Global Health Care Inequalities of Head and Neck Cancer Imaging and Treatment Protocols Emphasizing PET/CT Availability

With more than 660,000 new cases and 325,000 deaths annually worldwide, head and neck cancer is the seventh most common cause of global cancer, with a disparate incidence and mortality between low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and high-income countries (HICs), the latter demonstrating higher incidence but lower mortality.1, 2

Moreover, there seems to be an increasing growth of the world cancer burden, with a steep-slope rate in LMICs compared with HICs.3 - 5 Positron emission tomography / computed tomography (PET/CT) imaging plays a crucial role in enabling the detection, staging, and restaging after treatment of head and neck cancers6 and is an essential tool for reducing morbidity and mortality.

However, there are significant discrepancies in availability, cost, and accessibility, particularly in the US compared with LMICs.7, 8 This, in turn, results in health care disparities that negatively impact health outcomes for the LMIC populations.9 While the primary driver of health care inequities in access to imaging for head and neck cancers is the number of scanners, such as PET/CT and MRI and the number of radiologists in LMICs, this article discusses other potential factors and strategies to address them.

Specific Health Care Disparities

PET/CT Scanners Per Capita

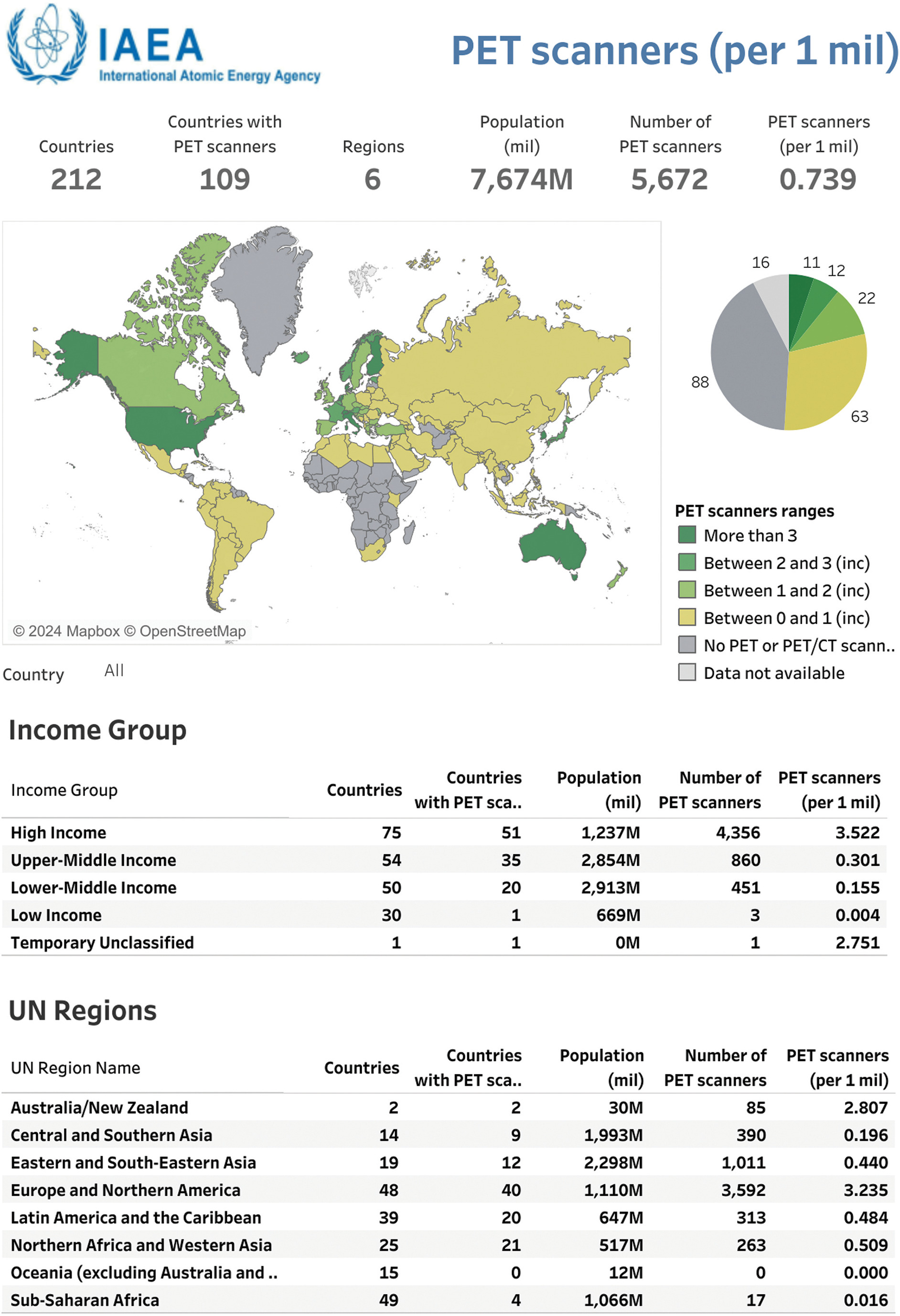

The US and other HICs boast a high number of PET/CT scanners compared with many other lower-income nations, owing to their extensive health care infrastructure and technological advancements, with an average of 3522 PET scanners per million people ( Figure 1 ).2 In contrast, many LMICs struggle with a scarcity of PET/CT scanners, with an average of 301 per million residents for upper-middle-income countries and none at all in most of Africa ( Figure 1 ).2 These shortages limit access to this important imaging technology for a significant portion of the LMIC population, delaying diagnosis and treatment and ultimately compromising patient outcome.2

PET scanners per 1 million residents. Data generated from IAEA IMAGINE.6

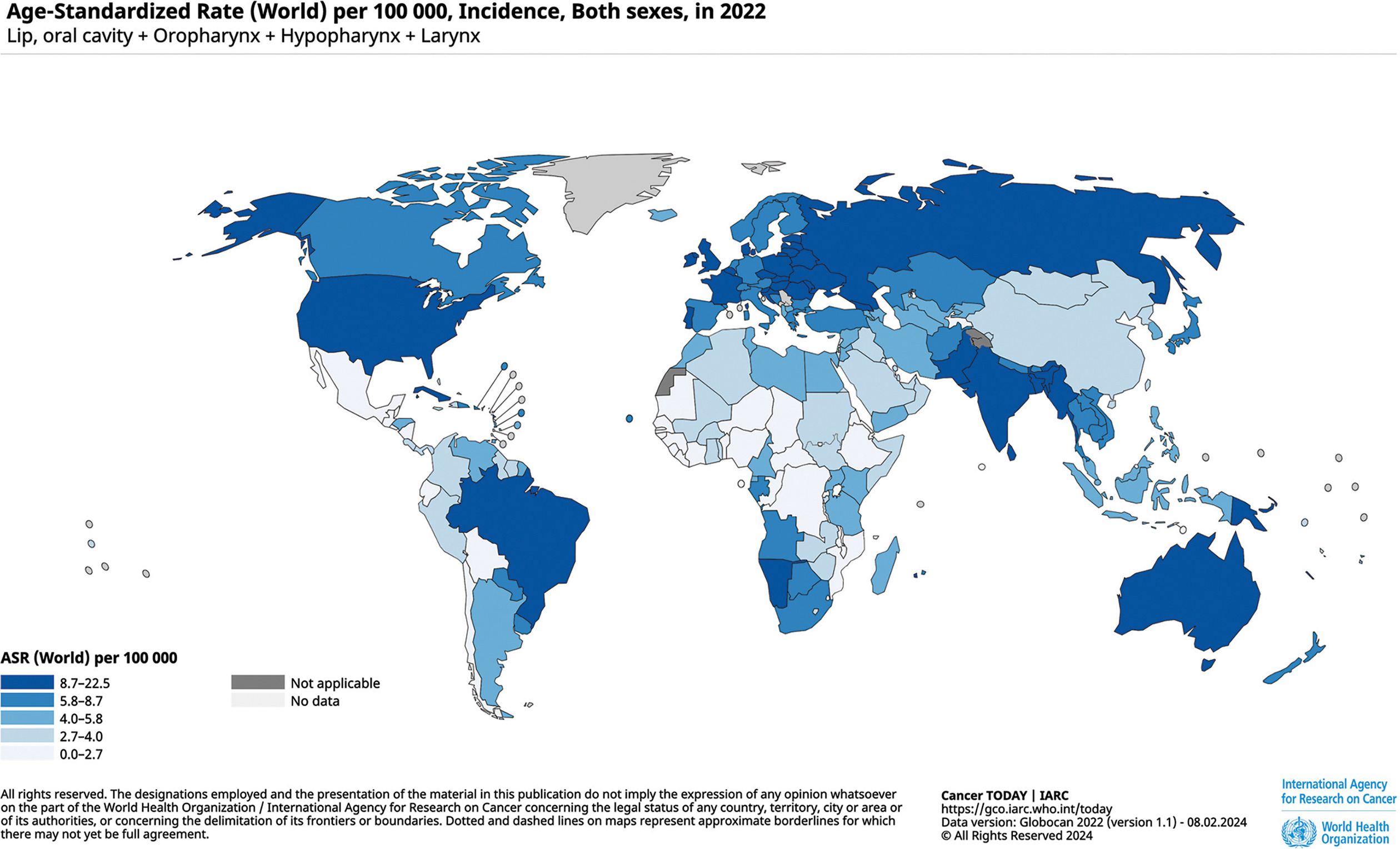

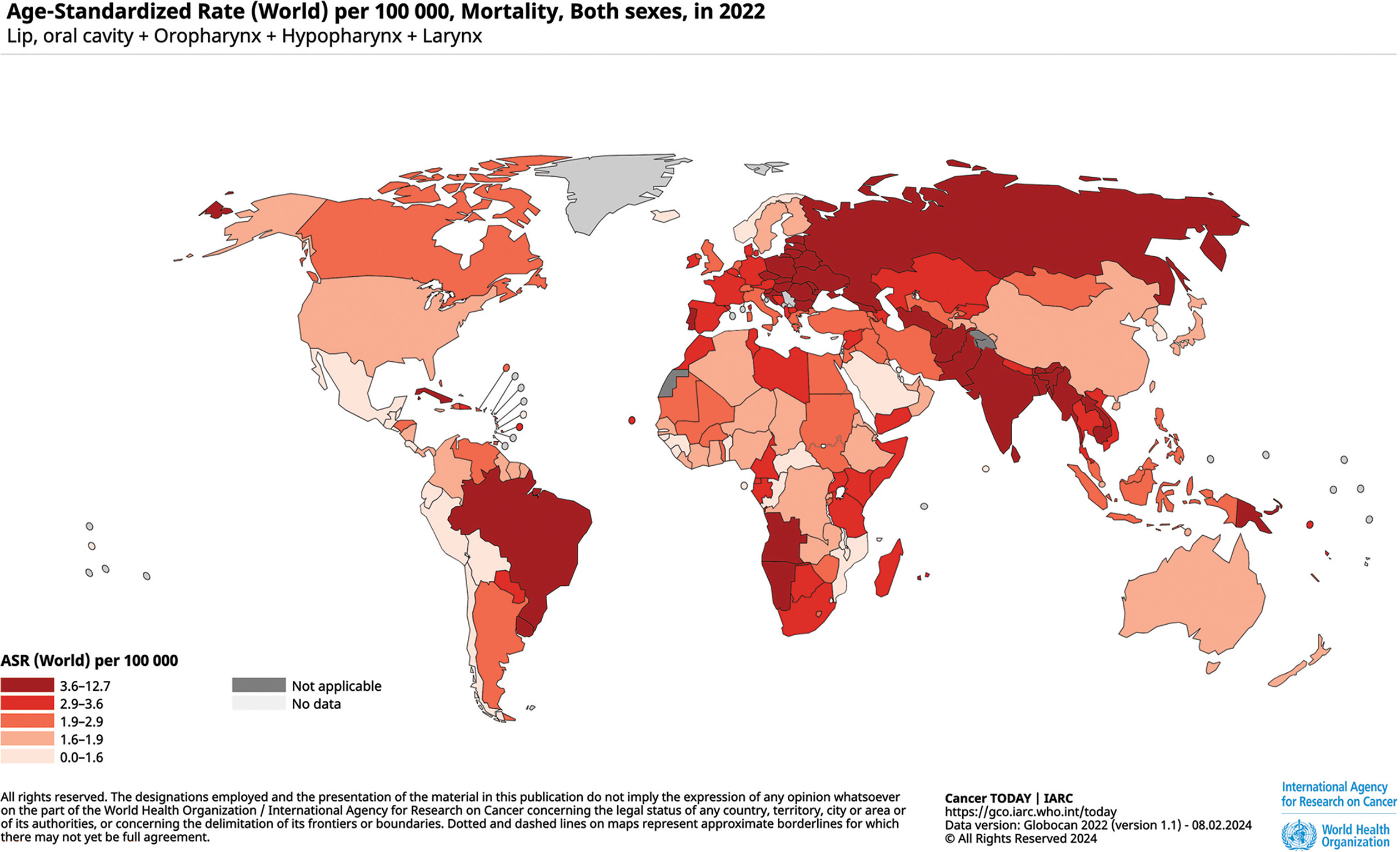

A direct consequence of this undersupply is that while the incidence of cancer ( Figure 2 ) in Africa (aside from Namibia) is less than or equal to 7.7 while in the US it is 7.7-19.5, the mortality rate in Africa is significantly higher ( Figure 3 ; up to 10.8 in multiple countries in Africa vs 1.2-1.6 in the US).

The 2022 head and neck cancer global age-standardized incidence rates. The map was generated using the GLOBOCAN website mapping tool ( https://gco.iarc.fr/today/online-analysis-map ) by selecting “lip, oral cavity,” “oropharynx,” “hypopharynx,” and “larynx” cancers.2

The 2022 head and neck cancer global age-standardized mortality rates. The map was generated using the GLOBOCAN website mapping tool ( https://gco.iarc.fr/today/online-analysis-map ) by selecting “lip, oral cavity,” “oropharynx,” “hypopharynx,” and “larynx” cancers.2

Radiologists Per Capita

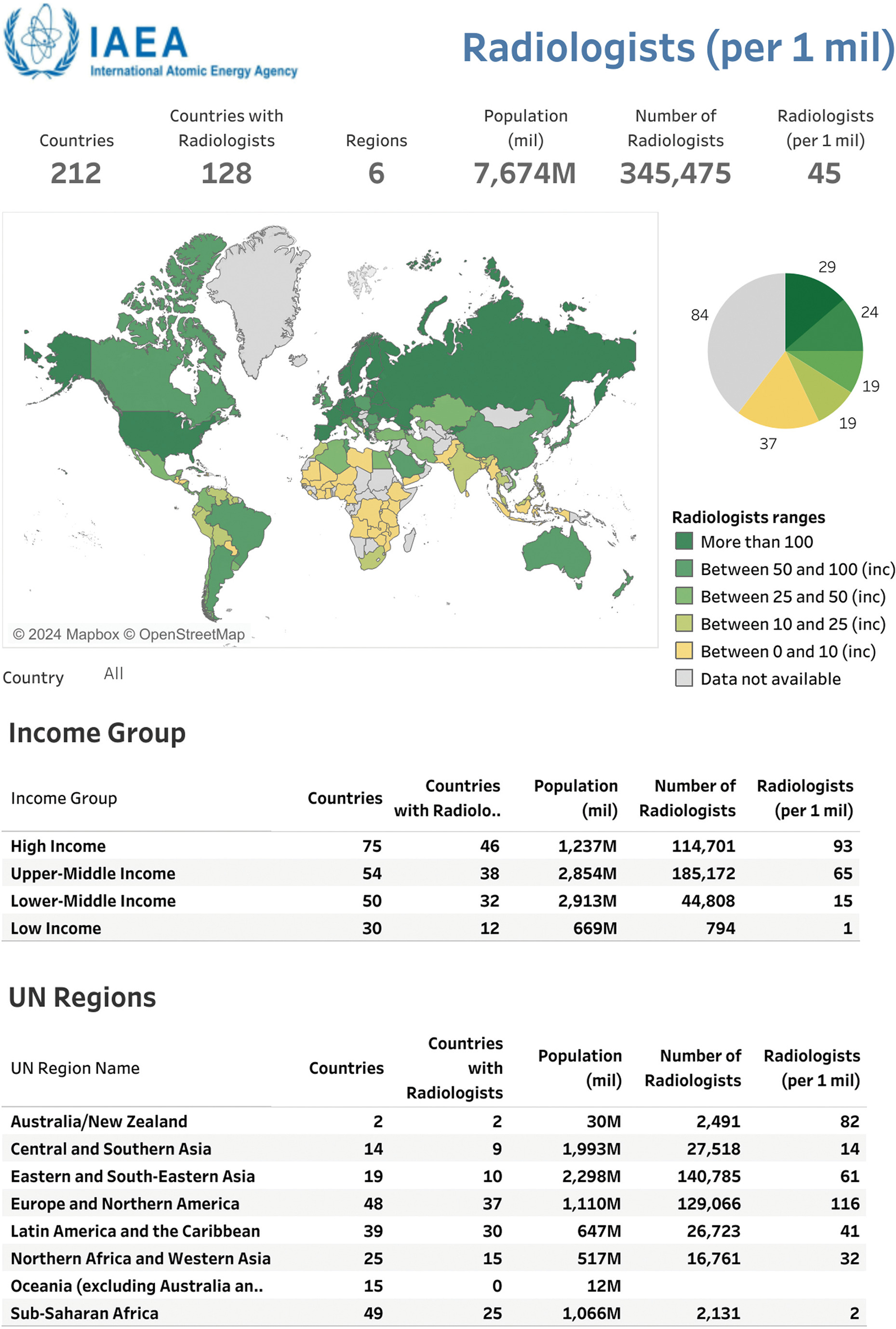

Significantly more radiologists are available to interpret head and neck PET/CT studies in HICs vs LMICs, ( Figure 4 )2 paralleling the availability of PET/CT scanners. For example, in HICs, there are 93 radiologists per million residents compared with as few as 1 radiologist per million in low-income countries. This lack of trained professionals to monitor and interpret these studies limits accessibility to this critical diagnostic imaging tool.

Radiologists per 1 million residents. Data generated from IAEA IMAGINE.6

Cost and Socioeconomic Barriers

The high cost of PET/CT scans may deter them from seeking necessary medical care or force them to choose less-effective diagnostic methods. Lack of universal health care or affordable health insurance is the biggest driver of these limitations for radiological imaging and medicine in general.10 A review of the literature found that the costs associated with head and neck cancer have only been evaluated in the US11 ; no peer-reviewed English literature articles exploring the global costs of head and neck cancer could be found.

Accessibility and Infrastructure

Accessibility encompasses factors beyond the physical presence of PET/CT scanners and cost, including geographic proximity, referral pathways, and appointment waiting times. Similarly, accessibility issues arise due to inadequate transportation infrastructure and limited health care facilities in remote areas, further exacerbating health inequalities. All of these factors cause health care inequalities.12

Strategies to Address Health Care Disparities

Improving Educational Opportunities for Global Radiology Trainees and Faculty

In the US, we have several pathways to provide subspecialized radiological education to our global colleagues, and these programs serve as terrific initiatives that other societies can emulate. For example, the Iberolatinoamerican Society of Diagnostic and Therapeutic Neuroradiology (SILAN is the Spanish acronym) offers scholarships to Latino-American or Spanish neuroradiology fellows to train at US institutions.13

The American Society of Neuroradiology (ASNR) has an international neuroradiology teaching program, the Anne G. Osborn ASNR International Outreach Professor Program, which currently operates in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.14 This program was started by sending neuroradiologists to 5 countries and has now expanded to 9 sites in 8 countries, with plans for future expansion.

Many of the faculty from these programs have formed long-lasting relationships with radiologists and trainees in their host countries.

Research

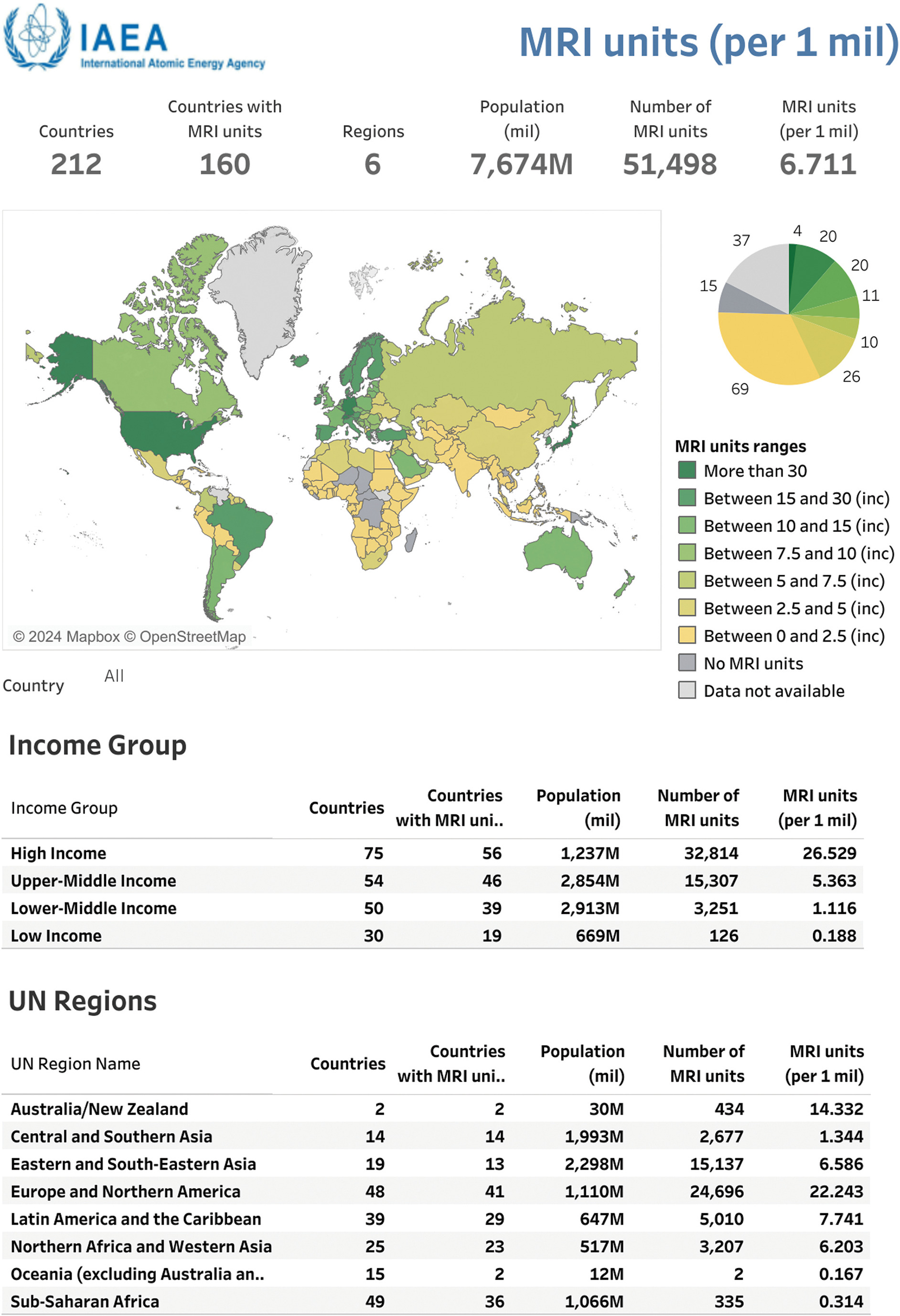

Although PET/CT is the recognized workhorse in the diagnosis and follow-up of head and neck cancers, other lower-cost imaging options are available, such as multiparametric MRI, including diffusion-weighted imaging.6, 15, 16 Specifically, in the US, a PET/CT may cost $1564 vs $956 for an MRI.17 More research is needed to standardize these MR modalities, which is especially urgent and pertinent in the global arena, as MR is more available than PET/CT ( Figure 5 ).6 For example, LMICs have 188-5363 MR scanners per million residents, significantly higher than the 0-301 PET/CT scanners per million residents, as detailed in Figure 1 .

MR scanners per 1 million residents. Data generated from IAEA IMAGINE.6

Access to More Units, Improved Infrastructure, and Better Health Coverage

Governments and health care authorities should prioritize investment in PET/CT imaging infrastructure, particularly in underserved regions and low-resource settings. Addressing these problems may involve expanding existing facilities or establishing new PET/CT centers that are more accesible to remote communities.

Improving insurance coverage or providing universal health care could also help mitigate health care disparities and adverse outcomes arising from lack of access to PET/CT imaging in countries with adequate imaging infrastructure.18

Conclusion

Health inequalities in PET/CT imaging persist between the US and other HICs and compared with LMICs, driven by disparities in the number of PET/CT scanners, cost, and accessibility. These inequities have profound implications for patient outcomes and contribute to delayed diagnosis and treatment, furthering outcome disparities. Addressing these challenges requires collaborative efforts from policymakers, health care professionals, and community stakeholders to ensure equitable access to PET/CT imaging services for all individuals. US radiologists play a unique role in driving these changes, primarily through educational outreach and novel research tools that may allow lower-cost imaging tools to detect and monitor head and neck cancers.

References

Citation

GJG P. Global Health Care Inequalities of Head and Neck Cancer Imaging and Treatment Protocols Emphasizing PET/CT Availability. Appl Radiol. 2024;(4):27 - 33.

doi:10.37549/AR-D-24-0006

August 1, 2024