Radiological Case: Intravenous leiomyomatosis

CASE SUMMARY

A 55-year-old woman with a history of stage IA, well-differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma and extensive uterine leiomyomas for which she had undergone total abdominal hysterectomy five years earlier presented to the emergency department with tachycardia,chest pain, shortness of breath, episodic hemoptysis, and bilateral lower extremity edema. On imaging, she had bilateral, lower-extremity, deep venous thrombosis and bilateral pulmonary emboli. She was also found to have pelvic lymphadenopathy, masses in the uterine resection bed, and a mass within the inferior vena cava (IVC) that extended into the right atrium.

IMAGING FINDINGS

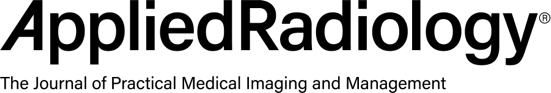

A contrast-enhanced CT scan in the arterial phase revealed multiple heterogeneously enhancing soft-tissue masses in the uterine resection bed, with some of the masses extending into adjacent vessels. An axial image from the same CT scan at the level of the kidneys showed a large, heterogeneously enhancing mass dilating the IVC. A coronal reformatted image also from the same scan showed the mass invading and dilating the infra-renal IVC and extending to the right atrium.

DIAGNOSIS

Intravenous leiomyomatosis (IVL) with intracardiac extension

DISCUSSION

Intravenous leiomyomatosis typically occurs at a mean age of 45 years, and up to 60% of patients have had a prior hysterectomy for uterine leiomyomas, as in the case presented.1,2 Based on reported cases, clinical presentations can be quite variable. Although the condition may be discovered incidentally in asymptomatic patients, most patients present with shortness of breath, tachycardia, palpitations,syncope, abdominal pain and distention, and/or lower extremity edema.1,2 In the case presented, IVL was initially discovered incidentally on pathologic examination of the resected uterus and adjacent vasculature, and knowledge of this history aided the prospective diagnosis of IVL recurrence. This patient was initially asymptomatic, but she later exhibited signs and symptoms of heart failure, presumably from intracardiac extension. Bilateral pulmonary emboli were also diagnosed. Though the association between IVL and pulmonary emboli has been reported, it is seen in less than 5 percent of cases.3 In this case, the pulmonary emboli may have been secondary to bland thromboembolism and/or embolic IVL.

The diagnosis of IVL requires a high clinical suspicion in combination with imaging findings. Fewer than 300 cases have been reported in the medical literature, with about 100 cases reported with direct intracardiac tumor extension.4 The true prevalence of IVLis likely underestimated, as it is frequently misdiagnosed or unrecognized in its early stages. While echocardiography may be helpful in cases with intracardiac extension, contrast-enhanced CT and CT angiography with post-processing can help determine tumor extent, which is especially useful in pre-surgical planning.1,4,5 The typical CT appearance of the mass following intravenous contrast administration can range from hypo- to hyper-attenuating, depending upon the phase of imaging and inherent tumor vascularity.6 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be of added benefit in lesion detection, localization, characterization, and helping to define extent,given its higher soft-tissue contrast resolution and ability to assess blood flow without ionizing radiation.4 A combination of clinical and imaging findings helps to delineate IVL from other diagnostic considerations despite its varying appearance on conventional imaging.On contrast-enhanced imaging, bland thrombus would not show enhancement, whereas tumor thrombus would be expected to enhance and would be associated with a primary malignancy. The differential diagnosis of enhancing intravascular masses would also include leiomyosarcomas. While differentiating these entities from IVL would be difficult, sarcomas tend to be more aggressive and generally invade and extend from vessel walls.

Intravenous leiomyomatosis is a rare neoplasm characterized by benign smooth-muscle proliferation within veins, typically without mural invasion, and is thought to be due to direct extension or growth of a uterine leiomyoma within or into the intima of pelvic veins.5

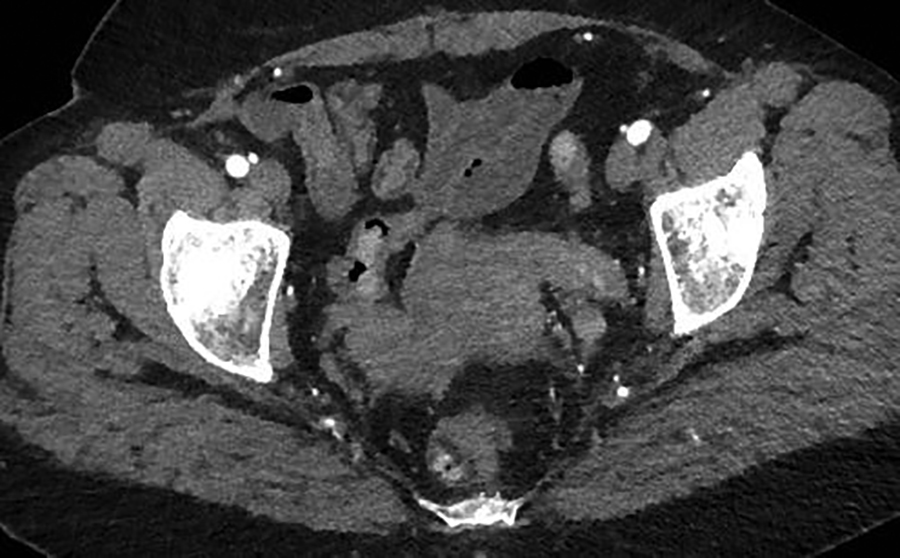

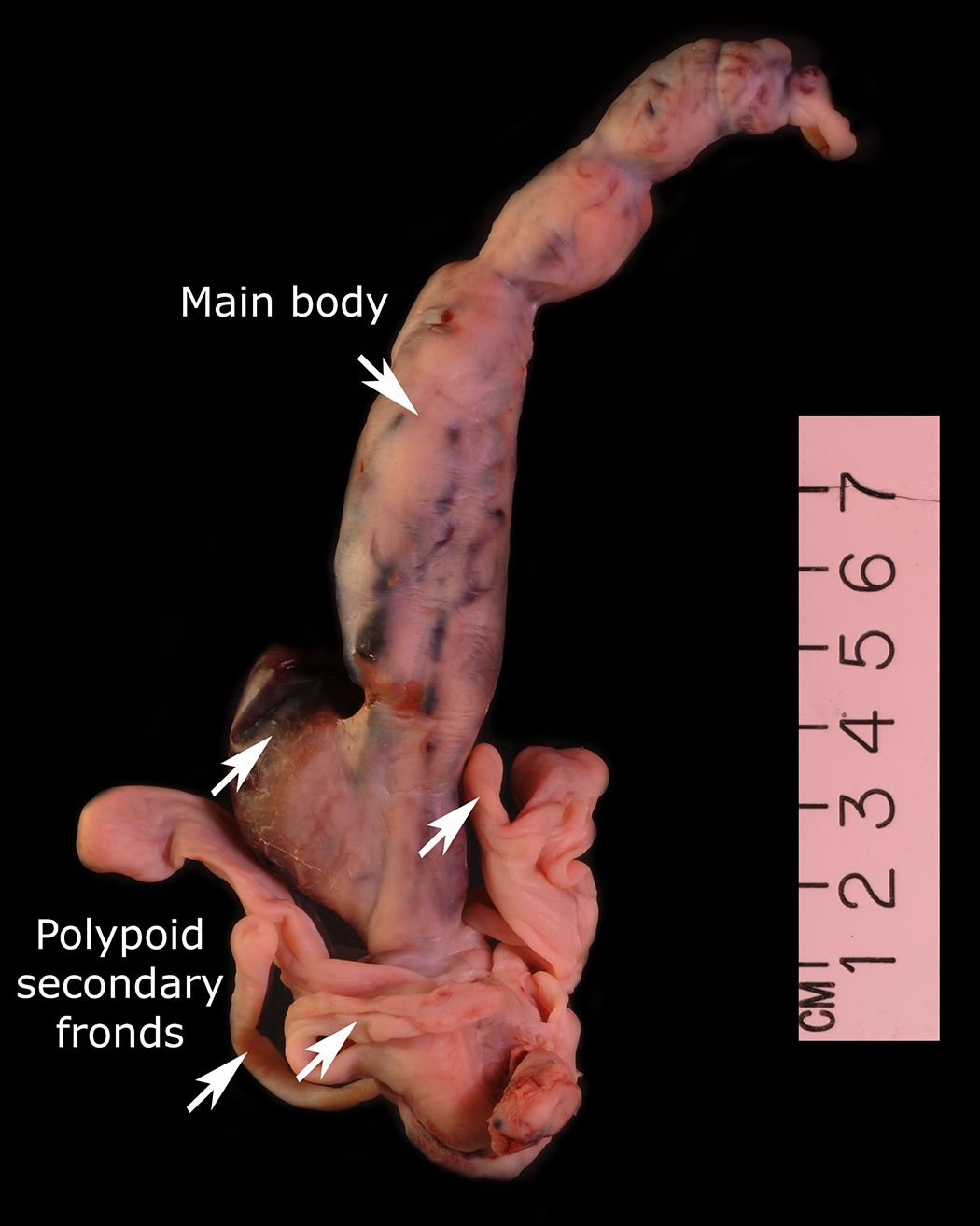

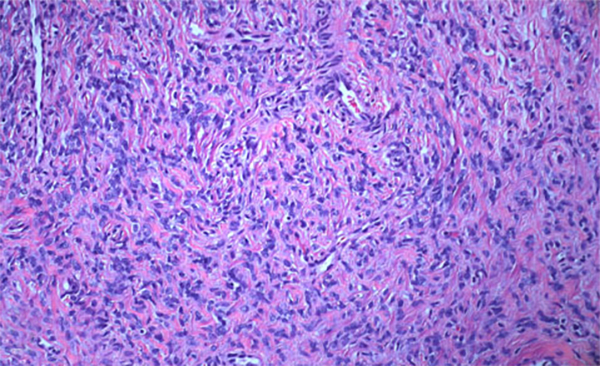

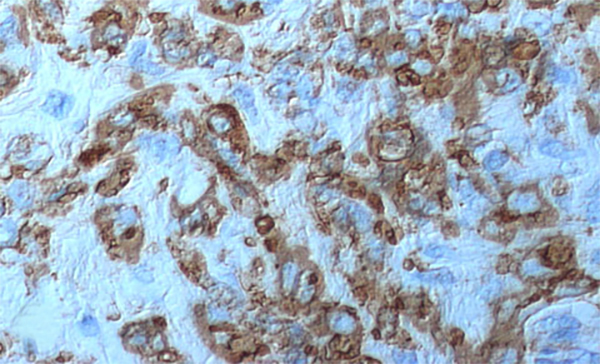

The condition has been reported initially to affect small venous channels within the myometrium and broad ligament, and then enter the systemic venous circulation via the uterine or ovarian veins.2,5 In the case presented, the mass was found to extend into small pelvic veins and the IVC. At surgery, the mass was not adhered to the vessel wall and was easily stripped using traction. Figure 4 shows the gross specimen status post-excision as a 19 × 1.5 cm, grey-white mass with multiple elongated, polypoid secondary fronds. The mass was composed of histologically benign smooth-muscle cells with prominent vascularization by arterial and venous supply, as is typical for IVL (Figures 5A and 5B). Immunohistochemical staining shows staining of the tumor cells with smooth muscle actin in the cytoplasm (Figure 5C). In addition, the nuclei of the tumor cells show abundant expression of progesterone receptors (Figure 5D).

The mainstay of IVL management is complete excision of the tumor, including total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingooophorectomy to prevent the stimulatory effects of estrogen, as was performed in this case. Depending on preoperative suspicion and an accurate assessment of tumor extent, a multidisciplinary surgical team or a two-stage surgical approach may be necessary. The utility of anti-hormonal therapies, such as tamoxifen or GnRH agonists, as neoadjuvant therapy or primary therapy in patients who are not surgical candidates, is controversial.1 Despite presumed complete excision, recurrence rates have been reported to be as high as 30%, and routine surveillance imaging is recommended, though there is a lack of consensus as to the timing of such follow-up.7

CONCLUSION

Intravenous leiomyomatosis is a rare, benign, smooth-muscle neoplasm with a spectrum of clinical presentations. It can be isolated to the peritoneal cavity or it can present with an extensive intravenous mass with extension to the right atrium. Subsequently, patients maybe asymptomatic with IVL detected incidentally, or they may present with symptoms ranging from shortness of breath to heart failure or sudden death. Diagnosing IVL requires high clinical suspicion and correlation with contrast-enhanced cross-sectional imaging. Typically, complete surgical excision of the tumor is required and may be combined with neoadjuvant hormonal therapy to counter estrogenic stimulatory effects. Despite adequate local tumor resection, recurrence is common.

REFERENCES

- Clay TD, Dimitriou J, McNally OM, Russell PA, et al. Intravenous leiomyomatosis with intracardiac extension - a review of diagnosis and management with an illustrative case. Surg Oncol. 2013 Sep;22(3):e44-52.

- Lam PM, Lo KW, Yu MY, Wong WS, et al. Intravenous leiomyomatosis: two cases with different routes of tumor extension. J Vasc Surg. 2004 Feb;39(2):465-9.

- Ribeiro V, Almeida J, Madureira AJ, Lopez E, et al. Intracardiac leiomyomatosis complicated by pulmonary embolism: A multimodality imaging case of a rare entity. Can J Cardiol. 2013;(12):1743.e1-3.

- Xu ZF, Yong F, Chen YY, Pan AZ. Uterine intravenous leiomyomatosis with cardiac extension: Imaging characteristics and literature review. World J Clin Oncol. 2013;4 (1):25-28.

- Low G, Rouget AC, Crawley C. Case 188: Intravenous leiomyomatosis with intracaval and intracardiac involvement. Radiology. 2012; 265(3):971-975.

- Bilyeu SP, Bilyeu JD, Parthasarathy R. Intravenous lipoleiomyomatosis. Clin Imaging. 2006;30(5):361-364.

- Wang J, Yang J, Huang H, Li Y, et al. Management of intravenous leiomyomatosis with intracaval and intracardiac extension. Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 120(6):1400-1406.