Anterior Sacral Meningocele

Case Summary

A toddler presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain. The patient had a history of constipation and recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs). The patient had no neurologic deficits. Recent pelvic ultrasound in the community demonsrated a large cystic pelvic mass.

Imaging Findings

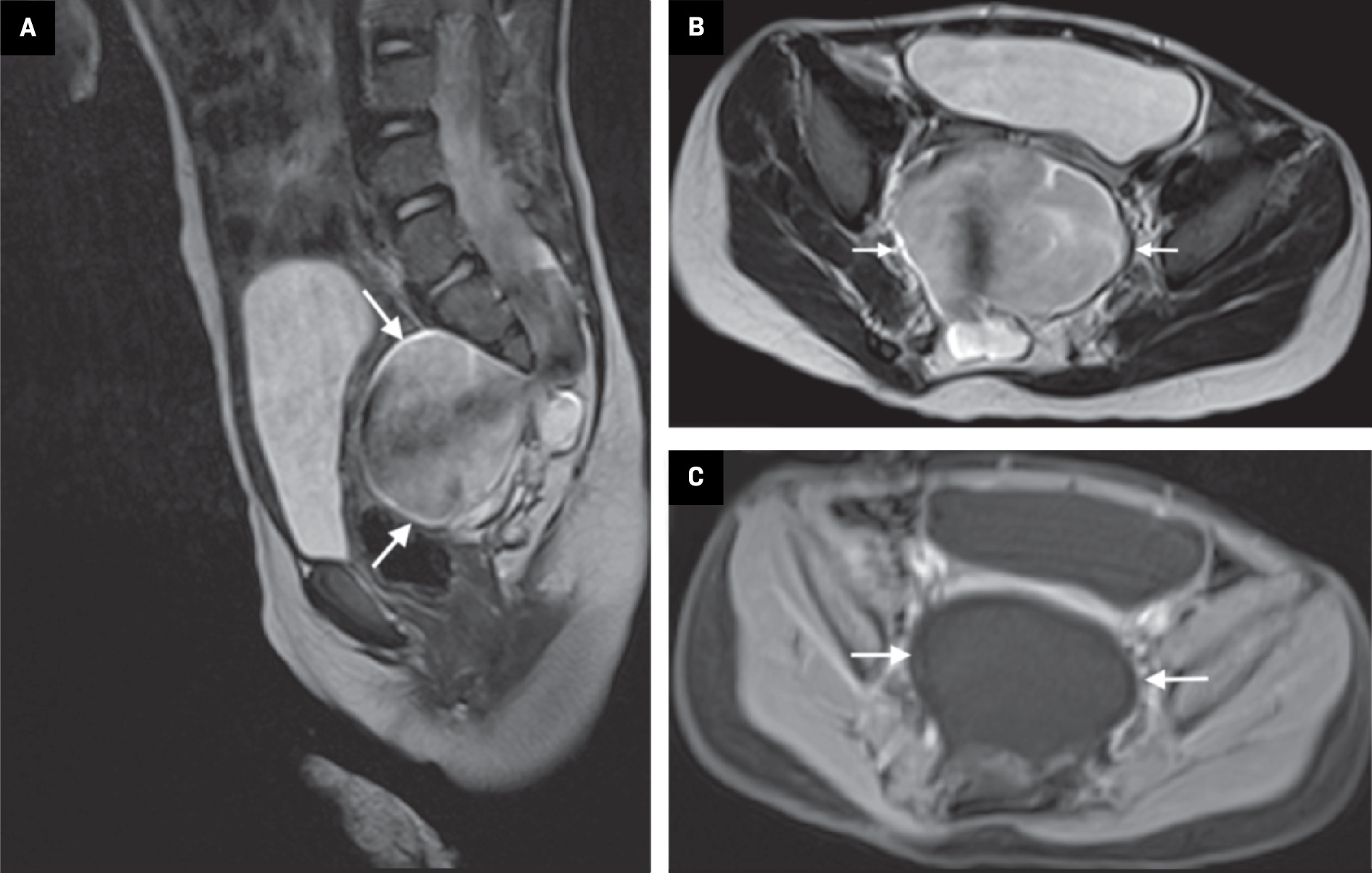

Pelvic MRI ( Figure 1 ) demonstrated a large, ovoid, well-circumscribed fluid collection in the presacral space that was contiguous with the spinal subarachnoid space through an osseous defect in the sacrum. There was turbulent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow within the presacral collection. The features were overall in keeping with an anterior sacral meningocele (ASM). There wasassociated mass effect on regional structures, including anterior displacement and partial attenuation of the rectum and urinary bladder. The sacrum appeared dysplastic, with partial agenesis of the inferior sacrum. No anorectal malformation was identified.

Pelvis MRI. (A) Sagittal T2 demonstrates a large, heterogeneous fluid collection in the presacral space (arrows) that communicates with the spinal canal through a hypoplastic sacrum, which terminates at the S2-S3 level. ( B ) Axial T2 shows the defect in the sacrum and turbulent CSF flow within the presacral collection (arrows). ( C ) Axial T1 fat-saturated post-contrast sequence demonstrates no enhancing solid component in the meningocele.

Diagnosis

Anterior sacral meningocele.

The differential diagnosis includes sacrococcygeal teratoma, neuroenteric cyst, sacral chordoma, cystic neuroblastoma, rectal duplication cyst, and ovarian cyst.1

Discussion

Anterior sacral meningocele is a hernia of the dural sac through a defect in the ventral sacral wall1 and can be categorized as acquired or congenital. The most common causes of acquired sacral meningoceles include Marfan syndrome, neurofibromatosis type 1, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, all of which lead to dural ectasia.1, 2 Congenital forms of ASM are the most common and can be either familial (X-linked dominant) or occur sporadically.1, 3

The pathogenesis of congenital ASM can be traced to the secondary neurulation during embryogenesis, where the sacral segments of the spinal cord from S2 to the coccyx are formed from a mass of pluripotent stem cells referred to as the caudal eminence.4 Malformation of the sacral segments in association with CSF pulsations leads to the extension of the meninges out of the sacral spinal canal, typically at the level of the S1-S2 junction, and into the retroperitoneal space, forming an ASM.1 The caudal eminence gives rise to multiple other structures, including the hindgut. As a result, sacral malformations leading to ASM are frequently associated with other congenital defects involving the urogenital or hindgut structures.1 Anterior sacral meningocele may be associated with Currarino syndrome, a triad of presacral mass (typically ASM or teratoma), anorectal malformation, and sacral bony defect.5

Patients commonly diagnosed with ASM include those with long-standing complaints of constipation, gynecological or obstetrical manifestations, and neonates who present with other congenital defects such as those seen in Currarino syndrome.6 The signs and symptoms associated with ASM are related to its impact on surrounding genitourinary organs (eg, dysuria, UTIs, polyuria, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia), reproductive organs (eg, dystocia and meningocele sac rupture), and colorectal (eg, constipation or obstipation) and neurological dysfunctions (eg, compression of the nerve roots exiting from the sacrococcygeal region leading to pelvic pain, radicular pain, and paresthesia).1, 6 Compression of ASM from Valsalva maneuvers or postural changes can affect the CSF flow, resulting in headaches.2 The clinical signs associated with ASM include retro-rectal mass, which can be palpated on a digital rectal examination in nearly all patients.1 Patients may also present with other congenital anomalies such as vaginal duplication, anal stenosis, anal atresia, sacral bone defect (scimitar sign), club foot, and leg-length discrepancies.1

The diagnosis of ASM can involve the use of multiple modalities, including radiographs, US, CT, and MRI.1 Features that should be evaluated include the identification of the neck of the ASM, abnormalities of the meninges and vertebral components of the sacrum such as sacral defect; cystic nature of the mass; the relationship between the meningocele and the sacral nerve roots; and the relationship between the pelvic viscera and the meningocele.7 Radiography is useful in detecting the scimitar sign, which appears as a unilateral sickle-shaped distortion of the sacral bone.7 Ultrasound can help identify the contents of the presacral mass and enlargement of the meningocele sac.8 CT can help identify the communication of the subarachnoid space and may help differentiate ASM from other solid masses in the presacral location.9 The modality of choice to diagnose ASM is MRI.1 It can help identify other associated anomalies such as spinal cord tethering.1 Meningocele has the same signal intensity as the CSF and a thickened filum terminale, with or without fatty infiltration, may be present.1 The management of ASM is surgical, which involves obliteration of the communication between the meningocele and the subarachnoid space.1

Conclusion

Anterior sacral meningocele most commonly results from a malformation in which the meninges protrude through a developmental osseous defect in the sacrum. Patients may present with associated abnormalities of other genitourinary structures. The most useful imaging modality to diagnose ASM is MRI, which will reveal communication between the meningocele and the spinal subarachnoid space. The treatment of ASM is surgical.

References

Citation

Naqvi S M, Asim S A, BSc MSc. Anterior Sacral Meningocele. Appl Radiol. 2024;(00):39 - 41.

doi:10.37549/AR-D-24-0008

August 1, 2024