Mesenteric ischemia secondary to superior mesenteric artery (SMA) thrombus

Prepared by Amy P. Oberhelman, MD and Edward Y. Lee, MD, MPH , from the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University Medical Center, St. Louis, MO.

CASE SUMMARY

A 76-year-old woman with a medical history significant for hypertension, diabetes, and multiple cerebral infarcts presented with a 3day history of progressive abdominal pain and tarry stools. Significant examination and laboratory findings included a diffusely tender abdomen, elevated white blood cell count (19,000/µL), and a positive fecal occult blood test. All other examination and laboratory findings were within normal limits.

DIAGNOSIS

Mesenteric ischemia secondary to superior mesenteric artery (SMA) thrombus

IMAGING FINDINGS

An abdominal radiograph on admission revealed slightly distended small bowel loops containing air-fluid levels consistent with early distal small bowel obstruction or focal ileus secondary to an intra-abdominal inflammatory process (not shown).

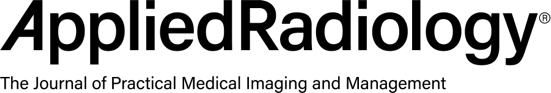

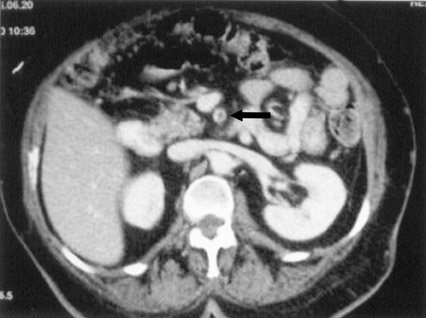

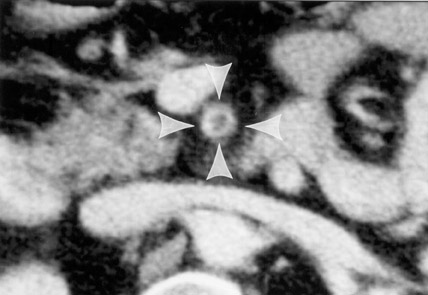

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen showed a partial filling defect of the SMA (Figures 1 and 2). A slight distention of one of the small bowel loops with surrounding mesenteric fat infiltration was also noted, most likely representing ischemic bowel (Figure 3). There was no evidence of pneumatosis intestinalis, portal venous gas, or pneumoperitoneum.

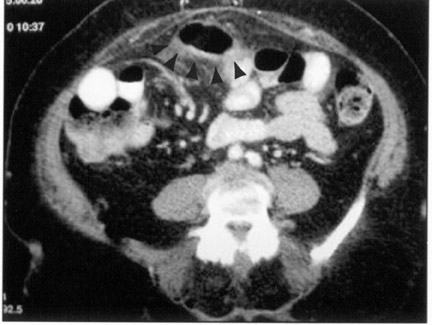

A selective catheter angiogram of the SMA revealed at least three filling defects. The first filling defect, located in the proximal SMA, was nonocclusive (Figure 4). Another nonocclusive filling defect was located in the distal-most branch of the right lower aspect of the SMA. The third filling defect was located in the left aspect of the SMA and was occlusive.

The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy, which revealed nonocclusive thrombus in the proximal SMA. The patient eventually underwent SMA thromboembolectomy and segmental resection and reanastomosis of the distal ileum.

DISCUSSION

Mesenteric ischemia accounts for approximately 0.1% of hospital admissions and is found in 1% of patients with acute abdomen. 1 The nonspecificity of clinical signs and symptoms associated with the early stages of ischemia often delays diagnosis until extensive and irreversible bowel infarction has occurred. These delays in diagnosis substantially contribute to the poor prognosis associated with this disorder, with mortality rates exceeding 60%. 2,3

Mesenteric ischemia most often results from SMA embolization or thrombosis, and, less commonly, venous occlusion or nonocclusive processes. Embo-lization of the SMA accounts for nearly 50% of cases, with thrombosis responsible for another 25% of cases. 4,5 Early identification of the disorder requires a high index of suspicion in patients with significant risk factors, such as congestive heart failure, cardiac dysrythmias, recent myocardial infarction, severe valvular cardiac disease, generalized atherosclerosis, intra-abdominal malignancy, previous arterial emboli, pancreatitis, or hemorrhage. 4,5

In terms of clinical presentation, mesenteric ischemia may present with increasing abdominal pain and decompensation over a period of hours or with symptom progression over several days. Abdom-inal pain is the most common symptom. It occurs in >75% of patients and varies in severity, nature, and location. 5 Pain is often associated with vomiting, diarrhea, diaphoresis, and fever. 6 Unfortunately, despite these symptoms, clinical examination of the abdomen is often benign. Evidence of generalized or localized peritonitis may not be evident until infarction has occurred. Other late signs include hematochezia, hematoemesis, positive fecal occult blood testing, massive abdominal distention, back pain, hypotension, and shock. 5 Leukocytosis (>15,000 cells/µL) occurs in approximately 75% of patients, and more than half of patients will present with metabolic acidemia. 5

Findings on plain abdominal radiographs are normal or nonspecific in >25% of cases of early mesenteric ischemia. 4,5 Subtle signs include adynamic ileus, distended and air-filled loops of bowel, small intestine "thumb-printing," and bowel-wall thickening from submucosal edema or hemorrhage. 5 Advanced stages of ischemia are associated with pneumatosis of the bowel wall and evidence of portal vein gas. 4 CT can be used to detect ischemic changes, such as circumferential bowel-wall thickening, mesenteric stranding of fluid, pneumatosis, and submucosal hemorrhage, or edema. 2 CT may also determine the cause of the ischemia by allowing evaluation of the mesenteric vasculature for embolus, thrombus, atherosclerosis, vasoconstriction, compression, trauma, or invasion by tumor. 2

The definitive diagnostic study for mesenteric ischemia is angiography. Approximately 90% of patients with acute mesenteric ischemia who undergo angiography before the onset of peritoneal signs survive, demonstrating the value of angiography and early diagnosis. 5 In cases of SMA embolization, the classic "meniscus sign" is often visualized at the point of occlusion. Most emboli lodge 3 to 10 cm into the tapered segment of the SMA. 5 Thrombosis is most often identified with a flush aortogram. Although complete occlusion of the SMA usually occurs within 1 to 2 cm of its origin, collateral pathways almost always fill the vessel distal to the obstruction. 5

In terms of treatment, small peripheral lesions may not require immediate surgery and may respond to medical therapy. 3 Anticoagulation is advocated in patients suspected of having SMA thrombosis, and thrombolytic therapy may benefit selected patients with early diagnosis of SMA embolus unassociated with bowel necrosis. 4 In most cases, surgical exploration is emergently performed to restore intestinal arterial flow and resect irreparably damaged bowel.

CONCLUSION

Due to the nonspecific clinical signs and symptoms of the early states of mesenteric ischemia secondary to superior mesenteric artery thrombus, the correct diagnosis is often delayed until extensive and irreversible bowel infarction has occurred. Early diagnosis with CT and angiography can help to make an early diagnosis and to decrease the morbidity and mortality associated with this disorder.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr. Huy Tran, St. Vincent's Doctor's Hospital, Little Rock, AR and Dr. Michael D. Darcy, Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University Medical Center, St. Louis, MO for supplying the images in this report.