Common Thyroid Medicine Associated with Bone Loss

Images

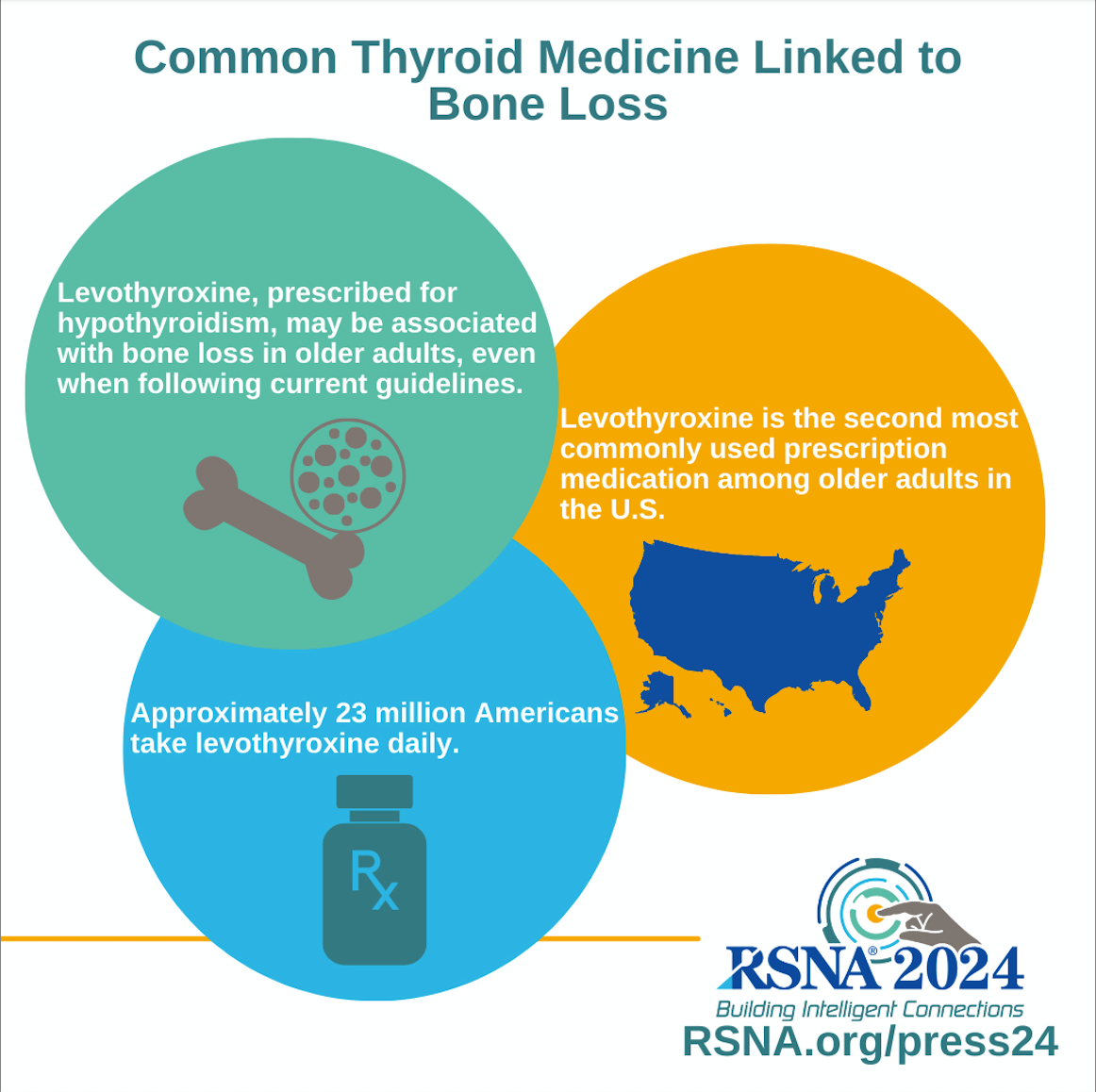

The second most commonly prescribed medication among older adults in the US, Levothyroxine, may be associated with bone loss, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

Levothyroxine, marketed under multiple brand names including Synthroid, is a synthetic version of a hormone called thyroxine and is commonly prescribed to treat the condition hypothyroidism, or underactive thyroid. In people with hypothyroidism, the thyroid gland does not produce enough thyroxine on its own, often resulting in fatigue, weight gain, hair loss and other symptoms. If left untreated, hypothyroidism can lead to serious and potentially fatal complications.

Approximately 23 million Americans—about 7% of the US population—take levothyroxine daily. Sometimes, patients have been taking levothyroxine for many years, but it is not clear why it was initially prescribed or if it is still required.

“Data indicates that a significant proportion of thyroid hormone prescriptions may be given to older adults without hypothyroidism, raising concerns about subsequent relative excess of thyroid hormone even when treatment is targeted to reference range goals,” said the study’s lead author Elena Ghotbi, MD, postdoctoral research fellow at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Though there are some variables, a normal reference range for thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is typically around 0.4 – 5.0 microunits per milliliter. Excess thyroid hormone has been associated with increased bone fracture risk.

For this study—a multidisciplinary collaboration between the Russell H. Morgan Department of Radiology and Radiological Science and Endocrinology Department at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Dr Ghotbi and colleagues aimed to determine whether levothyroxine use and higher thyroid hormone levels within the reference range are associated with higher bone loss over time in older “euthyroid” adults, meaning adults with normal thyroid function.

The researchers used the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA), a prospective observational cohort study of community-dwelling older adults. Participants aged 65 and older who had at least two visits and thyroid function tests consistently within the reference ranges were included in Dr Ghotbi’s study.

“This research is a collaboration between Johns Hopkins and the BLSA, the longest-running study on aging conducted by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging,” said co-author Eleanor Simonsick, PhD, epidemiologist and BLSA co-director. “The BLSA’s extensive data include repeated DEXA measurements at each study visit, which provides valuable insight into the progression of bone density and bone mass changes over time, offering a more comprehensive understanding of aging-related osteoporosis.”

The study group included 81 euthyroid levothyroxine users (32 men, 49 women) and 364 non-users (148 men, 216 women), with a median age of 73 and TSH levels of 2.35 at the initial visit. Other risk factors like age, gender, height, weight, race, medications, smoking history and alcohol use were considered in propensity score matching of levothyroxine users versus non-users.

The results showed that levothyroxine use was associated with greater loss of total body bone mass and bone density—even in participants whose TSH levels were within the normal range—over a median follow-up of 6.3 years. This remained true when taking into account baseline TSH and other risk factors.

“Our study suggests that even when following current guidelines, levothyroxine use appears to be associated with greater bone loss in older adults,” said Shadpour Demehri, MD, co-senior author and professor of radiology at Johns Hopkins.