Technology and Industry: Breast-specific gamma imaging

Radiologists have long known that the presence of dense breast tissue can increase the risk of breast cancer by masking some lesions on mammographic images. A new study has shown that having dense breast tissue¨C¨Cin and of itself¨C¨Cputs women at an increased risk for developing this disease. 1 The study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in January 2007, concluded that "after adjustment for other risk factors, extensive mammographic density was strongly and reproducibly associated with an increased risk of breast cancer." 1

The study, conducted on 1112 case-control pairs, "examined the association of the measured percentage of density in the baseline mammogram with risk of breast cancer." The authors found that, relative to women with density in <10% of the mammogram, those with density in 75% had a 4.7% increased risk of breast cancer. In an accompanying editorial, Kerlikowske 2 noted that "increased mammographic density is strongly associated with increased susceptibility to breast cancer and decreased detection of cancer by mammography." She further stated that "the time has come to acknowledge breast density as a major risk factor for breast cancer."

"The basic summary is that the presence of a pattern of very dense breast tissue versus fatty replaced breasts in a patient of the same age results in a nearly fivefold independent risk factor for breast cancer," explained Ted Fogarty, MD, Staff Radiologist at Medcenter One Hospital, Bismarck, ND, and Chairman of Radiology, North Dakota School of Medicine & Health Sciences. This increased susceptibility, combined with the difficulties in visualizing cancers in a mammogram of dense breast tissue, creates a diagnostic problem.

Using data from the study, Fogarty presented the following example. "If you are 60 years old and have extremely dense tissue, a radiologist has a 3 out of 1000 chance of missing your cancer. If you are 59 and you have an almost entirely fatty replaced breast pattern, only 0.1 out of 1000 mammograms will legitimately miss your cancer. That's a 30-fold difference in the rate of missed cancers. It seems completely disingenuous and dishonest for us as a radiology community to have to say ¡®negative mammogram, BI-RADS category 1' in both instances when there is no change over time," he contends. "To me, a 60-year-old with an extremely dense pattern just has a mammogram that doesn't show cancer."

Breast-specific gamma imaging

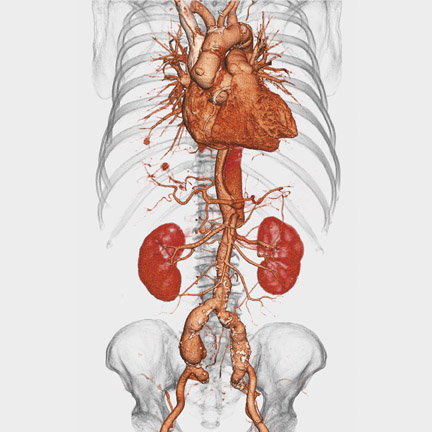

One way to overcome the challenges presented by dense breast tissue is to employ functional, rather than anatomic, imaging techniques. Breast-specific gamma imaging (BSGI) is a functional imaging modality that employs a gamma camera that was specifically designed to replicate mammographic views.

"The examination is performed in a manner very similar to a mammogram," said Jean M. Weigert, MD, Director of Women's Imaging at Mandell and Blau MDs PC, New Britain, CT, who has been performing BSGI since the Dilon 6800 (Dilon Technologies, LLC, Newport News, VA) was installed at the Hospital of Central Connecticut's Bradley Memorial Campus (Southington, CT) in June 2005. "The images are taken so that you get the same views¡ªcraniocaudal and mediolateral oblique¡ªas with mammography. Then, if there is a specific area in question, the user can focus in a little more clearly by moving the camera to the specific site in question. During the examination, the breast is supported between the camera and a top plate without much compression, making it very comfortable for patients (Figure 1). Prior to starting to image, an injection of the radioisotope sestamibi is given, and then the images are obtained. Each image can take 5 to 10 minutes to acquire, depending on the protocol used. The results are generated on a computer screen and can be manipulated and/or printed."

When mammographic findings are not definitive, BSGI is commonly used as an adjunct tool (Figure 2). "I like to perform BSGI in patients for whom we've done a full diagnostic work-up and we still don't have an answer," said Weigert. Other indications include assessing disease extent in patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer, patients with a history of breast cancer who have a complicated mammogram with dense tissue or scarring in the breast, and patients with implants if there are any complicated mammograms. "Basically, it is very helpful for patients who have very dense breast tissue for whom you cannot resolve a finding that is new or different and for whom doing additional views and ultrasound do not resolve the answer," she said.

Incidental findings and effect on biopsy rates

Use of BSGI can, at times, reveal incidental findings that can affect treatment. "That is very important in terms of women with very dense breast tissues who have, for example, a strong family history or a prior history of breast cancer," said Weigert. "You may be working them up for something you're concerned about in one breast and find intense uptake in the contralateral breast. You may find that there is a cancer or some other abnormality in that breast that needs further evaluation. Also, in patients who have a new diagnosis of breast cancer, not only do you want to see the extent of disease in the ipsilateral breast but also whether there is contralateral disease."

"If you recognize just how vastly different mammography is between very easy-to-read patterns and very hard-to-read patterns, it's almost an intuitive, obvious point that this is how you get around those dense tissues," added Fogarty, who began using BSGI with the Dilon 6800 in January 2006. "Then you not only diagnose the cancer you are looking for but may also find something else."

"What was really striking in our most recent Mammography Quality Standards Act (MQSA) audit was that in the 3 years prior to the initiation of BSGI, we caught about 8 or 9 cancers in 1000 exams in our screening population," said Fogarty. "In 2006, we hit 14 per 1000. I don't know if there is any place in the country where a community radiologist can say that in 1 year we went from 57 cancers caught in 2005 to 94 in 2006.

Fogarty also reported an increase in the positive predictive value for breast biopsies. "Our positive predictive value has gone from between 20% and 25% during the last 3 years on our MQSA audit to almost 50%. In other words, we have half as many negative biopsies."

"There are still false positives with BSGI," said Weigert. "The false positives we are finding are very high metabolic activity in fibrocystic tissue, frequently in patients who are premenstrual, so we like to do this test in the first 10 days of the cycle. Certain tumors such as fibroadenomas may have uptake, as well as certain papillary lesions, fat necrosis, radial scars, and other benign lesions. You might still do a biopsy with a negative outcome, but if there's uptake you'd still like to make sure there's nothing going on."

Fogarty agreed that hormonal influences must be carefully considered. "Early on, we were not timing our exams well to hormonal status, which gave us some heterogeneous physiologic uptake patterns that we didn't know what to do with," he said. "So we brought the patients back at no charge in order to time their hormones better. Now we have a tight window. We like to perform BSGI within the first 5 days of the menstrual cycle and if it's completely inconvenient to make it within the 5 days, we go closer to 10 days."

Learning curve

"For the radiologist, the learning curve is shorter for a BSGI than it is for a mammogram," Fogarty said. "BSGI is very easy compared with the learning you have to go through to figure out how to really be good at mammography."

"There is always a learning curve," agreed Weigert, "but it's not that bad. Either there's uptake or there isn't uptake. If there's uptake, you work it up further. If there isn't uptake, you decide how you are going to handle that patient."

The learning curve is not steep for the technologists either, according to Fogarty. "Using mammography techs, the learning curve is not bad. I would caution anyone against using nuclear medicine technologists for doing the actual examination because positioning is so critical in breast imaging. Those who understand the mammographic images and the mammographic positioning from a technologist's point of view will understand what is going on much more quickly."

Regulatory issues

One issue that may be off-putting for a smaller practice is the need for Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) licensing because of the use of the radiotracer. Weigert, who has a BSGI system in her private office, has been through the process. "It really wasn't as complicated as I thought it was going to be," she noted. "We had to set up a little ¡®hot lab' and get an NRC license. There's paperwork to fill out, and we had to have a physicist help us set up."

Looking forward

While BSGI is currently used only as an adjunct detection method, Fogarty envisions a future in which this technology could be used as a screening tool in a subset of women who are at particularly high risk for breast cancer and who are difficult to diagnose mammographically. He proposes using the Gail Criteria 3 as a means to stratify risk for breast cancer. If a patient's risk is high enough, then he proposes that she undergo BSGI as a secondary screening tool. "If the Gail Criteria were used to codify when it would be appropriate to do a screening BSGI, I think it would be a very powerful thing," he said.

"BSGI doesn't answer every question ¨C¨Cnothing is 100% in this world," concluded Weigert, "but I think it gives us more information in a fairly simple manner."