Giant cell tumor of the larynx

Images

Giant cell tumor of the larynx

Findings

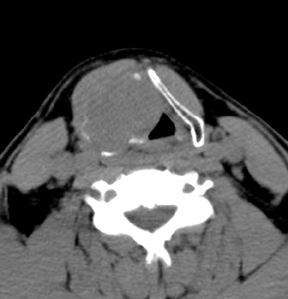

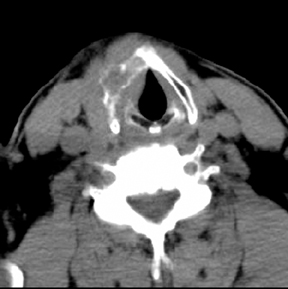

Computed tomography (CT) of the neck with intravenous iodinated contrast showed a 5 × 4 × 4-cm solid, round, soft-tissue mass with homogenous enhancement centering within the right thyroid cartilage. The right thyroid cartilaginous tissue is replaced by destructive, expansile tumor (Figure 1). The mass is extending into the inferior aspect of the epiglottis, soft tissue of the larynx and into right endolaryngeal space (Figure 2). The lesion appears to be well defined. There is no evidence of perilesional fat stranding. There is no evidence of cervical lymphadenophathy. A CT of the chest showed no evidence of primary neoplasm or distant metastatic disease.

The patient underwent right-neck fine needle biopsy and aspiration with the cytopathology report of a giant cell tumor of the larynx. He subsequently had right vertical partial laryngectomy and laryngoplasty. Pathologic analysis of the surgical specimen confirms the diagnosis of a giant cell tumor of the larynx with regional lymphovascular invasion. No adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy was provided. Postoperative follow-up for 4 months showed no evidence of recurrence or complication.

Discussion

Clinical characteristics

Giant cell tumors of the larynx (GCTL) are extremely rare benign tumors arising in the osteocartilaginous tissue of the larynx. The majority of the tumors reported in the literature arise from the thyroid cartilage (thyroid cartilage: 80%, cricoid cartilage: 15%, epiglottis: 5%) and have predilection for male (M:F =10:1), with the mean age at the presentation of 40 years.2 The site of origin has been localized to the thyroid or cricoid cartilage that is undergone endochondral ossification. The common signs and symptoms are palpable neck mass, hoarseness, airway obstruction, and dysphagia. Other symptoms include sore throat, chronic sinusitis, voice loss, and ear pain. There is no definitive association with smoking, heavy alcohol use, or radiation exposure. The duration of symptoms ranges from 1 to 9 months.2 GCTLs seem to behave less aggressively than their long bone counterparts. Although there are not sufficient numbers of cases and follow-up to accurately predict future biologic behavior of these lesions, GCTL appear to be, to date in all reported cases, non-metastasizing lesions. Complete surgical resection is adequate for local control in all the reported cases. Radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy are not a necessary adjunct in the treatment of these laryngeal tumors.

Imaging features

GCTLs are expansile, yet encapsulated, solid lesions centered within the thyroid or cricoid cartilage, with destruction and displacement of the cartilaginous tissues and extension into laryngeal space.2,3,4 The lesion is round in shape and seems to balloon out from the thyroid cartilage. This appearance distinguishes GCTL from tumors that invade the thyroid cartilage from outside, such as lymphoma, metastasis, squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx, or thyroid cancers. The tumors demonstrate homogenous contrast enhancement. GCTLs are expansile and appeared locally invasive, but there is no evidence of regional lymph node spread or distant metastasis. Enlarged tumors can cause airway obstruction and compression on adjacent structures.

Differential diagnosis for lesions that centered within the thyroid or crycoid cartilage includes giant cell reparative granuloma, brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism, osteoblastoma, chondroblastoma, chondrosarcoma, chondroma, aneurysmal bone cyst, nonossifying fibroma, foreign body reaction, benign fibrous histiocytoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, osteosarcoma with abundant giant cells, and carcinoma (including spindle cell or sarcomatoid carcinoma) with giant cells.2,10 These lesions and GCTL can be difficult to distinguish from one another radiographically. The radiographic features of GCT and aneurysmal bone cyst may overlap and will not always allow radiographic distinction. The distinction can be made histologically. Residual thyroid cartilage or new bone formation within the GCTLs sometimes can mimic chondroid or osteoid matrix of chondrosarcoma and osteosarcoma respectively.4 Regional lymph node or distant metastasis associated with sarcomatous lesions on imaging studies point to more malignant lesions and excludes GCTLs from the differential.

Due to their rarity, GCTLs are often not included in the differential diagnosis. However, GCTL should be a consideration if a large and expansile, well-encapsulated lesion that is centered within thyroid cartilage, in middle-age men, without evidence regional or distant metastasis, is found on imaging studies. A GCTL may simulate a malignant neoplasm because of the large tumor size and rapid growth, but accurate biopsy interpretation is necessary for definitive diagnosis and save the patient from unnecessary radical surgery and adjuvant therapy.

Pathologic features

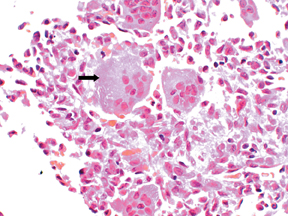

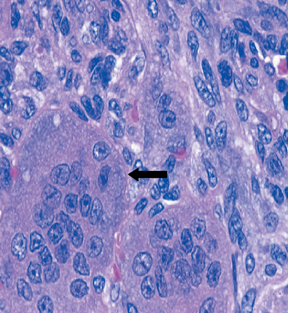

Histologically, GCTLs are submucosal and are confined by the surface epithelium. There is no surface ulceration. Infiltrative growth pattern and lymphovascular invasion may be identified, but there is no evidence of spreading outside of surface epithelium.1 This could explain for encapsulated appearance radiographically and benign or indolent nature of these tumors clinically. All lesions demonstrated the typical histologic features of GCTs of skeletal bone.2 Microscopically, multinucleated giant cells were found dispersed regularly among the mononuclear spindle cells stroma, without any areas of aggregation. These mononuclear stromal cells are predominantly round, oval or polygonal in shape and can resemble normal histiocytes. The nuclei of the spindle cells are indistinguishable and very closely resemble those within the multinucleated giant cells, a feature that can be helpful in separating this entity from other lesions in the differential diagnosis.5 Although mitoses are frequently noted in the spindle cells, there are no atypical mitotic figures or pleomorphism identified. There are areas of bone formation by endochondral ossification.1 As in the giant cell tumors of long bones, these tumors contain a large number of giant cells in a diffuse distribution. Although the presence of giant cells can suggest a GCT, careful clinicoradiologic correlation and microscopic evaluation of the mononuclear component are required to exclude other entities that also contain giant cells.

Giant cell reparative granuloma and brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism contain areas of aggregated giant cells that have less nuclei-per-cell than those in the GCT and have a more fibrotic stroma with more prominent hemorrhage and hemosiderin deposition than the GCT.9,12 A clear-cut distinction is not always possible, but in general, giant cell tumor contains a more uniform distribution of larger giant cells with many more nuclei per cell. Aneurysmal bone cyst, with associated giant cell tumor, usually contains large solid areas of the typical giant cells.11

Osteoblastoma, chondroblastoma, and benign fibrous histiocytoma contain fewer and smaller giant cells compared to GCTs. Examination of the cellular stroma allows further distinction. Benign fibrous histiocytoma has predominant pattern of storiform, cellular fibrous-tissue stroma. Osteoblastoma has increased cellularity with haphazard proliferation of prominent, although loose, intervening fibrovascular-tissue stroma and interlacing trabeculae of osteoid. Chondroblastoma contains islands of cartilage amid a mononuclear cell background. The mononuclear cells of chondroblastoma have a moderate amount of amphophilic cytoplasm and grooved, indented nuclei, with pericellular calcifications in a so-called chicken-wire pattern. The histologic features of nonossifying fibroma with spindle stromal cells, fibrosis, and aggregates of foamy macrophages allow easy separation from GCTs. A foreign body giant cell reaction will contain giant cells, but not a mononuclear cell stroma.10

Pleomorphism and cellular atypia allow separation of ostesarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and carcinoma with giant cells from GCT.7,8 Radiographic features of osteosarcoma with heavy mineralization are also useful for differentiation. Immunohistochemical studies to define the stromal cells and/or giant cells are also helpful if the distinction is not clear.

Conclusion

GCTL are extremely rare tumors, usually presenting in middle-aged male patients with obstructive symptoms. The tumors arise from the cartilages (thyroid most frequently) of the larynx in areas of endochondral ossification, with a typical histology of numerous giant cells containing many nuclei that are histologically indistinguishable from the nuclei of the stromal spindle cells surrounding the giant cells. These tumors can present a challenge both in radiologic diagnosis due to their rarity, and in pathologic diagnosis due to similarities with other more common reactive, benign, and malignant neoplastic conditions. The feature of multiple multinucleated giant cells dispersed regularly within the spindle-cell stroma allows histologic distinction from many other giant cell-containing processes. The nonmetastasizing and encapsulated features help narrowing the differential radiographically.

Differentiation of GCTL from other cytologically malignant giant cell-rich tumors is critical in terms of treatment and prognostic implication. Complete but conservative surgical excision is the treatment of choice, with attempts to preserve the quality of the voice and speech if at all possible. Adjuvant therapy is unnecessary for these tumors.

- Soya P, Yoon-Mee J, Woo-Ick Y, et al. Giant cell tumor of the larynx: Report of a case. Korean J Pathol. 1997;31:75–78.

- Wieneke JA, Gannon FH, Heffner DK, Thompson LD. Giant cell tumor of the larynx: A clinicopathologic series of eight cases and a review of the literature. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:1209–1215.

- Hinni ML. Giant cell tumor of the larynx. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109: 63–66.

- Martin PC, Hoda SA, Pigman HT, Pulitzer DR. Giant cell tumor of the larynx. Case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1994;118: 834–837.

- Werner JA, Harms D, Beigel A. Giant cell tumor of the larynx: Case report and review of the literature. Head Neck. 1997;19:153–157.

- Devaney KO, Ferlito A, Rinaldo A. Giant cell tumor of the larynx. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1998;107:729–732.

- Kuwabara H, Saito K, Shibanushi T, Kawahara T. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the larynx. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1994; 251:178–182.

- Yiotakis J, Ferekidis E, Papadimitriou N. Chondrosarcoma of the thyroid cartilage. Oto-Rhino-Laryngologia Nova. 2002/2003;12: 311-313.

- Perrin J, Zaunbauer W, Haertel M. Brown tumor of the thyroid cartilage: CT findings. Skeletal Radiol. 2003;32:530–532.

- Batsakis JG, Raymond AK. Cartilage tumors of the larynx. South Med J. 1988;81:481–484.

- Della Libera D, Redlich G, Bittesini L, Falconieri G. Aneurysmal bone cyst of the larynx presenting with hypoglottic obstruction. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:673–676.

- Murphey MD, Nomikos GC, Flemming DJ, et al. From the archives of AFIP: Imaging of giant cell tumor and giant cell reparative granuloma of bone: Radiologi-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2001;21:1283-1309.