Recognition and treatment of acute contrast reactions

Images

Dr. Bush is a Professor of Radiology, University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, WA; and Dr. Segal is a Clinical Professor of Radiology and Urology, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY.

About 3% of patients who receive nonionic, lower-osmolality monomeric contrast media (LOCM) will experience a contrast reaction, though the vast majority of reactions are mild and require no treatment. However, about 1 in 1600 (0.06%) of patients receiving LOCM will need treatment for a reaction and a severe life-threatening reaction occurs with about 1 in 2500 patient injections (0.04%). Key to treating a contrast reaction is recognition of the type of reaction. Patient manifestations of reactions can be generally divided into 3 main categories: the uncomfortable patient; the subdued, poorly responsive patient; and, the anxious and agitated patient. In general, the more quickly a contrast reaction is recognized, correctly diagnosed and treated, the better the result—with less medication. Therefore, the goals of management should include early detection, the necessary multitasking to understand the type of reaction, and initiation of appropriate treatment as soon as possible.

This article reviews some mechanisms of reactions, the clinical presentations of the various reactions, and outlines an approach and recommended medications for dealing specifically with each reaction type.

Mechanism of contrast allergy

The exact causal mechanism of contrast-induced anaphylactic reactions is still debated. From his extensive research, Elliot Lasser1 has proposed a mechanism in which the large contrast-containing molecule causes an overload effect on the antigen-binding sites on immunoglobulin E (IgE) of mast cells and basophils and does not bind directly to an antigen-specific site. This effect varies with the particular contrast medium. Since the immuno-globulin binding is nonspecific, the resultant reaction depends on the quantity of circulating IgE and mast cells at the time the contrast medium is administered. This nonspecific binding helps explain why patients with strong allergic history are at particular risk and why prior exposure to the contrast agent is not necessary for a reaction to occur.

Other considerations are that direct contact of the contrast agent with the endothelium of blood vessels may activate Factor XII;this substance in turn activates kallikrein; kallikrein activates bradykinin; bradykinin activates prostaglandin and the leucotrienes.1,2 Leucotrienes are similar in their action to histamine, but are multifold more potent and not blocked by antihistamines. Bradykinin can mimic all the significant pathophysiological effects of histamine but is far more potent and, again, this sequence of events would not be blocked by antihistaminic drugs.

Incidence of allergic reactions

Although 3% of patients who receive nonionic LOCM will experience a contrast reaction, the vast majority of reactions are mild and require no treatment.2,3 Moderate reactions, such as bronchospasm or hypotension, occur with approximately 1 of 250 patient injections(0.4%). Severe, life-threatening reactions are very uncommon, occurring with 1 in 2500 patient injections (0.04%).4 Experience at the Mayo Clinic (reported by Hunt et al., at the 2007 meeting of the Society of Uroradiology) is that 0.06% (1 in 1600) of patients receiving LOCM needed treatment for a reaction and about 0.02% (1 in 5000) receiving gadolinium agents needed treatment for a reaction. With the newer nonionic iso-osmolality dimers, acute idiosyncratic reactions seem to occur about as frequently as with the monomeric LOCM; some nonionic dimers have an increased frequency of delayed reactions, though most are thought to be mild.

Today, occurrence of a fatal reaction is much less frequent than 30 years ago. Exact numbers are difficult to obtain, but using the largest series of reported reactions, the risk of a fatal reaction after an injection of iodinated LOCM is approximately 1 in 170,000 injections.4 The change in fatal reactions over the past 30 years from a rate of 1 in 30,000 injections to 1 in 170,000 likely reflects the increasing use of nonionic LOCM and the increased training of radiologists and radiology personnel about the recognition and treatment of reactions.

Manifestations of acute contrast reactions in patients

Key to treating a contrast reaction is recognizing the type of reaction. Patient manifestations of reactions can be generally dividedinto 3 main categories: the uncomfortable patient; the subdued, poorly responsive patient; and, the anxious and agitated patient.5

Uncomfortable but calm patients typically are experiencing nausea, vomiting, hives, itching, and redness.

Poorly responsive, subdued, or unresponsive patients usually are hypotensive or hypoglycemic.

Anxious or agitated patients are hypoxic, either due to bronchospasm, edema of airways, laryngeal edema, or possibly pulmonaryedema.

Recognizing these signs and the patient’s behavior helps identify the exact reaction, and thereby, the most effective treatment. The reactions to gadolinium agents and treatment of these reactions are exactly the same as those due to iodinated contrast agents; they occur much less frequently.

Signs and symptoms

Nausea and vomiting is less common with nonionic LOCM. It is rarely of significance, however, it may be the initial component of a more serious reaction. These reactions occur more frequently with some gadolinium agents.

Urticaria/hives, itching, and/or diffuse erythema are more common than nausea and vomiting. They vary in severity and may be a component of a more generalized, acute systemic reaction. These should be treated symptomatically if they occur as an isolated event.

Angioedema and airway narrowing are significant reactions. A contrast reaction presenting with angioedema of the face and lips should alert the radiologist that edema of the lower airway, including the larynx, may also be occurring.

Laryngeal edema is a serious, life-threatening event requiring prompt and aggressive treatment. This is the “anxious patient” and symptoms include coughing, attempts to clear the throat, hoarseness, squeaky voice, and a sense of having a lump in the throat. This patient has difficulty taking air in. These patients are usually very agitated as they feel they are being suffocated or smothered.

Bronchospasm resembles the classic asthma attack. This is seen as an anxious patient, and symptoms include chest tightness, shortness of breath and wheezing. The patient has difficulty getting air out. These patients often have a history of similar attacks.

Hypotension with responsive tachycardia usually is a component of an acute, generalized systemic anaphylaxis-like reaction. It can complicate and slow absorption of treatment medications given to treat the reaction. A caveat: marathon runners and patients on beta-blockers may have a slow pulse without having a true vaso-vagal reaction.

Hypotension with vagal-induced bradycardia (vaso-vagal reaction) is seen in patients presenting with symptoms of hypotension plus a very slow heart rate. The patients are calm, subdued, diaphoretic, and have cool skin. Since these patients are already supine/recumbent in the scanner, the severity of the reaction encountered in radiology is usually much worse than when a vaso-vagal reaction or fainting spell occurs in an upright patient. A key to this diagnosis is recognizing the bradycardia.

Acute, generalized systemic reactions usually have many of the above components—hives, redness, angioedema, airway compromise,hypoxia, and hypo- tension. This reaction can progress rapidly, and therefore, requires early, active and aggressive treatment.

Acute pulmonary edema is uncommon, but may be due to a reaction directly in the airways and lungs, or it may reflect cardiac decompensation and/or myocardial infarction.

Cardiopulmonary collapse and/or cardiac arrest can occur suddenly without preliminary signs. It might evolve rapidly from initial nausea and vomiting or from a moderate contrast reaction to complete cardiovascular collapse.

Adverse effects in children

Children have a lower incidence of contrast reactions. The reactions that they experience tend to be anaphylaxis-like and/or involve the airway.6 Children have strong hearts, so cardiovascular-type reactions are very uncommon.

Nonvascular routes of administration and acute contrast reaction

Both high-osmolality ionic (HOCM) water-soluble contrast and LOCM are used to opacify the GI tract if barium is not desired. If iodinated contrast is absorbed into the bloodstream, the risk of an allergic-like contrast reaction can be just as significant and severe as if the iodinated contrast were administered directly intravascularly. Contrast media are absorbed rapidly from the peritoneal cavity or severely inflamed intestinal mucosa. Situations of potential significant absorption occur when water-soluble iodinated contrast is used to opacify the GI tract in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, bowel perforation, and potentially during high-grade intestinal obstruction when ischemia of the bowel wall is present. Reactions can be similar in presentation and severity as when they occur after intravascular administration.

Anaphylactic-like reactions are not considered to be dose-related. Therefore, other routes of administration that might lead to systemic absorption and an allergic-like, acute contrast reaction include any of the following, particularly in the presence of intravasation: endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERCP) with aggressive injection; retrograde ureteropyelography with injection that results inpyelovenous backflow and/or retrograde urethrography; extensive leak into the retroperitoneum or during hysterosalpingography; and cystography with bladder rupture or leak.

Recognition of acute contrast reactions

In general, but not always, the more quickly a contrast reaction is recognized, correctly diagnosed and treated, the less medication is required to achieve better results. Therefore, the goals should include early detection and the necessary multitasking to understand the type of reaction and to initiate appropriate treatment as soon as possible. Below is an action plan to help identify and manage contrastreactions.

Basics

- Quickly assess the situation.

- Call for assistance: The type of assistance will be determined by the initial assessment.

Initial assessment

- Look critically at the patient.

- Get vital signs and obtain a pulse.

- Talk with the patient.

Evaluate the the patient

- Acuity of their condition.

- Is there any facial, eyelid or lip edema?

- Are hives present?

- Is there any hoarseness that was not present before the exam?

Obtaining a pulse is important because a palpable radial pulse equates to a systolic blood pressure of between 80 to 90 mmHg. Taking the pulse allows rapid assessment of tachycardia or bradycardia. This information helps differentiate between the vaso-vagal reaction with associated bradycardia and the compensatory tachycardia response of usual hypotension.

Talking with the patient will help determine if:

- They are oriented to name and place.

- They are short of breath.

- They are coughing, struggling to get air in or experiencing inspiratory stridor.

- They are wheezing or trying to get air out (i.e. bronchospasm).

- They are just short of breath without inspiration or exhalation signs, and therefore, may have congestive failure or noncardiac pulmonary edema (you may hearrales with or without a stethoscope).

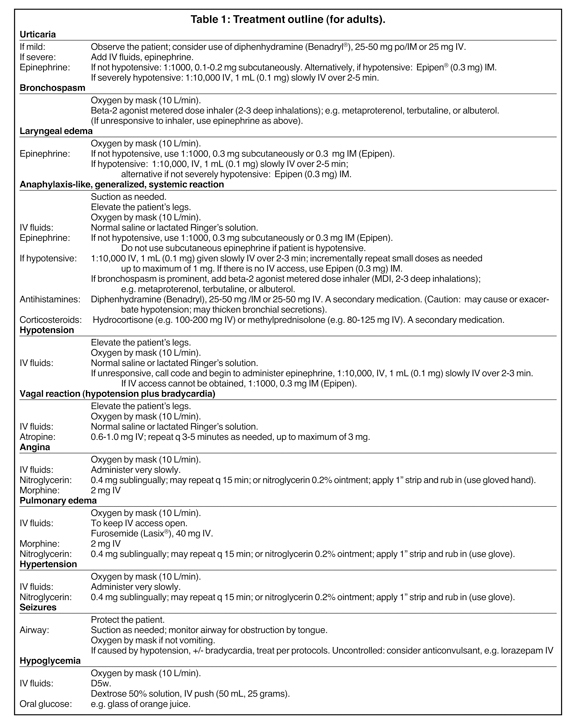

When an acute contrast reaction is identified there are several steps that should be followed, the specifics (and dosages) are detailedin Table 1, but in general, the following steps apply to all acute reactions:

- Assure an open airway; provide supplemental oxygen; suction as needed.

- Take pulse and blood pressure.

- Obtain IV access.

- Elevate legs.

- Provide medications, drug box and CODE cart.

- Monitor heart and pulse oximeter.

Actions and treatments

The uncomfortable patient

This patient is experiencing a cutaneous reaction with itching and hives. If these are the only manifestations and the patient has no symptoms of airway compromise, and the pulse and blood pressure are normal, it can be either observed or treated symptomatically. Observe for other signs, symptoms and check vital signs. Use an antihistamine for itching that progresses and/or is not well-tolerated by the patient; e.g. diphenhydramine (Table 1).

The calm, poorly responsive patient

This patient is experiencing either hypotension or hypoglycemia. The patient with hypotension is usually pale, cool to the touch, and might have beads of perspiration on their forehead or upper lip. They might be nauseated. Since the patient is already supine, the hypotension is usually more profound when encountered than if the patient were sitting.

Call for assistance. You will likely need to give IV fluids and oxygen or, in the case of hypoglycemia, a bolus of glucose.

For hypotension, determine whether the patient has concurrent bradycardia or has tachycardia.

For hypoglycemia, inquire about any diabetes history, and determine blood pressure and pulse to exclude hypotension.

For hypotension with tachycardia supply oxygen via mask, elevate the legs to 60 degrees to “dump” fluid centrally, and administer IV fluids (normal saline or lactated Ringer’s solution).

For hypotension with bradycardia (vaso-vagal) reaction, note that this hypotension is compounded by vagally-stimulated bradycardia,which prevents normal cardiac compensation for peripheral vasodilation. Supply oxygen via mask, elevate the legs to 60 degrees to “dump”fluid centrally, and administer IV fluids (normal saline or lactated Ringer’s solution).

If the patient remains hypotensive, feels poorly and has bradycardia, it is essential to treat the bradycardia with IV atropine (Table 1).

Anxious, agitated patient

This patient is hypoxic. These patients feel like they are being smothered or drowning. They want to get out of the scanner and off the table.

They are “desperate.” The longer the hypoxia continues, the more difficult treatment becomes. Call for assistance. You will need to give IV fluids, oxygen and medications. The situation might deteriorate rapidly. First, assess whether the patient has trouble getting air in, trouble getting air out, is short of breath, or is just anxious. Look for other signs of edema that will provide a clue as to the status of the patient’s airway.These signs include edema of the eyelids, lips and face. Look for urticaria on the chest and abdomen.Talk to the patient. Do they have a “squeaky” voice, characteristic of laryngeal edema. Are they coughing? Coughing can also be a sign of laryngeal edema. Do they have a history of asthma. Are they oriented or confused due to hypoxia and/or hypotension.

Take their pulse and assess whether they have tachycardia or bradycardia. Obtain pulse oximetry, blood pressure and begin cardiac monitoring.

As to treatment, provide oxygen, obtain IV access and administer IV fluids (saline, lactated Ringer’s) if hypotensive. Elevate the legs if the patient is hypotensive.

Administer medications directed at the specific cause of the symptoms (Table 1). Bronchospasm should receive beta-2 agonist inhaler. Airway edema or laryngeal edema should receive epinephrine. Pulmonary edema should receive furosemide (Lasix®).

Other medications to consider include diphenhydramine (Benadryl®) which has potential side-effects that can adversely affect treatment. It might cause hypotension or it may thicken airway secretions. Therefore, this drug should not be used in the acute treatment of reactions with manifestations other than progressive or poorly tolerated hives. It should not be used initially in patients with airway symptoms or those with falling blood pressure.

Corticosteroids should be added later in the course of treatment. Keep in mind that they have no effect on acute edema. Their use should be to help prevent delayed, recurrent reaction.

Conclusion

Rapid recognition of the signs and presentations of a contrast reaction allows radiology personnel to identify the type of reaction which, in turn, facilitates rapid treatment and reversal of the reaction.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to acknowledge their colleagues in radiology who have contributed to the teaching about contrast reactions and their treatment. They also wish to thank all those who have participated in the many hands-on instructional courses offered about these topics. Special thanks for the contributions of Drs. Michael Bettmann, Richard Cohan, James Ellis, Geoff Ferguson, Bernard King Jr., Karl Krecke,and Bruce McClennan.

REFERENCES

- Lasser EC. Chasing contrast molecules: A 45 year quixotic quest. Acad Radiol. 2004;11:1190-1196.

- Bush WH and Lasser EC. In: Pollack HM, McClellan BL (Eds.). Clinical Urography (2nd Ed.). Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co.; 2000:43-66.

- homsen HS, Morcos SK, Contrast Media Safety Committee of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology. Management of acute adverse reactions to contrast media. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:476-481. Also: www.esur.org/ESUR_Guidelines_New.6.0.html. Ac-cessed November 11, 2009.

- Katayama H, Yamaguchi K, Kozuka T, et al. Adverse reactions to ionic and nonionic contrast media: A report from the Japanese Committee on the Safety of Contrast Media. Radiology. 1990; 175:621-628.

- Krecke KN. Presentation and early recognition of contrast reactions. In: Bush WH, Krecke KN, King BF, Bettmann MA,eds. Radiology Life Support (Rad-LS). London, England:Hodder Headline/Arnold Publishers;1999:22-30.

- Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media of the American College of Radiology. Manual on Contrast Media, Version 5.0. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2004:7-11, 35-39, 45-50. Also: www.acr.org/SecondaryMainMenuCategories/quality_safety/contrast_manual.aspx. Accessed November 11, 2009.

Citation

Recognition and treatment of acute contrast reactions. Appl Radiol.

December 21, 2009