Breast screening's trade-offs

As radiologists evaluate the growing number of new breast screening technologies at their disposal, they are becoming increasingly aware that effective screening depends on several factors that go beyond a technology’s ability to detect cancer.

Screening mammography remains the only imaging modality proven to decrease breast cancer mortality in the general population, yet it is not always able to detect all cancers. Over the last few years, the arsenal of breast screening tools has expanded to include breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); molecular breast imaging (MBI), or breast-specific gamma imaging (BSGI); positron emission mammography (PEM); and, more recently, tomosynthesis. The challenge lies in determining which of these screening tools to use in a given circumstance. Some key factors to consider when evaluating each system include its number of false positive findings, which can lead to additional evaluation and often to benign biopsies, as wellas the availability of the equipment, workflow, and cost-effectiveness.

With any breast-screening tool, there are always trade-offs. Take, for example, screening with mammography alone versus screening with mammography and ultrasound. The trade-offs between sensitivity and false positives have been well documented in the American College ofRadiology Imaging Network National Breast Ultrasound Trial (ACRIN 6666). In the study, researchers discovered that adding a single screening ultrasound to mammography yields an additional 1.1 to 7.2 cancers per 1,000 high-risk women; however, they also found that adding ultrasound substantially increased the number of false positives.

“With anything you add to mammography, whether it is MRI or ultrasound, you are going to end up doing unnecessary biopsies,” said Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD, a Diagnostic Radiologist, specializing in breast imaging, and a Visiting Professor, Magee-Women’s Hospital, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. “That is true of any technology, but it’s particularly true of ultrasound. We now know from the ACRIN 6666ultrasound screening trial that after 3 years of getting ultrasound plus screening mammography, we had a very low rate of interval cancers. If we don’t do the ultrasound, that number [ranges from] 30% to as much as 50% in a woman who has dense breasts.”

The promise of tomosynthesis

If screening is going to make a difference in cancer, clinicians need to detect cancer before it spreads to the lymph nodes, stressed Dr.Berg.

“We are much more interested in finding invasive cancer than ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), which is still inside the ducts,” said Berg. “With tomosynthesis, we see masses slightly better, but there appears to be a reduction in sensitivity for malignant calcifications. On average, we may only gain about 10% to12% in cancer detection with tomosynthesis.” However, she noted, more research on tomosynthesis remains to be done.

Breast tomosynthesis is a technique in which 3-dimensional mammographic images of the compressed breast are acquired from multiple angles. The individual images are then reconstructed into a series of thin, high-resolution slices displayed either individually or in a dynamic cine mode. Reconstructed tomosynthesis slices reduce or eliminate problems caused by tissue overlap and structure noise in single-slice,2-dimensional mammography.

The promise of tomosynthesis is that it may improve cancer detection, reduce recall rates, and enable better classification of normal and cancer cases. One of the primary research sites for breast tomosynthesis, the University Hospital Lapeyronie of Montpellier, a teaching hospital in France, uses tomosynthesis as an adjunct to mammography (Figure 1). As Professor Patrice Taourel, Head of the Radiology Department, explains, “Tomosynthesis supplements mammography. We use it on a systematic basis for patients who need more detailed views.”

Over the past year, radiologists at CDB-Premium, Centro de Diagnosticos, a large diagnostic imaging center based in Sao Paulo, Brazil, began using the technique in combination with mammography. They have since discovered that there are many cancers that they have only been able to detect on tomosynthesis. They also say tomosynthesis provides better characterization of most of the lesions, leading to more accurate treatment planning.

Professor Taourel thinks MRI is still the best modality for breast imaging, but he emphasizes it is not necessary or practical in all cases.

“Tomosynthesis can be used easily for patients,” he said. “It takes less time and can be used at the first point of contact with a patient.”

Breast MRI takes on specificity

While alternative methods such as breast ultrasound and tomosynthesis may detect some cancers that cannot be seen by mammography,dynamic contrast-enhanced breast MRI is very sensitive and specific. Breast MRI has been shown to detect more small-node negative cancers in women at high risk for breast cancer, and proven to be a useful screening adjunct to mammography in high-risk women.1

While one of the main attributes of breast MRI is its negative predictive value, overlap in the appearance of some benign and malignant diseases limits the modality’s specificity. This may lead to false-positive findings, resulting in additional evaluations of and/or biopsies on ultimately benign lesions.

Recent advances in technology for dedicated breast-MRI systems aim to overcome the hurdle with specificity. A dedicated breast MRI system, Aurora 1.5T Dedicated Breast MRI System, utilizes Edge technology, which is designed to improve resolution by oversampling in3 planes to avoid artifacts from other parts of the body.

Steven E. Harms, MD, FACR, Professor of Radiology at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock, AR, and staff radiologist at Imaging Associates of Northwest Arkansas in Fayetteville, AR, explains that what is unique about the technology is its “ability to characterize DCIS and separate that on the basis of improved anatomy. DCIS can extend over a fairly large area and still be noninvasive. It’s difficult on most MRI systems to separate DCIS from proliferative change that is a benign feature of the breast.”Dr. Harms added, “What separates breast MRI performed on [this] system compared to whole-body MRI systems is the efficiency of spiral and the ability to improve contrast and resolution at the same time.” As a result, said Dr. Harms, the negative predictive value of the dedicated breast MRI scanner is an estimated 98%.

Nuclear medicine puts MRI to the test

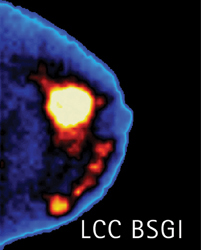

A number of studies have compared breast MRI to nuclear medicine techniques, such as BSGI and PEM. BSGI is a molecular breast imaging technique used as an adjunct to mammography screening (Figure 2). BSGI also has a 98% negative predictive value, said Rachel Brem, MD, director, Breast Imaging and Interventional Center, Professor of Radiology, Vice-Chair, Research and Faculty Development, George Washington University. The modality’s sensitivity to invasive or DCIS is about 94% which, Dr. Brem notes, is comparable to that of MRI.

“For all cancers, BSGI is equal to MRI, except for lobular carcinoma, [where] BSGI’s sensitivity is better than MRI. [However], there are less false positives with BSGI, and that is very important, particularly in premenopausal women,” said Dr. Brem. “In our practice, with women who have multiple enhancing lesions with MRI, we send them to BSGI to help evaluate any of the lesions that are concerning.”

One advantage of BSGI over breast MRI is cost. Dr. Brem points out that both the BSGI equipment and examination are far less expensive than MRI.

“You do not need to wait to inject contrast or check for renal function as is required with MRI,” Dr. Brem indicated. “Fifteen percent of women can’ get gadolinium have an MRI, whether it’s [because of] a cardiac pacemaker, or they are too large to fit in the magnet, or they have renal disease and can’t get gadolinium, or they have severe claustrophobia. But anyone [with] venous access can have BSGI.”

In addition, workflow with BSGI may be more streamlined as radiologists are only required to review 4 to 8 images, compared to having to read up to 1,000 images with MRI.

The downside to BSGI is exposure to radiation from the radiotracer. But, according to Dr. Brem, the technique requires a very low dose.

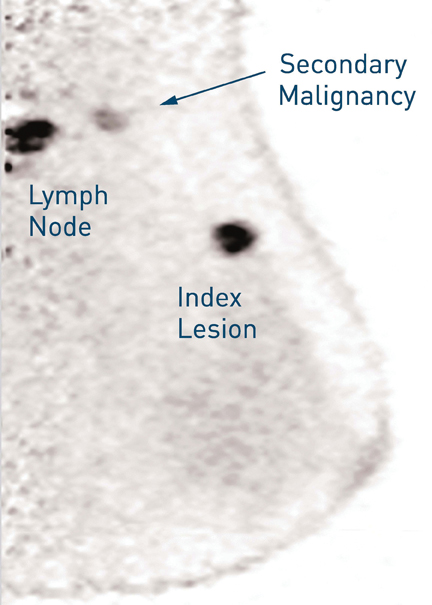

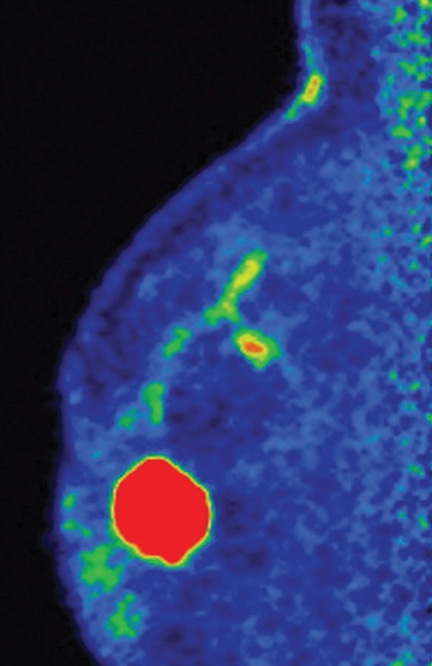

PEM, another nuclear medicine technique for breast screening, is also gaining notoriety (Figure 3). PEM is an optimized positron emission tomography scan designed to provide metabolic visualization of anatomy through tomographic images with resolution as sharp as 2 mm.

In a recent study led by Dr. Berg,2 researchers found that PEM is an acceptable alternative to MRI in women with known breast cancer.

Both PEM and MRI showed greater detail than breast ultrasound or mammogram, which Dr. Berg had expected. However, said Dr. Berg,“There were altogether 82 women in our study who had more cancer than we thought when they entered the study. Of those women, in a third of them…extra cancers were seen on both MRI and PEM, 26% were seen only on MRI, and 17% were seen only on PEM.”

“PEM and MRI see things differently,” added Dr. Berg, “but they are comparable in terms of detecting cancer. MRI is slightly more sensitive than PEM, but PEM is less likely to cause us to do unnecessary biopsies or surgeries.”

In the study, Dr. Berg found that fewer than half of the suspicious findings on MRI were cancer. “With PEM, we are much less likely to cause trouble, and that makes it more attractive,” she said.

Another convenience of PEM is it enables physicians to perform a needle biopsy directly with the system, and then quickly verify it. “Unlike MRI, we are able to prove that we have gotten the right spot,” Dr. Berg said. “If we didn’t for some reason, we can immediately resample at that time, and we can even image the biopsied pieces to make sure they are ‘hot.”

“With MRI, on the other hand, once we have done some sampling, there is often some bleeding, which also looks bright on the image,and we have trouble seeing the lesion we were trying to biopsy. If we have missed, you often don’t know it at the time,” Dr. Berg added.

The development of additional clinical applications for BSGI and PEM may become a decisive factor in choosing the most appropriate technology for patients. With nuclear medicine’s unique ability to measure metabolic activity, both BSGI and PEM may be helpful for patients contemplating chemotherapy prior to surgery.

“BSGI is metabolic, functional imaging,” Dr. Brem points out. “We are increasingly using it to look at response to chemotherapy in women who are getting neoadjuvant chemotherapy.”

While Dr. Berg agrees nuclear medicine is a promising technique for tracking response to chemotherapy, she stresses more research is needed. “We know from the whole-body PET literature it is possible that we can see a change in the tumor very quickly after starting treatment — in as little as 8 days after the chemotherapy was given. If it is not responding, there might be an opportunity to change the treatment.That kind of change may be easier to see more quickly with PEM than with MRI.

While Dr. Berg believes there are a lot of cases in which PEM is just simpler than with MRI, she acknowledges that the technique “does re

quire that the patient not have diabetes because we are injecting a [glucose-based contrast agent], and women have to be fasting for at least 4 and preferably 6 hours prior to the PEM study.”

She also noted that PEM is slightly less sensitive than MRI. “We need to be selective about either test we do, but I think PEM can be a good alternative,” said Dr. Berg “Certainly, PEM seems to be a good option to do instead of MRI for checking pre- and post-treatment.”

With each of these new approaches to breast cancer detection, there is always a trade-off, whether it is sensitivity that’s too high or specificity that’s too low. While it is still unclear which technology is the most effective adjunct to mammography, Dr. Berg sees a clear advantage to having a growing arsenal of breast screening tools.

“Having an alternative before women are treated for breast cancer is [what is] important,” she said.

REFERENCES

- Giovanni DB, Cecchini S, Grassetti L, et al. Comparative study of breast implant rupture using mammography, sonography and magnetic resonance imaging: Correlation with surgical findings. Breast J. 2008;14:532-537.

- Berg, WA, Madsen KS, Schilling K, et al. Breast cancer: Comparative effectiveness of positron emission mammography and MR imaging in presurgical planning for the ipsilateral breast. Radiology. 2011;258:59-72.