Boerhaave's syndrome

Images

Summary: A 51-year-old woman presented to our emergency room with acute onset of left shoulder and epigastric pain. The pain followed an episode of choking and retching during a dinner at a steakhouse. On physical exam her abdomen was tender to palpation most notably in the upper quadrants where she had guarding and rebound tenderness. Laboratory values were unremarkable.

Findings

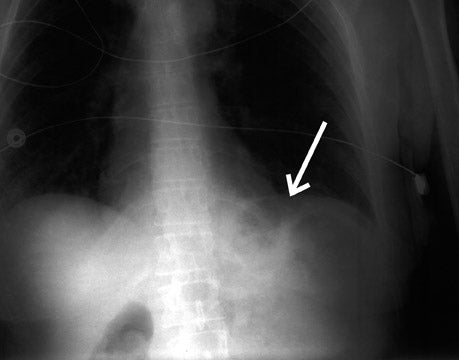

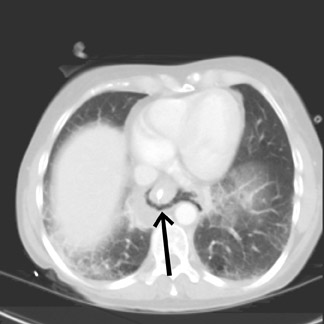

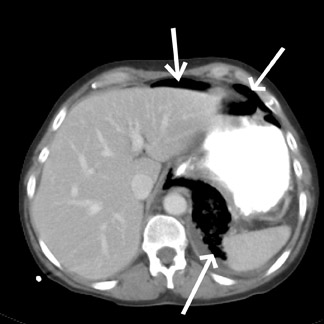

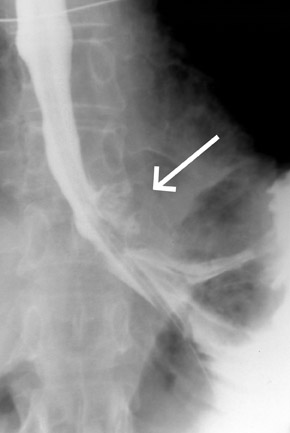

A chest X-ray (Figure 1) showed free air adjacent to the stomach bubble in the left upper quadrant. A computed tomography (CT) scan (Figures 2 and 3) of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, using intravenous and oral contrast, showed mediastinal air adjacent to the descending aorta. The CT scan also showed free intraperitoneal air and a soft-tissue density adjacent to the distal esophagus (Figure 4). No contrast extravasation was seen on CT. Subsequently, barium swallow showed an area of contrast extravasation from the distal esophagus 2.0 cm proximal to the gastroesophageal junction (Figure 5).

Discussion

The patient was taken to the operating room where a 3 cm distal esophageal perforation was repaired via a thoracotomy. A piece of brown tissue was removed from the mediastinum and sent to pathology where it was found to be skeletal muscle consistent with the piece of steak the patient reported ingesting prior to the episode of vomiting. The patient had an uncomplicated hospital course. Upper GI examination 1 week post esophageal repair showed no evidence of extravasation or stricture formation. The patient was seen for routine screening mammography 2 years later and was asymptomatic.

Boerhaave’s syndrome was originally described by Hermann Boerhaave in 1724. The first report was the case of Baron Jan van Wassenaer, High Admiral of the Dutch Fleet, who had severe left-sided chest pain after vomiting. He died 18 hours later and autopsy showed a tear in the distal esophagus, emphysema and food in the mediastinum.1

Esophageal rupture is likely secondary to a rapid rise in the intraluminal pressure of the distal esophagus during emesis.2

The syndrome can be a challenge for clinicians because the clinical presentation rarely has the classic presentation of retrosternal chest pain following an episode of emesis with associated emphysema. Patients may have symptoms that can mimic myocardial infarction, sepsis, pancreatitis or aortic dissection. Additionally, the patients may present with hypotension and shock secondary to mediastinitis. If there is a delay in diagnosis, the morbidity and mortality significantly increase.3

Radiographs may show pleural effusions, pulmonary infiltrates, and/or mediastinal emphysema, usually in the left chest, but can be normal in ≤10% of cases.4

While frequently used as a screening examination, radiographs are often nonspecific for Boerhaave’s syndrome. CT of the chest with intravenous and oral contrast provides greater diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. The most specific findings on CT include air around the distal esophagus and aorta, pleural effusions, esophageal wall thickening and pulmonary infiltrates.4

A fluoroscopic esophagram performed with water soluble contrast is the diagnostic procedure of choice in patients with suspected perforation of the esophagus. Dilute barium can be used if the water soluble contrast is not diagnostic.5 Findings on esophagram that are indicative of perforation include direct visualization of the submucosal tear or extravasation of contrast.4 While visualization of the fistula or the actual tear is a definitive finding, there has been a ≤10% false-negative rate reported with esophagography.6 Helical CT esophagography using oral solution composed of 10% IV iodinated contrast material, effervescent granules and water has shown promising results for demonstrating esophageal extravasation.7

The treatment of choice consists of emergent primary surgical repair of the esophageal tear and removal of debris from the mediastinum. Potential future therapies include endoscopically placed temporary esophageal wall stents in conjunction with mediastinal drainage. These techniques have shown some success in a limited number of cases.8

Conclusion

Boerhaave’s syndrome is a rare form of esophageal perforation with a potentially complex presentation mimicking a variety of disorders. The prompt radiologic evaluation utilizing plain films, computed tomography and fluoroscopic esophagrams may avert the serious complications associated with a delay in diagnosis and treatment.

- Boerhaave, H. Atrocis, nec descripti prius, morbis historia: Secundum medicae artis leges conscripta. Lugduni Batavorum; Ex Officine Boutesteniana. 1724.

- Patton AS, Lawson DW, Shannon JM, et al. The re-evaluation of Boerhaave’s syndrome. AM J Surg. 1979;137:560-565.

- White CS, Templeton PA, Attar S. Esophageal perforation: CT findings. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1993; 160:767-770.

- Ghanem N, Altehoefer C, Springer O, et al. Radiological findings in Boerhaave’s syndrome. Emerg Radiol. 2003;10:8-13.

- Backer CL, LoCicero J 3rd, Hartz RS, et al. Computed tomography in patients with esophageal perforation. Chest. 1990;98:1078-1080.

- Bladergroen MR, Loew JE, Postlethwait RW. Diagnosis and recommended management of esophageal perforation and rupture. Ann Thorac Surg. 1986;42:235-239.

- Farhan F, Diego RE, Samuel DK, et al. Helical CT esophagography for the evaluation of suspected esophageal perforation or rupture. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2004;182:1177-1179.

- Eubanks PJ, Hu E, Nguyen D, et al. Case of Boerhaave’s syndrome successfully treated with a self-expandable metallic stent. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:780–783.