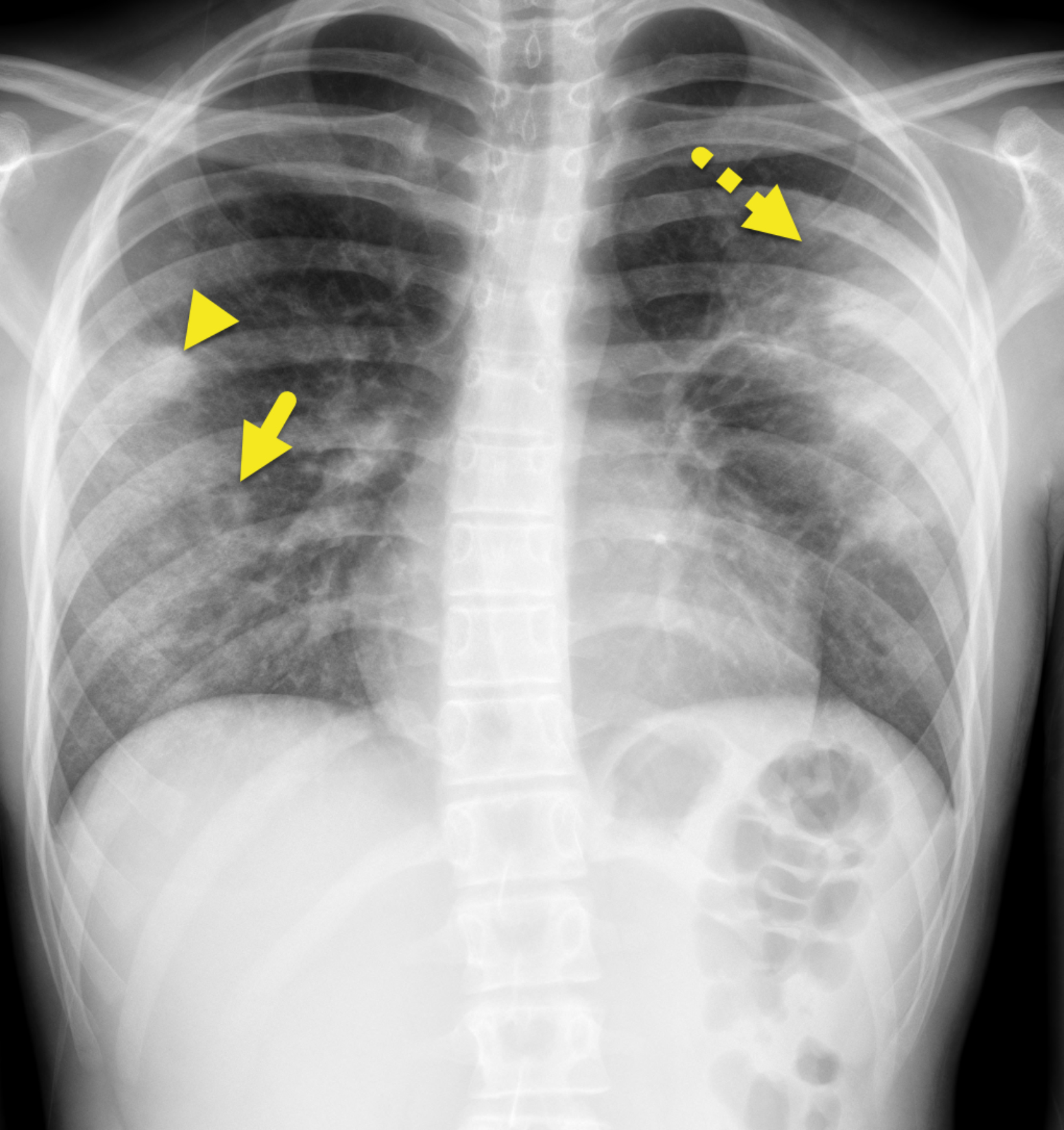

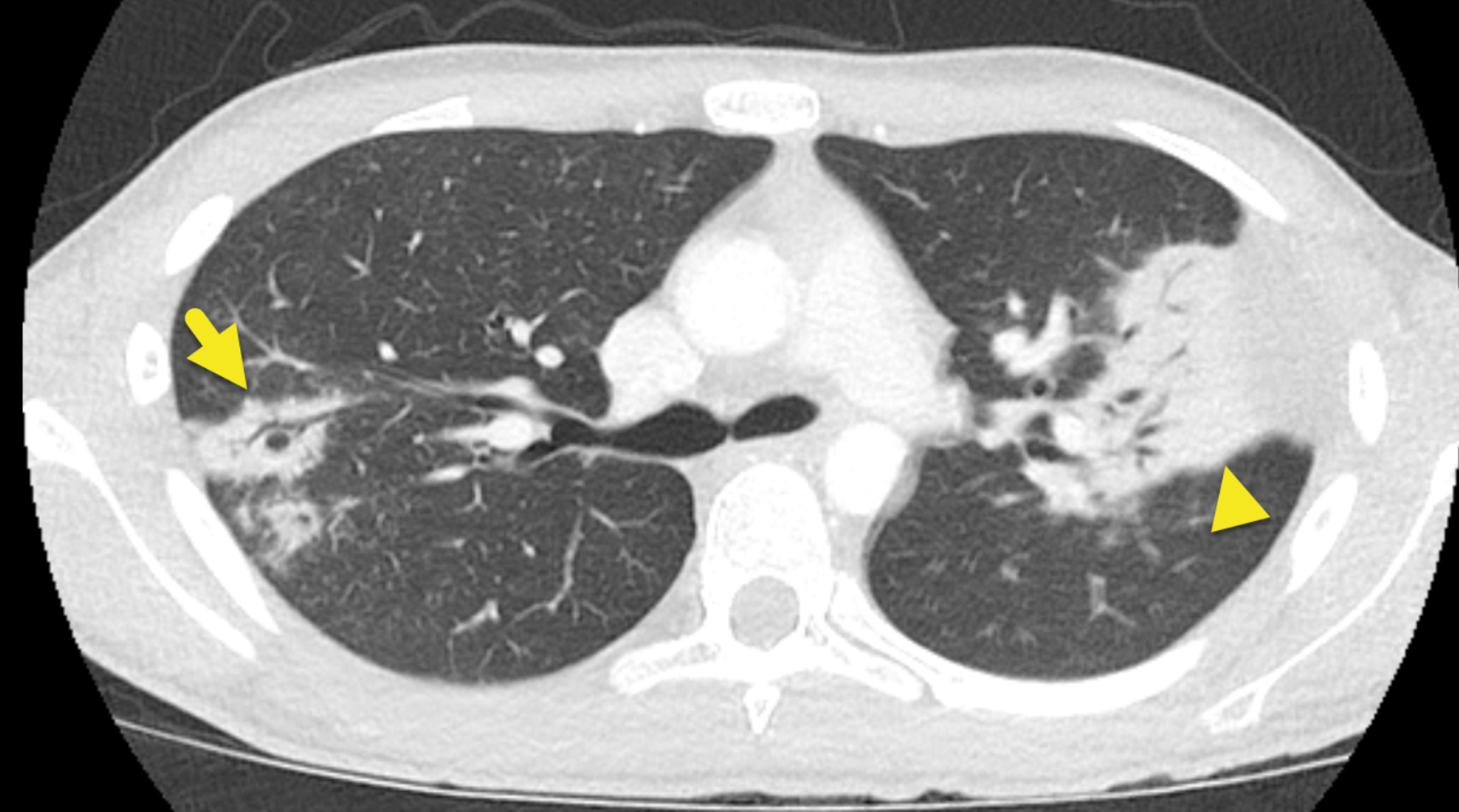

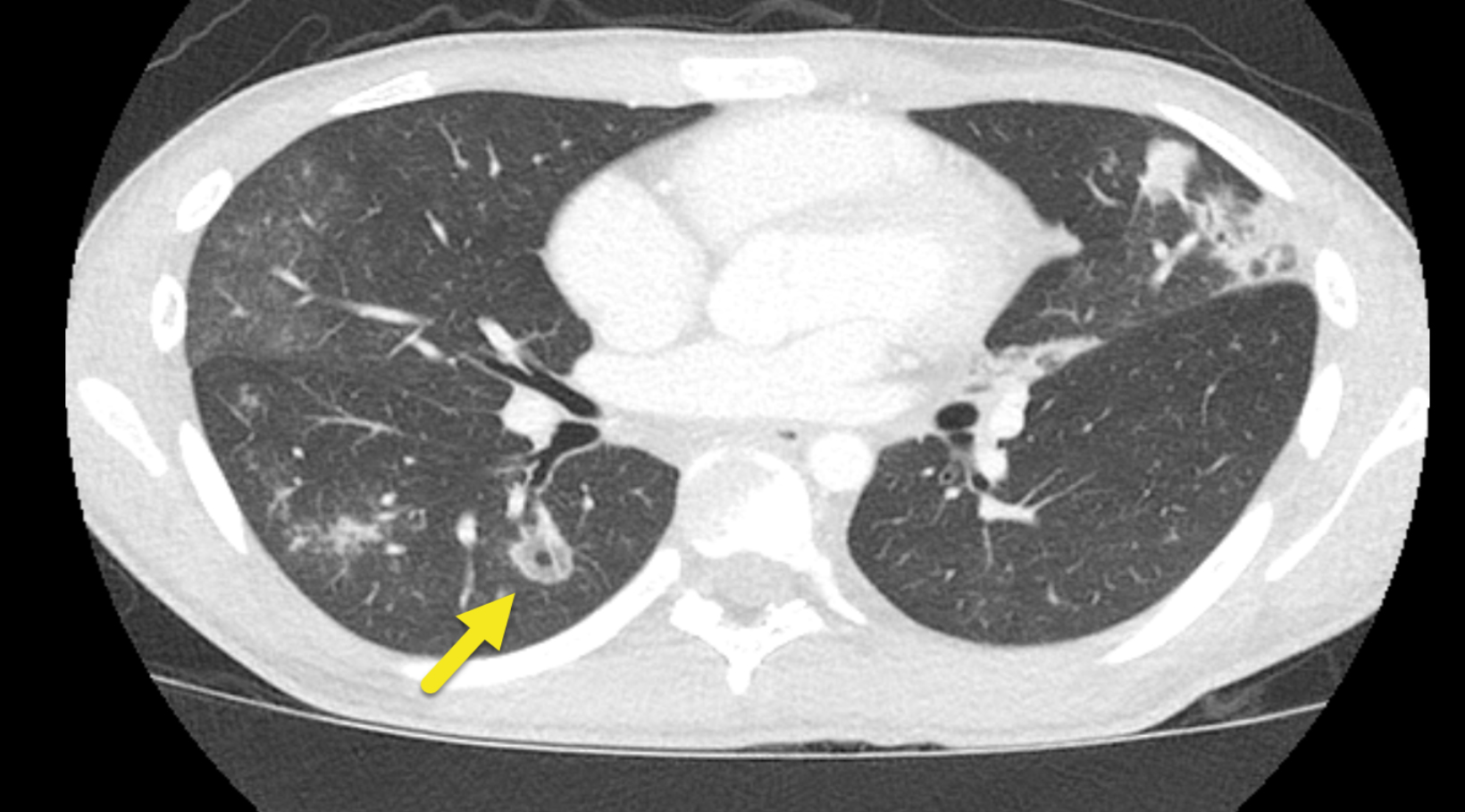

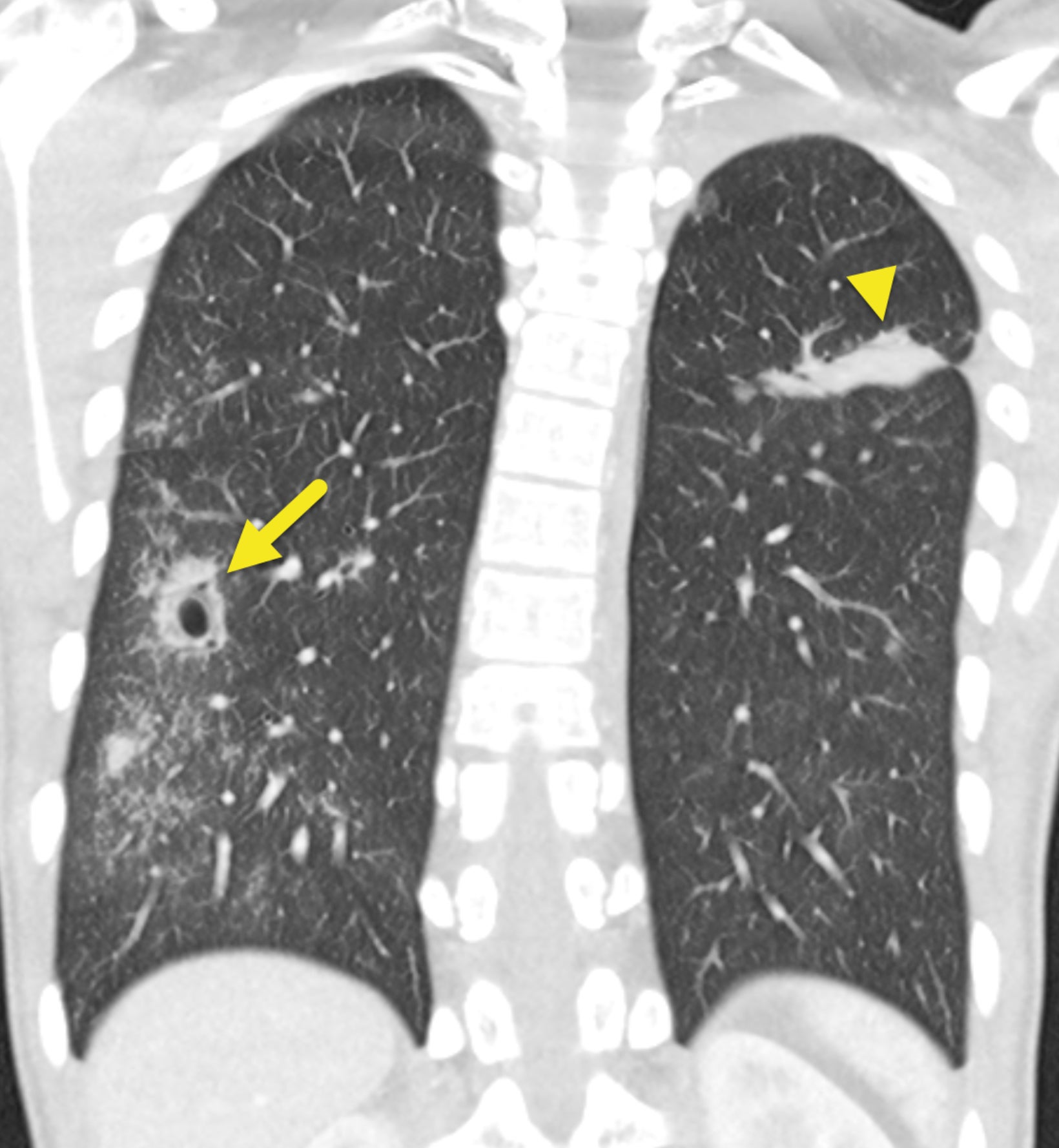

Chest radiograph (Figure 1) showed confluent and hazy opacities in both lungs. Solid and cavitary nodules were visible in the right lung. On chest computed tomography (Figure 2), the lungs were diffusely abnormal. There were multiple areas of consolidation, ground-glass opacity, and solid or cavitary pulmonary nodules. Areas of consolidation were associated with air bronchograms. The cavitary lesions had a thick wall with surrounding ground-glass opacity.

Diagnosis

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis).

The differential diagnosis of a child with chronic cough, hemoptysis, and multifocal pulmonary infiltrates is broad and includes infectious, vascular, and congenital/syndrome-related etiologies; lower respiratory infections, atypical infections, and fungal infections. The differential diagnosis also includes rare vascular etiologies such as lupus pneumonitis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis, IgA nephropathy, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, pulmonary artery rupture, and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. Potential congenital/syndrome-related etiologies include Goodpasture syndrome, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, and cystic fibrosis.1

Discussion

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is a rare multisystem, autoimmune disease of unknown etiology characterized by granulomatous, necrotizing lesions affecting small- to medium-sized blood vessels. It most commonly affects middle-aged women.

When pediatric patients are affected, clinical manifestations are predominantly in the pulmonary and renal systems.2 The eyes (scleritis), ears (hearing loss), skin (purpura), and musculoskeletal (myalgia) and nervous system (peripheral neuropathies) can also be involved. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for diagnosing GPA require two of the following: a) abnormal chest imaging; b) granulomatous inflammation shown on biopsy; c) oral ulcers or nasal discharge, and d) urinalysis with >5 RBC/ high-power field or red blood cell casts.3

GPA is more commonly diagnosed in adults than in children; prevalence in the pediatric population ranges from 0.45-6.39 cases/million/year depending on the referenced study.4

Panupattanapong, et al, reported the largest cohort of patients with GPA to date (n=5,562).5 In their study, 3.8% of all patients had pediatric-onset disease. Patients with pediatric-onset disease were slightly more likely to be female and had higher rates of hospi- talization, severe infections, and hematological complications when compared to patients with adult-onset disease.5 Most pediatric patients initially present with upper respiratory tract signs and symptoms, including epistaxis, nasal obstruction, and rhinosinusitis. Lower respiratory tract signs may also be present and include hemoptysis, pulmonary infiltrates, and pulmonary hemorrhage.

The radiographic findings of GPA are variable. Chest X-rays often show multiple nodules of variable sizes that can wax and wane over time. Cavitation can be appreciated in approximately 50% of cases. Initial radiographs may show consolidation or multifocal hazy opacities.6

Chest CT is recommended by the American College of Rheumatology. It may show multiple pulmonary nodules (2-4 cm), air space consolidation, ground glass opacities, tracheobronchial wall thickening, and mild bronchiectasis. Less common findings are pleural effusions and mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

Facial CT can identify sinonasal abnormalities (air-fluid levels, sinus mucosal thickening, or soft-tissue nodules) and orbital manifestations (proptosis and inflammation).7

The renal abnormalities of GPA are not readily appreciable on cross-sectional imaging. Rather, they are identified via renal biopsy, revealing crescentic glomerulonephritis with possible immune complexes. Image-guided percutaneous biopsy is well suited to this patient group.

There are no specific guidelines for the management of GPA in children. Thus, treatment is extrapolated from adult management and expert consensus. Corticosteroids with either cyclophosphamide or rituximab are the preferred regimen to induce remission of newly diagnosed disease.4 Patients have an excellent prognosis with a high likelihood of disease remission with therapy.

Conclusion

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, while more commonly identified in adults, should be suspected in children presenting with hemoptysis, hematuria, and chest imaging showing cavitary pulmonary nodules, ground-glass opacity, and consolidation.

References

Citation

AJ NDTRSCLYT.Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis. Supplement to Applied Radiology. 2022; (5):11-13.

September 2, 2022